Over a Zoom video call from his Los Angeles studio, Joey Terrill confesses, “I want people to know I tried my best.” His humility reflects his commitment to serving his communities. Throughout a career spanning nearly five decades, Terrill has explored the intersection of his Chicanidad and queerness. As an artist, activist, and health educator, Terrill emerged in the ’70s, actively participating in the gay liberation and Chicano movements. At a time when these worlds felt disparate, Terrill worked to bridge the gap between them, tenderly humanizing what it meant to be Chicano and gay and later what it meant to live through the AIDS/HIV crisis and memorialize fallen loved ones. He did so through community-focused work and his art. Through canvas, zines, and mail art, he blends his lived experiences with a DIY ethic, pop-inflected forms, humor, and irreverence.

Born in Los Angeles in 1955, Terrill grew up in the neighborhoods of Lincoln Heights, Highland Park, and Echo Park. From an early age, Terrill was drawn to Mad Magazine, comic strips, and cartoons, despite the characters never resembling him. He attended Cathedral High School, an all-boys school, and later Immaculate Heart College in 1973, home to a renowned printmaking program made famous by Sister Corita Kent. It was there that Terrill trained in the visual legacies of pop art.

Joey Terrill, 2024. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Around the same time, Terrill attended Friday Night Gay Funky Dances at Troupers Hall on La Brea Avenue, south of Hollywood Boulevard. There, he met fellow artists and lifelong collaborators like Mundo Meza, Gronk, and Patssi Valdes. In the glam dance hall miles away from their homes, the seeds for intimate friendships and love were sown. However, Terrill understood the divide between Hollywood and East Los Angeles was more than physical. Hollywood was a predominantly white gay space, while East Los Angeles was shaped by Chicanismo, a movement influenced by heteronormative machismo. In a recent interview for Hyperallergic, Terrill explains, “I was living in two worlds: one in Hollywood and one on the Eastside. And I was determined to confront and blend the two in my art.”

Terrill’s fusion of Chicanidad and queer culture was not bound to a single medium. In 1975, he designed t-shirts emblazoned with the words “dyke” and “faggot” for a demonstration. Marchers formed a visible cadre reclaiming public space and pejorative slurs. The following year, he expanded his concept with a series of t-shirts with the words “malflora” (a Spanish pejorative term for a lesbian meaning “dirty flower”) and “maricón” (the Spanish counterpart to faggot), while the backside read “Rolemodel.” This time, the t-shirts were exclusively worn by the artists and friends known as the Escandalosas as a testament to Chicanx active participation in the emerging gay and lesbian activism of the 1970s. In doing so, Terrill and his collaborators explored the possibilities that self-presentation, adornment, and embodiment could offer. It was Chicanidad within a queer context. Handwritten in an old English Gothic script associated with Cholx culture, Terrill was also addressing machismo and homophobia in Chicano culture. His work in queering the Chicano homeboy aesthetic was just beginning.

