In early 2021, there were challenges in managing immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border, with an increase in the number of migrants, particularly unaccompanied children, arriving in the U.S. This situation strained resources and led to debates over immigration policy and border security.

According to data shared by Border Patrol, the number of migrant apprehensions since October 1999 had never exceeded 225,000 in a single month until last year. In 2023, U.S. Border Patrol agents took into custody more than 225,000 migrants who crossed the southern border—in between official crossings—during the first 27 days of December (this number does not include approximately 50,000 more migrants who come each month to ports of entry usually with appointments). The recent influx of migrants at the southwestern border has been a critical topic of discussion between the U.S. President Joe Biden and his Mexican counterpart, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, as they work to address these issues through diplomatic efforts and domestic policy changes.

Laura Sanchez, a Mexican-American journalist, shares her upbringing straddling the border of two nations. She deftly expands the dialogue by engaging six fellow creatives whose artistic expressions are similarly shaped by their bicultural backgrounds. Through their collective voices, the ceaseless cross-border movement is humanized, transcending statistics and evolving into an inspiring portrayal of individuals seeking to embrace their identities.

On most Saturday evenings, while growing up, my dad, uncles, and their friends would drink beer and blast corridos from my dad’s truck outside, while the women sat inside, catching up on the latest family updates, you know, chismeando, and watching TV. And the kids—somewhere running around way past dark. Saturdays were for carne asadas, Modelos and too much junk food. When the beers kicked in, the men would migrate back inside and play their favorite rancheras while we all laughed at their humorous attempts to follow along. The nights were long and full of life. Sundays were for birria and lounging around until traffic somewhat abated, and it was time to drive back home—how we dreaded that weekly journey.

Thousands of cars line up daily at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, the largest land border crossing between San Diego and Tijuana, all waiting to do the same thing we were doing—return home to San Diego for work and school on Monday. It’s been about five years since I last crossed the border, but I can still hear vendors’ incessant honking and shouting. The vendors with their religious trinkets and fruit doused in chamoy and Tajin, the acrobatic street performers, singers, and those with impressive yet dangerous spit-firing skills. But no matter the distractions, the crossing was always long and exhausting. Sometimes my dad would chase lanes that were moving faster. He would cut cars and yell back at other drivers (I’m sure he still does). In a way, it made the wait a little more exciting.

The Mexico-U.S. borders are mere geographical demarcations. They represent cultural and social intersections marked by shared histories, economies, and familial ties. The heightened security measures established by the U.S. government in these zones often manifest as barriers, both physical, like walls, and procedural, like stringent customs and immigration checks. Paradoxically, such rigorous measures have hindered movement and incited waves of rebellion and bursts of creativity throughout the years.

I often look back at that time in my life, as a kid, when crossing the border was just a boring trip back home to San Diego, not nearly understanding the political and social tensions that affect millions of families today, including mine. As I got older and started crossing to Tijuana to frequent bars and go to local shows, I began to understand how both sides of the border have maintained connections for generations, even when increased security feels like an abrupt dislocation. But far from being mere points of division, these cities and their interwoven fates remind us of our drive to connect, express, and evolve.

When I moved to New York City, I met other creatives who, like me, had grown up in a border town. I spoke to six of them living across different cities about their experiences and how the cross-border flow of culture and ideas has influenced their work.

