At first glance, many might think Cesar Espinosa, 36, is too young to know much about immigration reform. Espinosa, who studied pre-law and political science at the University of Houston, has spent over a decade advocating locally and nationally in many public campaigns. He has fought for immigrant and student rights justice in such cases as the HB 1403 Bill, on Texas in-state tuition, and the Dream Act. As the Executive Director of the advocacy group FIEL, “Familias Inmigrantes y Estudiantes en la Lucha,” in English, Immigrant Families and Students in the Struggle, Espinosa has carved a name for himself in Houston as a steadfast advocate for immigrants’ rights.

Alongside his work with FIEL, Espinosa seeks justice for immigrant families and aims to educate the community on a wide range of issues. “Our mission is to seek justice for the community at large. Anything from having forums to talking to the community on issues like education, health, immigration, COVID, and disaster relief,” Espinosa told LATINA.

The activist Cesar Espinosa. Photograph courtesy of Espinosa.

Espinosa, who immigrated with his family from Mexico City, Mexico, in 1991 at age six, knows all too well the struggles immigrants face as they search for their American dream and a better life here in the United States. “Growing up, I always knew I was undocumented,” Espinosa, who has lived in Houston all his life, told Latina. However, it wasn’t until his senior year that he realized his status would impede his ability to garner scholarships and financial aid.

In 2004, Espinosa started organizing regular meetings with other undocumented youth to provide them with tools to access higher education. “A few years later, we began what’s now FIEL, which is the largest, immigrant-led organization. It was kinda all by accident,” he said, of a time during which he was not only finding ways to advocate for himself as an undocumented student, but also the community at large.

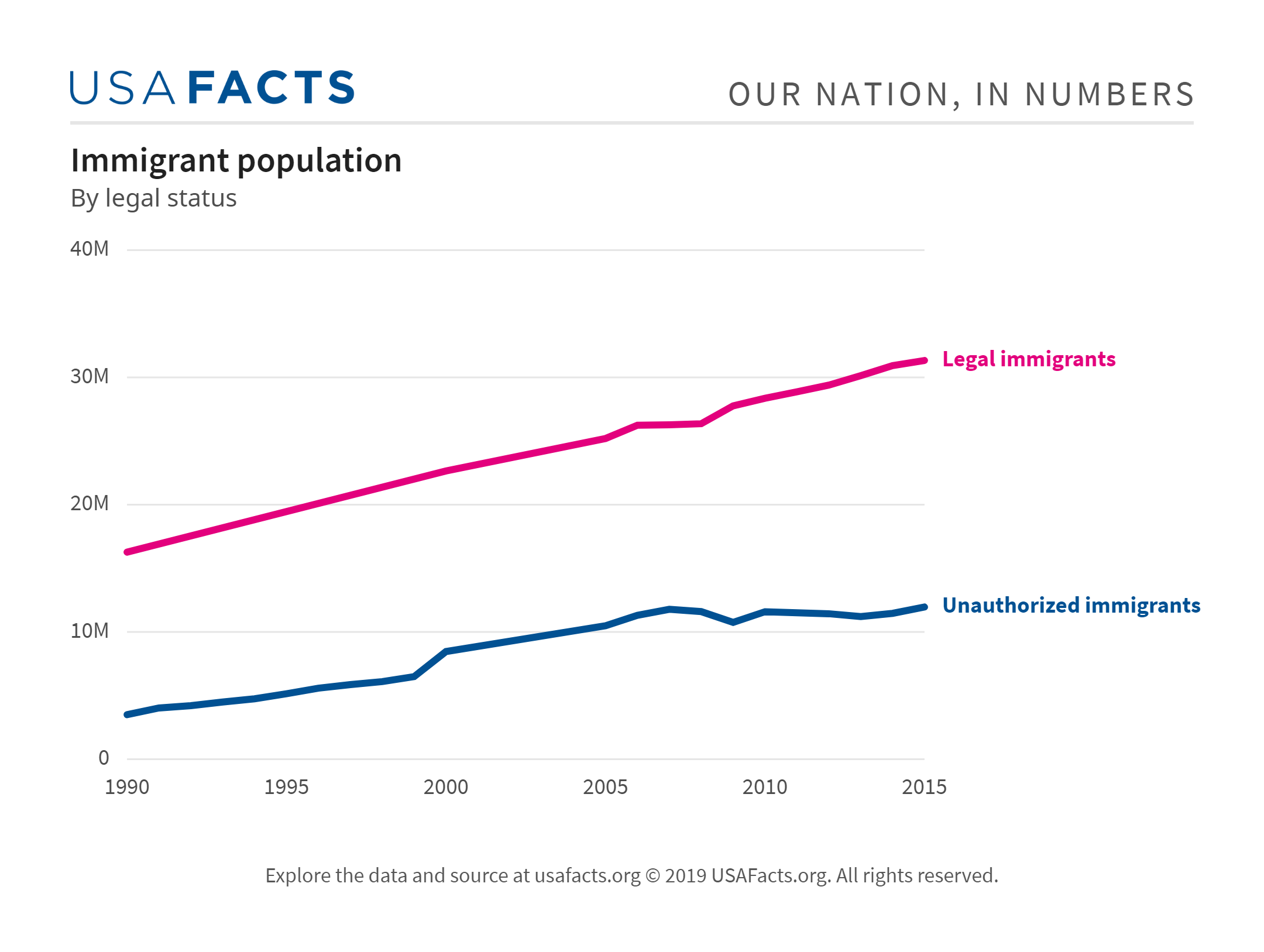

It’s no secret that there are unprecedented numbers of immigrants crossing the border to escape the brutal realities of home. According to the nonprofit and civic initiative USAFacts, “Immigration accounts for roughly half of the yearly population growth in the U.S., and immigrants make up for nearly 15% of the U.S. population.”