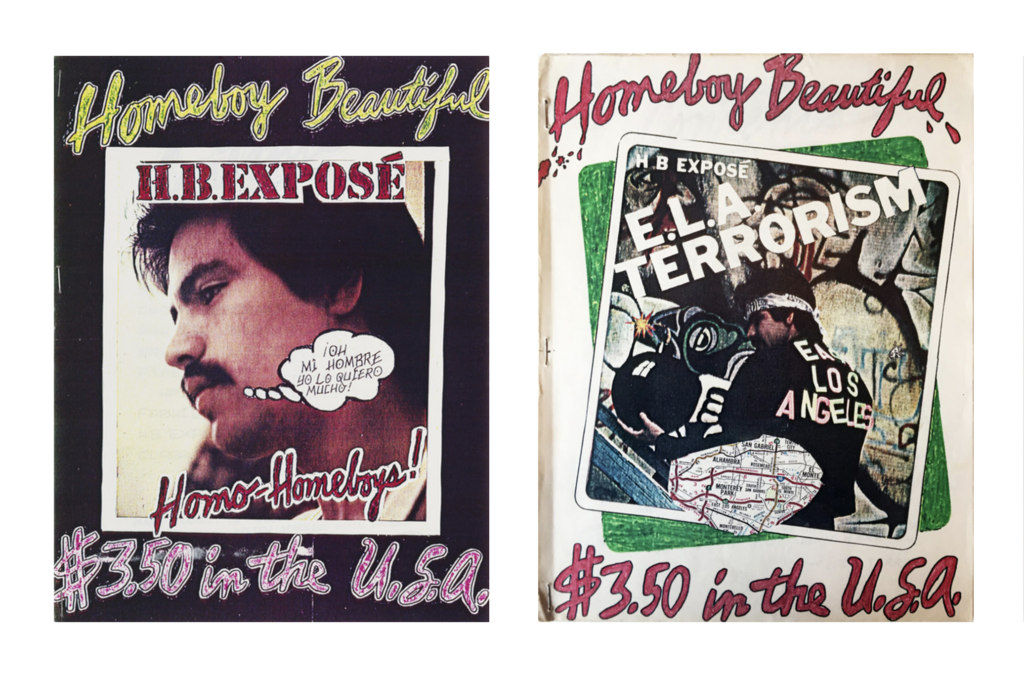

Homeboy Beautiful, Vol. I, 178, and Vol. 2, 1979

In 1978, Terrill released the first issue of Homeboy Beautiful, a self-published magazine that addressed machismo and homophobia in the Chicano cholo culture. With biting humor, the issue included beauty tips, an “Ask Lil Loca” advice column, and a mock investigative piece exposing the epidemic of “homo-homeboys” in East Los Angeles. Friends and collaborators like Teddy Sandoval appeared on the pages of Homeboy Beautiful in photographs or as characters in narratives. Joey admired the expressive practices characteristic of the Chicano homeboy culture—the calligraphy, baggy khaki pants—but in his magazine, these elements were delinked from homophobia. Across both issues of the magazine, radical queer sexual politics stood at the forefront.

Although a third issue never materialized, Homeboy Beautiful circulated through Los Angeles queer networks and beyond. Terrill shared copies with Ray Johnson in New York, often regarded as one of the originators of mail art in the United States. More than a magazine or mail art, Homeboy Beautiful serves as a historical document of a network of queer artists and their contributions to print culture from an unapologetically queer perspective.

“I had this feeling that the party time of the ’70s was coming to a close, and the ’80s were going to be different,” Terrill confesses. After some time in New York, Terrill returned to Los Angeles at the height of the AIDS crisis. “Once HIV and AIDS hit, my work shifted towards focusing on that impact on our community.” The artist contributed as best he could, from joining Act Up demonstrations and participating in legislative visits to working in hospice care for AIDS patients.

Joey Terrill, Chicanos Invade New York, 1981.

In 1989, Terrill was diagnosed with HIV, and his art and activism reflected this new reality. That year, he published Chicos Modernos, an educational safe-sex comic tailored towards Spanish-speaking hustlers and sex workers in Hollywood. Terrill’s comic communicated vital information about safe sex and dating to a community devoid of Spanish information and resources. At a time when tabloid journalism sensationalized ill-stricken bodies, Terrill’s representation of AIDS prioritized a humanistic sensibility. Portraits of friends and loved ones were bright, intimate, filled with love and beauty.

After starting a trial for Crixivan in 1997, Terrill began his still-life paintings, an ongoing series that centers his HIV/AIDS medication on a kitchen table surrounded by everyday items. Foregrounded by a table with a colorful sarape, his still-life series depicts household objects along with his HIV medication. “My goal was to have people that weren’t involved in HIV or AIDS that had fears or biases towards AIDS, to be able to look at the medication in a familiar site,” shares Terrill.

Joey Terrill, Still Life with Crixivan, 1997-98. Mixed media on canvas.

A household name in the Chicano art world, it took decades before the broader art world caught up with Terrill’s work. “I was turned down maybe by at least four galleries throughout 15 years. They would inform me that my work is either “too gay, too queer, or very Latino.” That all changed thanks to the 2017 exhibition Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., co-curated by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz. Hailed as the first historical exhibition on LGBTQ Latina/o artists ever organized, the exhibition introduced audiences to lesser-known histories.

Since then, Terrill has been busy keeping up with exhibition requests and new work. After 19 years of service at Global Advocacy and Partnership for the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, Terrill retired from his director role in 2021 to focus on his art practice. He is currently represented by two galleries: Ortuzar Projects in New York and Marc Selwyn in Los Angeles.

At 69, Joey Terrill has been HIV-positive for 44 years, and nothing can stop him. He remains the keeper of his friends and loved ones who are no longer here to share their stories. He will continue his still-life series until there is a cure or he dies, “whichever comes first.”