Oscar Nñ is a Honduran American creative, Brooklyn-based DJ, and a co-founder of Papi Juice, an NYC art collective that aims to affirm and celebrate the lives of queer and trans people of color. Oscar sat down with Latina’s Alissa Lopez Serfozo at Papi Juice’s studio in Bed Stuy to discuss the experiences that have shaped him, his current interests, and his buoyant desires for safe and welcoming QTPOC spaces. Tune into Oscar’s Sh*ts n Gigs feature to hear him elaborate on his preference for the term Latine rather than Latinx, Honduran visibility, the radical power queer bodies share on a dancefloor, and Papi Juice’s triumphant return to nightlife after sixteen dormant months (their eighth anniversary event sold out in just seven minutes).

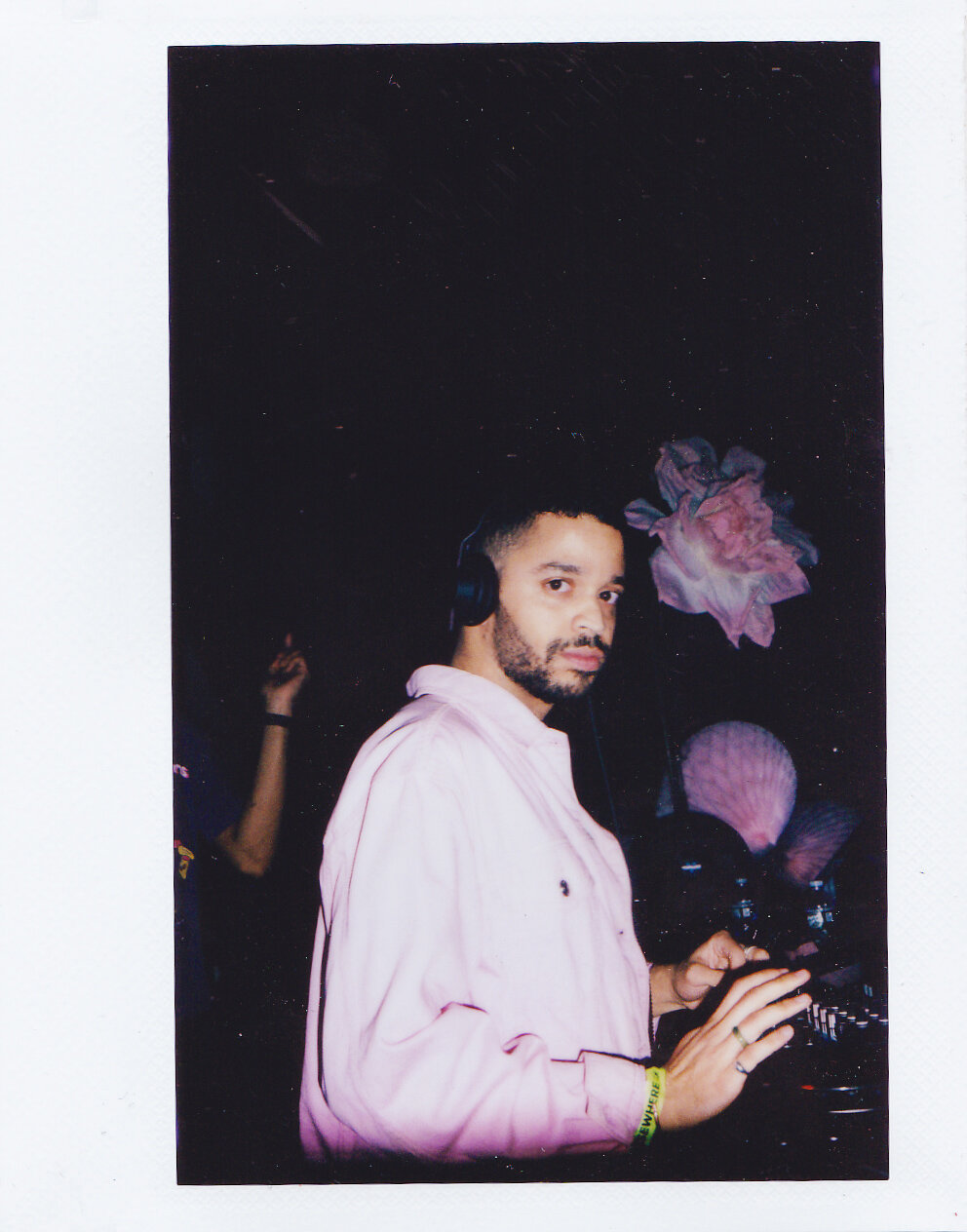

Oscar Nñ DJing a late night set for Papi Juice. Photo by Nicole van Straatum.

Oscar is a mixing maestro with an adaptable and ever-growing curiosity. His DJ sets are amalgams of personal experiences, unexpected interests, and the fascinating community of creative Brooklyn peers (and queers) in his orbit. One of Oscar’s sets might explore and unpack archetypes of an individual genre, for instance, a focused reggaetonera or bolero mix, while another might mesh different styles, like sugarsweet pop with baile funk beats or gabber sequences with r&b classic ballads. Oscar’s willingness to tackle an array of genres and subcultures explains his unique success as a DJ: he creates sonic environments with energetic variety that also promote a collective sense of celebratory exploration.

Working creatively alongside illustrator/art director Mohammed Fayaz and DJ Adam R, Oscar is one of the three co-founders of Papi Juice. The trio’s creative partnership dates back to 2013. Since then, Papi Juice has thrown 62 euphoric gatherings, sweaty dance parties that occur from sunset to sunrise, and multi-generational backyard hangs. By centering queer and trans people of color, Papi Juice has also reframed expectations surrounding the culture, safety, and gaze of NYC nightlife. More than just another Brooklyn warehouse rave series, attending a party might feel more like an