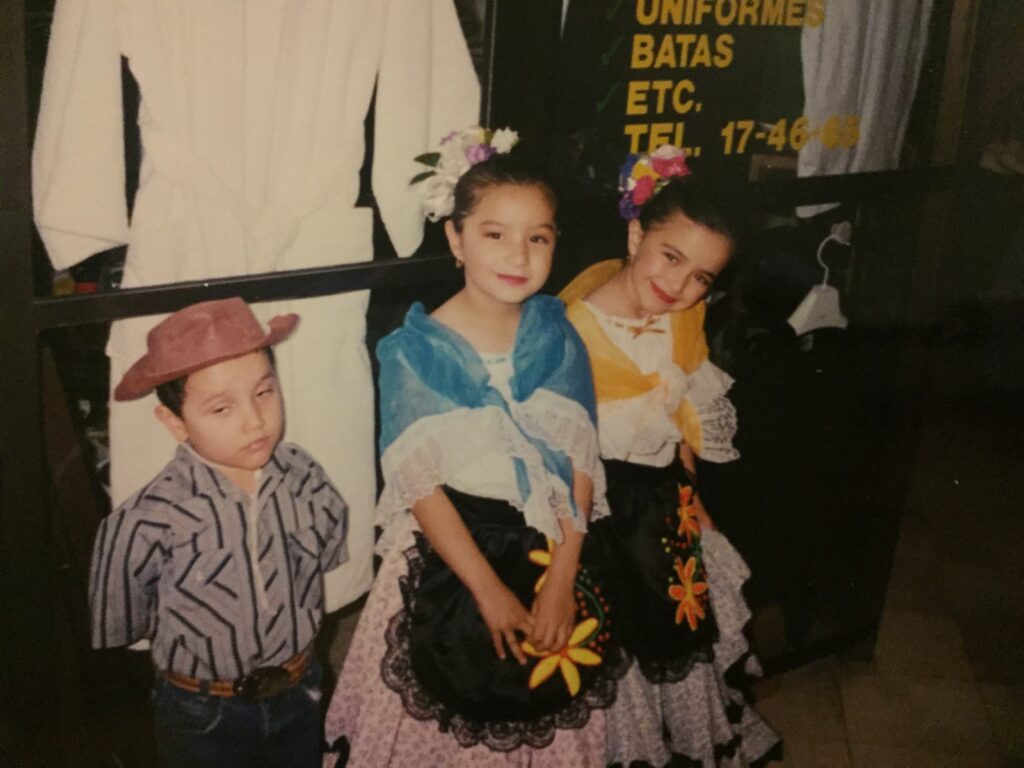

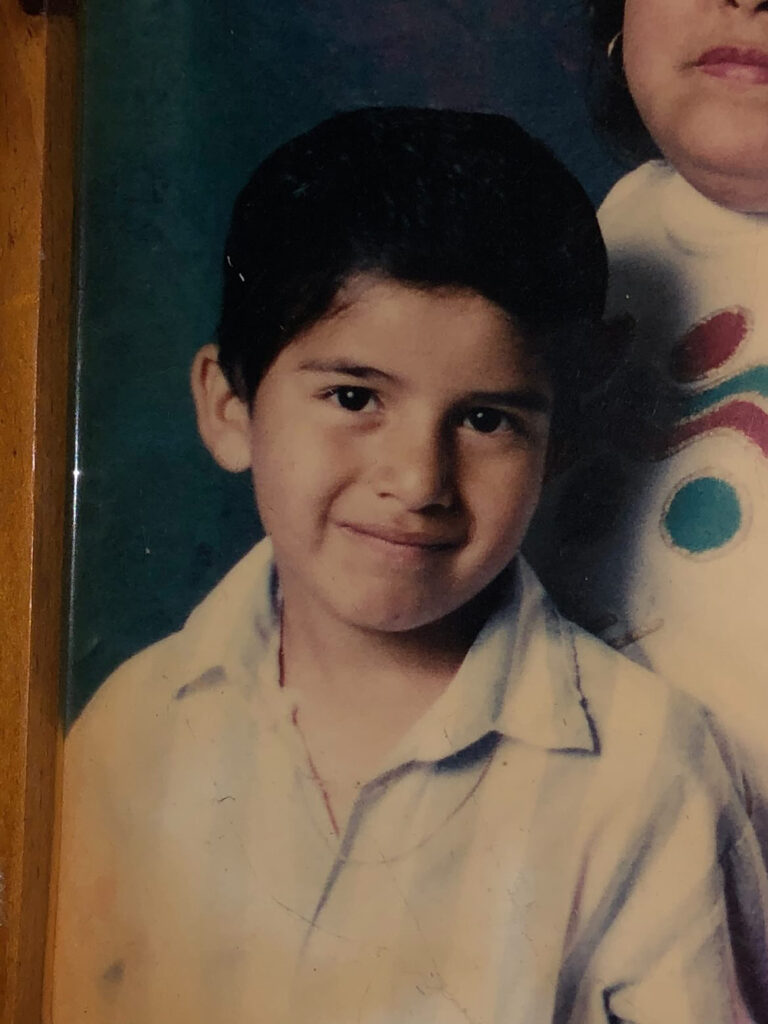

Itzel Alejandra Martinez, Photographer & Ceramicist, Juarez/El Paso

Courtesy of Itzel Alejandra Martinez.