In an article by the investigative reporter Robert Arnold on the backlog of cases in immigration court, Espinosa points out that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security miscalculates the extent of the problems migrants face fleeing from a country corrupt with poverty, crime, and an ongoing pandemic.

Espinosa’s Efforts to Reunite the Escobar Family

Imagine spending 17 years creating a life in the United States, only to have it ripped apart by deportation to an unfamiliar country. This was the reality of José Escobar, who was deported in 2017. His wife, Rose Escobar, was left to pick up the pieces of her husband’s deportation and find a way to bring him back home. Espinosa was instrumental in these efforts.

The Escobars were torn apart by an executive order signed by former President Donald Trump that gave Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known as ICE, the right to detain unauthorized immigrants, including those without criminal records. According to an article by “The Intercept,” José Escobar was “one of more than 40,000 people arrested” by ICE between January and May 2017 under what Trump called his “bad hombres” pledge.

According to Rose Escobar, her husband lost his status as a legal resident when he was a teenager after his mother missed a deadline for renewal. He came under scrutiny in 2006 when he tried to re-apply; an immigration court had already issued a removal. The husband, father of two young children, and supervisor of a painting company was granted tenuous permission to stay in the U.S. The caveat was that he was required to check in annually. All that changed in 2017.

The Escobar family. Photograph courtesy of Cesar Espinosa.

José Escobar was deported back to his birthplace of El Salvador following a routine check-in on March 2, 2017. Rose Escobar recalled the events that unfolded that day for LATINA: “My husband got a letter stating we had to go in to see the immigration officer, but I didn’t understand why because we had already done our mutual check-in.” She knew something was wrong when they took her husband to the back and didn’t allow her to go with him: “They dragged me and my daughter [who] was in my arms out of the building, and they just closed the door.”

Escobar reached out to Espinosa for guidance on what to do regarding her husband’s case, as she had many times in the past. The two first met in 2011. At the time, the young activist told her: “I know I look young, but I got this.” Espinosa worked steadfastly to ensure the Escobar’s story made national headlines and lobbied congressional leaders to advocate for the family.

“You know how they say if you can tell your story without crying, you’re healed? I’m still there,” Rose Escobar told LATINA. I could still hear the pain in her voice describing those agonizing years her family went through. She credits Espinosa for helping her husband remain in the country over the years through his knowledge of immigrants’ rights. Rose recalled Espinosa telling her, “You’re not alone; you’ve been here before. There’s a big community that’s going to be here for you. Rose, you got this.”

On July 1, 2019, José Escobar was granted a visa to return home. Today, he is six months away from taking his oath of citizenship. This story is just one of many cases showcasing the determination of a young trailblazer like Espinosa, who stands ready to fight for his community in any way he can.

Jose greets his wife Rosa as she arrives in El Salvador to visit him from Houston for the first time since his deportation. Jose Escobar has been deported, he is the father of two, had no criminal record, and temporary protection from deportation but it was removed under President Donald Trump’s executive order on immigration enforcement. Photograph courtesy of Cesar Espinosa.

A Catalyst for Change

“Sometimes, as a Latino culture, we seem to not want to speak out or not stir the pot in many ways, and that’s what we hear from many of our community members,” Espinosa said. However, it can be a real “catalyst change,” says Espinosa.

In July 2021, FIEL provided a survey analysis report centering on the challenges Latino communities in Houston faced during the pandemic. Issues like growing concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine were at the forefront of the study. “One of the most prominent findings we encountered is that about 87% of surveyed people don’t have access to the internet or a laptop,” Espinosa said. However, he also found that people are willing to talk about their concerns if you take the time to meet with them.

Moments like this can empower the Latino community to speak up and share their experiences as an example for others to come forward. He cited the 2021 case of Juan Martinez Jr. a 15-year-old beaten in his school cafeteria and captured in a viral video, as an example. “In this particular case, we now have a lot of parents coming forward because their children have faced the same situation,” Espinosa said.

Espinosa alongside other community leaders including the late John Lewis. Photograph courtesy of Cesar Espinosa.

Espinosa and his work are gaining attention. In 2021, “The Houston Chronicle” recognized him in a series highlighting Latinos who make a difference in their communities. Still, there’s nothing ordinary about the scenarios Espinosa faces daily. “One of the parts that I enjoy about the work we do is we don’t know where we’re going to end up at the end of the day. As weird as that sounds, it’s one of the most exciting parts about what we do,” Espinosa said. A day of office work can quickly turn into chasing down elected officials, to calling the Red Cross to assist residents affected by an apartment fire.

Espinosa notes daily challenges and sacrifices, but those don’t detract from his goal of being an unwavering resource for his community. “We seek to hopefully start moving the community dialogue so that other people can come forward and we can seek justice together. Espinosa said. “We hope to help craft policies so that an organization like FIEL doesn’t have to exist one day.”