affirmation of expansive individuality and the beauty inherent in dancing in a shared space. Music pulses throughout different rooms, ASL interpreters are on hand, people are gorgeous and ready to share compliments, DJs inject sexiness and humor into their sets, stages are wheelchair accessible, and everyone is ready to move freely. Oscar often wraps up a Papi Juice night with a final set slotted to begin anywhere from 4 to 4:30 a.m., chasing the sunrise.

Papi Juice’s Brooklyn-based Founders: Oscar Nñ, DJ Adam R, and Illustrator/Art Director Mohammed Fayaz. Photo by by Papi Prada.

Papi Juice’s community is not only active and connected within New York’s nightlife scene, but also increasingly visible in the larger NYC network of coalition building and mutual aid organizing. In the past year, the collective has executed programming with partners like Planned Parenthood, Brooklyn Liberation March, Marsha P. Johnson Institute, and The Okra Project. As a Papi Juice key player, Oscar has also used his group platform to generate momentum with those who share common values and goals. He has stepped out as a queer Latine individual seeking to improve the lives of others, especially trans and femme people of color.

A Papi Juice Event at Brooklyn’s Elsewhere Venue. Photo by Bashira Webb.

Moreover, Oscar is also driven to growing artistic and cultural solidarity with fellow members of the Honduran diaspora. The Honduran American community makes up the eighth-largest population of US Latinos and in the past two decades the Honduran-origin population has increased 296%. Whereas today’s US media landscape most often depicts Hondurans with reductive tropes surrounding violence, migration patterns, and US-Mexico border relations, there exists a dearth of portrayals of Honduran creativity and artistry. While Oscar is certainly an active part of the community of Latine creators pushing back against disproportionate hostility and bleak Latine struggles in the US, he’s also positioning himself as a proud Honduran. He hopes to develop the creative synergy he’s nurtured with Honduran creative peers into actualized visibility and ongoing influence.