Can you describe a vivid memory from your childhood in El Paso/Juarez that encapsulates the energy and tension of growing up near the border?

My earliest memory of understanding the border and the tension there was when I was six years old, going from Juarez, where I lived most of my childhood, to El Paso, where I went to school and my mom worked. Every school day, for about an hour, we would cross el puente libre with two of my friends who carpooled with us.

I remember my mom playing her usual tapes—Juan Gabriel, Ana Gabriel, and probably Ricardo Arjona; we’d sing along with my two other friends. But this one time was different, customs stopped us. We were separated and searched for what felt like half a day, a K-9 stripped our car, and then once nothing was found, the border patrol gave us some sad little K-9 trading cards to calm us down. To me, this is what it means to grow up in border cities, it’s being in a state of ambivalence, of understanding joy and distress at the same time, a never-ending cycle.

Being raised in a border city, especially with heightened security measures, comes with challenges. How have these challenges shaped your perspective on resilience and rebellion, and how does that perspective manifest in your creations/work?

Before this land was established as Texas or Chihuahua, it was seen as the frontier from the U.S. and Spanish sides. It’s a desert where only a small percentage of the land is suitable for agriculture, you have to be resilient to survive. It’s a place that historically has seen many wars and is currently a highly militarized area. Still, people have not only survived and thrived but, through their resilience, created beauty.

In my photography, I capture people from my border community in a way that reflects their personal and collective pride. Creating those images is crucial since most people outside border communities only see the atrocities. Ceramics, on the other hand, is one of the oldest artistic practices and, because of that, is inherently resilient. Handbuilding ceramics has been a healing journey, inspired by generations of Southwest indigenous potters.

Stories from the border often revolve around themes of separation and unity. Can you share how as a creative you address or challenge these narratives?

In my creative process, I want to understand the role of the imaginary and the intangible. What would an anti-capitalist and anti-border El Paso/Juarez feel like? What would a monument to promote collective grief look like? What would the Rio Grande/Bravo sound like today without border intervention?

“Alameda Dreams” courtesy of Itzel Alejandra Martinez.

Border cities inherently house dichotomies—two countries, cultures, and sometimes contrasting lifestyles. How have these inspired your creative process, and influenced the themes, aesthetics, or styles in your work?

In Juarez, my mom would stop the car to look at beautiful houses and their fountains. She would reflect on the shapes and colors, and dream of having one on our patio. Influenced by her love of fountains, I started creating my own ceramic ones. In them, I merge the geometrical forms of mid-century modern architecture, the silhouettes and coiling method of Casas Grandes’ pottery, the shapes of Talavera fountain bases, the decorative elements of norteño and southwest fashion, and phrases that have lingered in my mind. I see them as small monuments that carry a collection of the countless histories that make up the Texas and Chihuahua region.

Looking forward, how do you aim to further incorporate or evolve the influence of your border city upbringing in your future projects? Are there any untold stories from the border that you are eager to explore or share?

Right now, I’m particularly interested in interviewing and photographing working border artists who have been creating for over 30 years. I’m also looking into the influence of corridos in the border region.

In my ceramic work, I’ve explored collective grief and imagined what that could do for our border communities. Cristina Rivera Garza, a fellow fronteriza and amazing writer, states, “I do not want to avoid suffering. I want to think through and with pain, and too painfully embrace it, to give it back its beating heart with which this country—these countries—still palpitates. Grieving breaks us apart, indeed, and keeps us together.” Fronterizos have not been allowed to grieve, to heal, or even simply to process shock and pain, and the time for that is now.