Oscar Nñ represents many things. To name a few: Brooklyn vitality, liberating remixes, Honduran pride, Queer Solidarity. He is also a kind and introverted person who thinks critically, dresses comfortably and fabulously, builds community masterfully, and empathizes with the lived experiences of those around him. This Honduran and Latine creative has set forth a thoughtful and significant legacy in NYC’s QTPOC network in eight exhilarating and hustling years.

View this post on Instagram

Transcript of Oscar’s Sh*ts n Gigs feature below. Conversation edited for clarity.

Oscar Nñ:

I’ve been thinking about the words Latine, Latinx, and Latinidad a lot lately. There is a lot of criticism against these words and against a term like Latinidad, because of how [it can put us] into a singular box. Latinidad is not a monolith or a singular identity. We are complex individuals from different parts of the world. Going from Central America to Patagonia/Southern Argentina, there are very different experiences, lifestyles, and even different weather.

It’s interesting to me to challenge that notion of Latinidad and Latinx [as a monolith]. But also, there is something that’s useful about these terms: they allow us to create and consolidate our power in some ways. Especially within the US, we’re able to [emphasize] cultural [similitude] that we have with other folks from Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. We can organize and build movements through that power and identity of Latinx or Latinidad.

I do identify as Latinx. I always tell people that I’m Honduran. That’s something that I always try to bring up in conversation. If somebody asks me where I’m from, I will always say I’m Honduran American before saying Latinx.

We put so much weight on the singular meaning of words, but language is forever evolving. This isn’t the perfect term and we’re going to keep searching for [a better] term. And maybe that term will evolve as well. Right? [Latinidad] is never going to be an all-encompassing, all-recognizing, and all-inclusive term.

I really like the movement towards adding the E instead of the X: Latine. It sounds nice to me. It also goes back to [the Latin roots of the Spanish language], and I find that it feels more grammatically appropriate.

Alissa Lopez Serfozo:

That’s the thing, no one really knows how to say Latinx. it’s hard to address. Sometimes people will pronounce it “la-teenx.” I do think Latine has a certain flow to it.

Oscar Nñ:

It’s interesting that we’re having this conversation together. I’ve just finished a consultancy for a local arts nonprofit, where they asked me to think about the different ways they can improve their engagement of Latinx and Spanish speaking audiences. So, I’ve been thinking a lot about the intersection between language and identity, as it pertains to Latinx, Central, South American, and Caribbean folks.

For example, with my artist name, Oscar Nñ, I was thinking about how I wanted my name to resonate with people. I didn’t want people to question where I was from. I wanted them to know from the jump that this is somebody that’s from Honduras and Central America. It was super important for me to have this Latine and Spanish speaking connotation attached to my name. And that’s why the ñ is there.

There have been multiple times when people aren’t able to put [the tilde] in the flyer. Because of the typeface, they texted me [to ask], “oh, is it okay if your name doesn’t have the tilde?” Or sometimes they don’t even text me, “oh, sorry, we just couldn’t figure it out.” I’m always like, “no, you have to include it. [The tilde] is part of my name, you know.”

Alissa Lopez Serfozo:

Latinx people are often erased and Hondurans are especially erased…. You’ve shared that you identify as Honduran American even before Latinx at times. What does it mean to be Honduran American today?

Oscar Nñ:

There are always specific identities that are tied to you. We’re in New York and the amount of times that I walk into places and they’re like, “Yo, what’s up? Are you’re Dominican?” And I’m like, “Nah.” And then they’re like, “Oh, you’re Puerto Rican?” And then they’re so confused. And I’m like, “No, I’m from Honduras.” And they’re like, “Ohhh.”

Most of the time it’s kind of funny to me, or it’s cute. Sometimes it’s offensive. But most of the time I don’t mind, especially when it’s coming from a place of interest and love. That’s why it’s super important for me to talk about my background: being from Honduras. My family [has all] grown up there and [we] have lived a lot of our lives there. It’s important for me to talk about that, especially today when there are a lot of caravans of immigrants coming from Honduras. You know, last week, the vice-president went to Guatemala and told people from central America not to come [to the US]. [Editor’s Note: On June 7, 2021 US Vice President Kamala Harris visited Guatemala to conduct a bilateral meeting with Guatemalan President Giammattei to address the issue of illegal immigration. Speaking during a news conference she said: “I want to make clear to folks in this region who are thinking about making that dangerous trek to the United States-Mexico border. Do not come. Do not come. The United States will continue to enforce our laws and secure our borders.”

Then I think about, well, what if we [Central American people] had the option of telling you [not to] intervene in all our governments, our trade,our economies, and our different policies. We don’t have that option, yet you are telling us that we don’t have the right to come [to the US].

There are people literally escaping state sanctioned violence in Honduras today, and that violence is due to and fueled by some US policies that age from the 1960s to today. So, it’s really important for me to raise awareness about that: what it means to be Central American and Honduran today. Whenever I get the platform, I’m always excited to talk about it. Hopefully it hits home to someone, because I wish that I had somebody [like me] to look up to when I was growing up.

Alissa Lopez Serfozo:

What has your personal experience been around the idea of shame? Does it intersect at all with pride? [Is there perhaps] something that once was shameful for yourself, and that now you are actually quite prideful of.

Oscar Nñ:

My friends and I have been talking a lot about how [Pride Month] is supposed to celebrate people and center joy, wellness, and the lives of people. But at the same time, it’s also the time when we get tapped to do the most things. [We are asked] to do everything this month.

We exist all day, every day; all days, every year, every month. You don’t have to hit me up to do something in June. It would be so much more impactful if we did this on a Wednesday in November, you know. Even though [this month] is supposed to center our life, joy, and our people, this is a time when we feel the most stressed, overworked, and sort of taken advantage of because of our identities. My experience in general with Pride varies a lot. It’s the birth of Papi Juice. It’s been a journey for us, even as an art collective, with our intentionality and our way of working. We’re [still] constantly shifting.

We’re not perfect. We’re always evolving in how we’re talking about things and thinking about our work. At the end of the day, we do want to make [Papi Juice] as inclusive as possible to everyone, while knowing that we cannot include everyone at the same time. We can’t be the representation of everyone because at the end of the day, everybody under our umbrella is a different and of a different experience. There are multiple experiences to be had and it’s a very complex [dynamic].

[Going back to Papi Juice’s early days], we had a party at a [bar in Brooklyn] that went well. It was the busiest night that they ever had. [Afterwards] we had a meeting with [the owner of the bar, I think she’s Latina] where she told us, “You guys are more like cafe con leche on a Sunday afternoon. I don’t think you can have a night here [again]. We’re not a gay bar, so we wouldn’t want to be known as one, and we already have a gay party. So, we can’t give you a night here [because] you’re kind of niche. How are you excluding white people from your space?” That was her response to us after we gave her a sold-out show; that was how she treated us.

It was important to make a space where we all felt like our extended families could come, feel seen, and be represented in their own ways. I want my trans friends to come and feel seen. I want my nonbinary friends to come and feel seen. My lesbian girls to come and feel seen.

It’s not perfect and it may not happen in that way, but I hope that every day and every event is a new learning point for us. I hope that we keep evolving and hopefully at some point it feels right to most people or the people that attend.

[On the topic of evolving collectives], we were four members for a while. The fourth member was our in-house photographer, but as time went on, our missions changed. So, we parted ways. Now we get to work with a different photographer for every event. For every single event, it’s another queer or trans person of color that’s taking the photos. That’s something that’s important to me.

We also have a strong policy against outside photography at our events because we were finding that there were people coming in, especially those that weren’t from the community, that were trying to take photos. We felt like it was a violation of the privacy of our community and of [Papi Juice’s] mission. We’re here to celebrate queer and trans people of color’s lives, but we don’t want it to feel exploitative. We’re not here to exploit that joy or the lives of our community members…. That’s why it’s important for us to document our spaces in our own ways, by people that we trust, love, and have relationships with, whether it’s friendship or a working relationship. We’re always excited to work with different photographers.