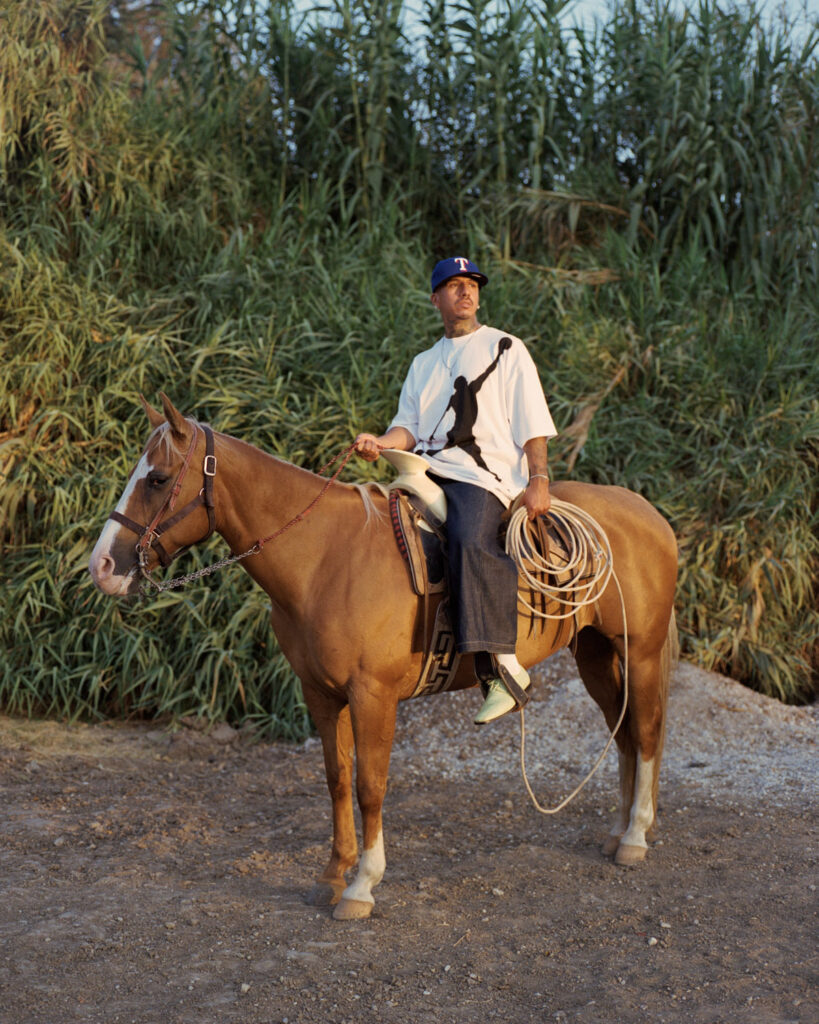

Fabian Guerrero, Photographer, Brownsville/Matamoros

Courtesy of Fabian Guerrero.

Can you describe a vivid memory from your childhood in TX/MX that encapsulates the energy and tension of growing up near the border?

[Every other weekend I would leave] my grandma’s house [in Mexico] and head back across the border [to the US] to see my mother. At the time, those were tense moments. My life as a kid had already been adapted to being in my grandma’s house in Mexico. Since my mom and dad never married, my grandma’s house became my foundation, [and leaving felt like] I was getting taken away from it all, so I think that’s where some of that pain and trauma began. I remember always crying because I didn’t want to leave.

Being raised in a border city has challenges, especially with heightened security measures. How have these challenges shaped your perspective on resilience and rebellion, and how does that perspective manifest in your creations/work?

This is a very long conversation to have. However, the manner in which certain challenges have influenced my perspectives and methods of resistance involves confronting the primary issue in this country: white supremacy. The Republican Party in Texas has been finding more ways to push higher security and life-threatening measures to keep people from crossing. Yet, as someone growing up by the border, you are most likely to get recruited to work for border patrol because historically, poorer communities and brown folks have been easy targets to recruit. This causes our people to go against each other to enforce rules and punishment. I hope the more time I spend here and the more research I do, the more these [tensions] and conversations will be reflected in my work.

Courtesy of Fabian Guerrero.

Stories from the border often revolve around themes of separation and unity. Can you share how as a creative you address or challenge these narratives?

The work I’ve been doing around the border has been shedding light on the communities/people that come from these places, telling their stories of how they navigate, network, build, and create. It’s a matter of building trust, being willing to listen, and being aware of the many situations when it comes to border life. It is not always about trauma; there’s still beauty.

Border cities inherently house dichotomies—two countries, cultures, and sometimes contrasting lifestyles. How have these inspired your creative process and influenced your work’s themes, aesthetics, or styles?