Nightlife is very much an affirming space for relationship and friendship building, especially for queer people. There are not many opportunities where we get to feel like we’re in the same room together and nightlife kind of serves that. There’s so much power in that. I always think about the power of feeling in the majority. I feel like straight cis folks, especially cis white people, can walk into almost any room today in the United States and feel like they have more power because they’re the majority in a space. I feel like we deserve that power and to feel that powerful.

That’s kind of how our networks have grown and expanded. I love going out, and you’ll usually catch me going out at least once a week to little bars here and there. If my friend is playing anywhere, I’ll go see them and support their set. That’s something that’s always been important to me. It has been a good way for me to build a network of musicians, producers, and DJ friends. I’ve been able to attend different shows and try to connect with folks afterwards or before. Sometimes I don’t get to connect with the performer or the artists that I’m going to see, but then if I ever want to book them, I can just say, “Hey, I was at your show and loved your set/your performance. We would love to work together.”

I think nightlife is something that’s important for the growth of our peer network. [During Covid] our communities couldn’t gather to celebrate joy. [But] we felt that it was important for us to build spaces for our community to feel anger, sadness, and mourn together. Those spaces are equally as important as joy, you know. [Life’s] a journey and we can’t just be 100% joyful and happy. There must be time for mourning, for acceptance, and growing into your own emotions. We felt that last year, our community needed those spaces.

For example, when Pulse happened, I knew that I personally needed to be a part of something where I could have a moment to mourn with my community. I remember I went to one event that was organized by somebody else. I think it was city sponsored. I remember being there and feeling so sad because one, they were reading out the names of the victims and nobody could pronounce the names [properly]. For me that was extremely, extremely triggering. Two, the main speaker was a Jonas Brother. I was just like, “The dissonance of this event is so frustrating to me right now.” I remember being really upset and vocally upset at that point. Then a white woman turned around and said, “You should be happy that he’s here and that he’s raising awareness around it. It’s an honor for you.” I had to leave after that.

I remember that I was just so sad on my way home on the train and crying because I felt like I couldn’t [let out my sadness in an accepting collective]. Then, a week later, a couple of friends and I decided to do something about it. We threw an event at the last minute. We had one week to do it and we just did it.

That’s kind of how we fit into [community] organizing lately. Whenever we see a need and feel like there’s something that needs to be done to uplift, support, and have our communities heal from the trauma that we’ve been facing, we [understand the importance of organizing an event that allows us to do so].

Our work lends itself to that. And that’s the cool thing about being an art collective, where we can get creative, weird, and experimental in the ways that we see and fit into the needs of our [Brooklyn] community. [For example], Brooklyn liberation is something that’s been so beautiful and there’s definitely a bigger coalition that’s a part of it. I play a very, very, very, very, very small supportive role. So I don’t want to take any credit from that but it’s something that’s so beautiful and I’m so happy to uplift and amplify in any way that I can.

I did also play a part in the protect Asian lives rally that we had last in the spring. And that felt really important because our API plus families were struggling with all of these violent events that keep occurring in that community. So that was something that felt really important. And I was really proud to be a part of that as well. For us, [it’s about] finding out where and how our community needs us. Because again, just as important [as it is to] center moments of joy and celebration, I think it’s important to also think about mourning and sadness. And what does that mean? How do we heal to go back to these joyful events?

Alissa Lopez Serfozo:

We’ve been talking about both joy and mourning. For me, [music] is a kind of media that often readily expresses a multitude of experiences. I recently was speaking with someone who discussed how so much of the Latinx/Latine/Latinidad diaspora today is amplified through music. Even for cultures that don’t include people of Latin American descent, [through music] they learn about Latin music and therefore about [Latin] culture.

You are someone who mixes music. Already music is something that naturally spreads a kind of awareness, but also, you’re remixing that [meaning] too. I want to ask you about some of the sonic inspirations that you are working with. [Earlier in our conversation you brought up] an image about being in la sala with your family. [Do you touch on] nostalgia and certain moments that are intimate to yourself when you mix?

Oscar Nñ:

I have a very interesting relationship with nostalgia as a general feeling. It’s funny. I don’t like to feel like it’s something that pushes my work, because I find that nostalgia is something that, at least personally, doesn’t allow you to grow. It’s something so specific to us and from such a specific time that it doesn’t allow room for growth. So, I often think of those moments of being in la sala as part of my lived experience [that] got me to where I am, but that doesn’t define me. It’s a part of a multitude of experiences and lives that I feel like I’ve lived sonically, at least. That’s a huge inspiration of mine to try and mix all of that together and have it [speak to] what the experience is today.

We’ve been talking a lot about what it means to be Latine, Latinx, Central, South American, or Caribbean today. For me, it’s very important to think about: “Yes, amo el perrero. I love a good reggaeton song. Bad Bunny, we love.But at the same time that’s not the only genre of music that’s coming out of Latin America. There are histories and legacies of experimental music from Latin America, including electronic, [but also] all sorts of [other] music. I always love challenging this notion of, “Oh yeah, you’re Latin. You’re a Latin DJ, and so you’re only going to play reggaeton.” No. I’m grateful for folks to give me the room to experiment and to draw from all the different moments in my life that have inspired me.

Alissa Lopez Serfozo:

What’s the most Libra sh*t you do?

Oscar Nñ:

Oh my God. I’m so indecisive. I’m so, so indecisive. Oh, it’s so demonic. I’m indecisive but I have very strong opinions. So, for example, when I’m with friends and we are picking a place to eat at, I will put out all of these different options and then, when my friends [suggest] something, I’ll say: “No, but what about this?” And then they’re like, “[If] you wanted that from the beginning. Just say that.” I feel like that’s something I do that’s very Libra. Very not good and exhausting.

Alissa Lopez Serfozo:

We’ve talked about the idea of how joy can coalesce with pain and struggle. That is something that is manifest both in experiences and memories. [It’s also manifest] in looking back and looking forward. On that note, I want to ask you if there’s any particular memory that once made you feel like sh*t and how do you find humor in it now?

Oscar Nñ:

When I finished college, I had to move back to my mom’s basement because I was going through the immigration process to become an American citizen. I had to make that choice. It was extremely difficult because I had led a very open life in college. I had a partner and we used to live together. I was, like 21, but we were together for a couple of years. Then I had to move back to my mom’s basement in the suburbs of Washington DC. At the time I felt like it was such a step backwards in terms of my own journey into growing into my queerness and even growing into my politics.

Now that that year is so far in my past, I [realize] it’s led me to where I am today. I wouldn’t be where I am today, in every single way. Even with my relationship with my mom. I had to sit her down at some point and I told her: “Do you realize that I left a partner? You don’t accept me as your queer son. So how are we going to keep having this relationship? You [must] see me and all of my identities, otherwise I will see you only at Christmas. That’s the kind of relationship that we’re going to have.”

That was a huge turning point in my relationship with my own mom, my mami, where she [realized] , “Oh sh*t, you’re right. I need to have more compassion for where you’re coming from, your experience as a person, and be more accepting of that.” I felt like at the time she hadn’t fully accepted that yet. By me moving back and us sharing such close space together, I was able to have this really difficult conversation with her that I’m not sure I would have had for many, many years if it wasn’t for that year. That’s one of the things that I was able to do during that time. I was also able to secure my move to New York. There are positives in difficulty and in conflict. It’s just a matter of how you move past it.

Alissa Lopez Serfozo:

Well, I think that’s a very fitting way to wrap up our conversation. Thank you so much, Oscar, for chatting with me. It’s been wonderful to learn more about your background, more about the work that you do, and just shoot the sh*t a little bit. Thank you.

Oscar Nñ:

Thank you for having me.