For a long time, these two places, from one side of the border to the other, have developed a unique culture and way, but you get the best of both worlds by the border. For example, a particular way of talking has developed by the border. Cultures clash in ways that tend to stay there. Sometimes, it’s hard to explain, which has inspired me to make work about these places and their people.

Looking forward, how do you aim to further incorporate or evolve the influence of your border city upbringing in your future projects? Are there any untold stories from the border that you are eager to explore or share?

Our histories aren’t included in textbooks. Our stories lie buried deep underground or forgotten, especially in the Texas valley. We should all know these stories to have a deeper understanding and connection to our history. I’m doing my best to highlight the places that were always home, Brownsville, the valley, and across, into Tamaulipas and Monterrey.

Pablo Lara, Coffee Trader, Tijuana/San Diego

Courtesy of Pablo Lara.

Border cities often see a fusion of various practices and tastes. How has this blend of coffee cultures influenced your career as a coffee trader?

The obvious answer is my focus and respect for coffee from Mexico. In the specialty-coffee world, especially ten years ago when I started, Mexico was not known for having the best coffee. Mexican coffee was [often considered a] blender coffee, known for producing high volume, lower grade lots. This has changed in the last eight years or so. [Production of Mexican] high-quality coffee has increased, and the market for Mexican coffee has expanded.

High border security can impact the trade of goods, including coffee. How have you navigated these challenges in your trading practices? Has it forced you to be more creative or innovative in your approach?

Developing that market and changing the paradigm of Mexican coffee has been a driving force in my career. I’ve had the privilege of working with Israel Paz of Denso Coffee, Samuel Ronzon of La Joya, Andreas Kussmaul of ECC, and many others. These people and my trips with them have helped me understand the complexities of buying coffee in these regions, the challenges, and the potential for strong supply chains and delicious coffee.

How does the creative spirit that exists by the border manifest in your coffee trading practices?

Our San Diego and Tijuana border is a cradle for creativity. I’m constantly influenced by local artists like Panca, Itzel Martinez and Georgina Treviño, to name a few. There is a border aesthetic that is very fun and particular. I try to bring that with me by buying fun coffees and fostering collaborations between coffee roasters, artists, breweries, and bakers. And this also led me to do Cold Brew City Fest with Itzel Martinez and Kain Adams. Here, too, the border comes into play by inviting competitors from Ensenada, and Tijuana, and vendors from across the border to create an atmosphere truly representative of our unique border region.

What factors do you think contribute to the unique popularity of Mexican coffee and the emergence of Latino-owned cafes and roasteries?

The SoCal clientele is very unique. Mexican coffee is very popular because we are so near the border, and people feel a familial tie to it. It’s beautiful. I’m witnessing an increase in Latino-owned cafes and roasteries: Iron & Kin, Provecho, Picaresca, and many others inspired by the border, such as Genteel Coffee; people care about Mexican coffee and its development, and are proud to carry it.

Looking ahead, how do you aim to integrate your experiences of growing up in a border city into your future trading endeavors? Are there unexplored markets that you are keen to introduce to a wider audience?

Working with Andreas of ECC and sourcing an anaerobic natural from Chiapas from Victor Ruiz has been a hit in San Diego. Seeing everyone’s take on this coffee called Dragon has been beautiful. I’m very excited to see the collaboration between Itzel Martinez and the Coffee & Tea Collective. The Women’s Coffee from Veracruz, Zongolica Women Power, has also been a hit. Supporting women-grown coffee is very important to me, and I love that so many people support Ultreya Coffee and Nostalgia Coffee, both women-owned coffee companies.

Tania Maldonado, Head Chef, Tijuana & San Diego

Courtesy of Tania Maldonado.

Can you recount a specific memory from your childhood in Tijuana/San Diego that encapsulates the unique flavors and culinary culture of growing up near the border? How has this memory influenced your approach to cooking?

What always reminds me of home is crossing the border and seeing the stands and vendors who walk up to you, offering tacos, burritos, tamales, and other foods. I grew up with that Mexican food and that experience of crossing the border is what captures the unique flavors of my childhood. For me, growing up by the border is tasting homemade food on the streets. So, when I cook, I want people to take a bite of my dish; for example, mole tostadas, and experience my take, as well as the type of food their mother, grandmother, or tia used to cook.

With heightened border security affecting the availability of certain ingredients or limiting cultural exchange, how have these challenges shaped your resourcefulness or creativity in the kitchen?

Getting Mexican ingredients by the border was relatively easy because you typically have access to them on both sides. However, now that I am in New York, it’s harder. Before, if I needed a special ingredient unavailable in San Diego, I would just cross over and get it. When I can’t get a certain ingredient in NYC, the challenge is finding other ingredients I can experiment with to achieve my desired taste.

Courtesy of Tania Maldonado.

How does the rebellious or activist spirit, often seen in border towns, manifest in your culinary choices? Are there dishes you create that aim to make a statement or challenge the status quo?

Well, it doesn’t so much challenge the status quo, but [I aim] to share [my] culture while eliminating certain stereotypes. As a chef at Public Records, I’m very pleased to share my culture at a vegan restaurant. Adapting certain dishes can sometimes be difficult, but I enjoy the challenge. I try to find new ways of creating dishes that most people might not expect at a vegan restaurant; I want to prove that vegan food can have a lot of flavor, with a taste of my culture.

Living in a border city exposes one to contrasting culinary traditions from both sides. How have these dichotomies inspired your menu choices or the ingredients and techniques you employ?

Growing up in a border town has definitely influenced my interest in fusing my culinary practices. I don’t like to focus only on one type of cuisine. I like to encompass various styles of food from different countries, not solely Mexican. The border exposes you to many different types of fusion food that may sometimes only exist there.

As you look to the future, how do you plan to incorporate your experiences growing up in a border city into your culinary ventures? Are there any untold stories or unexplored flavors from the border that you’re excited to bring into your kitchen?

I try to show Mexican culture in a different and modern version but with that classic touch that reminds you how great it is. I experiment with new ingredients, creating something unique, rich in flavor, and innovative.

Raul Muñoz, DJ & Producer, Juarez/El Paso

Can you describe a vivid memory from your childhood in Juarez/El Paso that encapsulates the energy and tension of growing up near the border?

My mom, brother, and I would drive to Ciudad Juarez to stay with my dad on weekends. Before getting on the bridge lane, my mom would park at any light on the main road headed to the tollways. It was an unspoken bus stop where commuters with big vehicles, like my mom’s truck, would take extra people across the bridge. I remember it was mostly elders and sometimes whole families. My mom would roll down my window in the front seat and offer them a ride back to Ciudad Juarez. It was a small gesture, but it meant so much to my mom and the people at the light. She did it every time. There is still so much lacking in human connection and empathy, especially in a place as unique and fragile as the El Paso and Ciudad Juarez border. It’s important to show kindness when you can.

Being raised in a border city comes with challenges, especially with heightened security measures. How have these challenges shaped your perspective on resilience and rebellion, and how does that perspective manifest in your creations/work?

Even in a border city, with so much culture framing the narrative, colonization [still exists], repackaged and sold to the masses. Some people are told different stories of how a city grows and why certain neighborhoods get erased. It’s important to fight for your neighborhood, your community, and your history. Resistance comes in different ways but starts with loving yourself and your gente.

Stories from the border often revolve around themes of separation and unity. Can you share how as a creative you address or challenge these narratives?

I feel like Chicanos sense a separation from their ancestors and their heritage as they become more in touch with their feelings and see a bigger picture for themselves. Not every person fits into the same box as past generations. While we separate ourselves from the past, though it’s painful, we go through a metamorphosis that sheds the necessary and binds us to the love displaced in our history and culture.

Border cities inherently house dichotomies—two countries, cultures, and sometimes contrasting lifestyles. How have these inspired your creative process and influenced your work’s themes, aesthetics or styles?

Growing up with two cultures, they constantly compete for your attention, growth, and love. As we get older, and our Spanish worsens, we cement some ideas and bury others. I’m more open now to my past, the cultures, and the sensitivities that groomed me in the borderland. You could say that my work now has a refined flavor that is picoso. I’m working to create my own mold as a Chicano, and I’m trying really hard not to forget my origins.

Looking forward, how do you aim to further incorporate or evolve the influence of your border city upbringing in your future projects? Are there any untold stories from the border that you are eager to explore or share?

I want to visit Texas more and reconnect with the city that brought me up. I was a writer before I started producing and DJing. I had a lot of fun writing short stories and creating worlds in my children’s books. But I was never able to write about my family. All the characters and chisme were there but my pen never had the attention or heart to begin. There is trauma there that has calcified. I hope one day I can get closure and write my damn story.

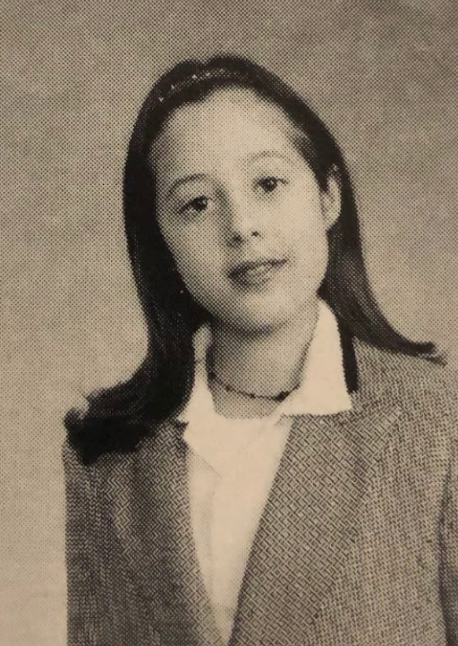

Georgina Treviño, Contemporary Artist & Jeweler, San Diego/Tijuana

Courtesy of Georgina Treviño.

Can you describe a vivid memory from your childhood in Tijuana that encapsulates the energy and tension of growing up near the border?

I have many vivid moments, both positive and negative, but the ones that stuck more are memories that are part of why my parents decided to move to San Diego. Back in the early 2000s, when the narco groups were constantly terrorizing the city, [we had to take a detour to school] because there was a man hanging from a bridge with a narco message. It’s not a great memory to have as a child, but these stories were normalized while living on the border. As you get older, you realize it wasn’t normal for others. It’s that moment when you start understanding the tension and challenges of living by the border.

Being raised in a border city, especially with heightened security measures, comes with challenges. How have these challenges shaped your perspective on resilience and rebellion, and how does that perspective manifest in your creations/work?

Being a fronteriza and living on both sides has made me fearless because I feel I have the liberty and privilege to cross and navigate either side and perhaps that has translated into my work. That fearlessness has made me more resilient, so I don’t mind what people might think about my work. I am very unapologetic when it comes to creating.

Courtesy of Georgina Treviño.

Stories from the border often revolve around themes of separation and unity. Can you share how as a creative you address or challenge these narratives?

I see it as two countries, two cities, but one community separated by a wall. For my most recent work, I was invited to be part of a two-part show called “The Border.” One is in a museum in El Paso, and the other is in a space in Juarez. The concept behind the show was to exhibit one or two pieces per artist, but my idea was to create one piece on either side, which communicates with each other. So I created two flip phones to reference when I lived in Tijuana, during the early 2000s, when I used a Nextel. I incorporated many Y2K motifs from crossing the border, like decals on cars, “tacky” imagery, and objects that remind me of when I lived there. [One flip phone is in either location,] with a number attached to each one so that people can send anonymous messages, selfies, or photos to the other side. Surprisingly, the messages have been very poetic; I hope to document these messages in a book that speaks on those themes of separation and unity.

Border cities inherently house dichotomies—two countries, cultures, and sometimes contrasting lifestyles. How have these inspired your creative process and influenced the themes, aesthetics, or styles in your work?

I’ve been using the 90s and Y2K motifs and typography that we still see crossing the border as an aesthetic and inspiration for my work.

Looking forward, how do you aim to further incorporate or evolve the influence of your border city upbringing in your future projects? Are there any untold stories from the border that you are eager to explore or share?

As I get older, I’m looking back at the bars and venues I grew up frequenting in Tijuana, like Estrella or Tropics, and I want to incorporate elements that reference those places in my work. The idea is to dissect these places and use parts of them for inspiration, like the lighting or colors, because we grew up going there before we were even 21, and now I see them from a different perspective. Sometimes you look outside for inspiration, and when you start to find yourself, you notice the places that were always there and represent where you’re from.

Laura Sanchez is a Mexican-American writer and DJ based in Brooklyn, New York.