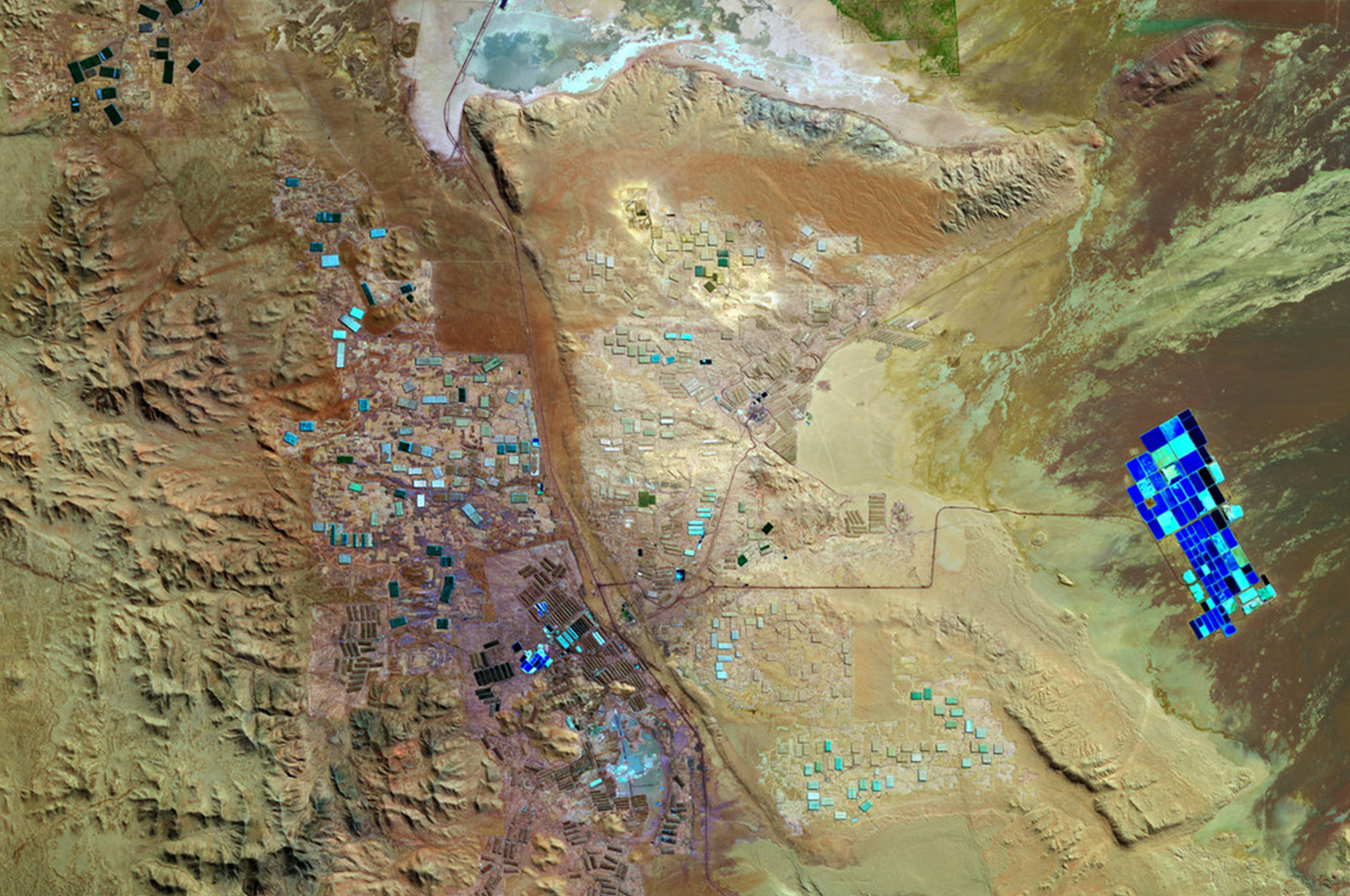

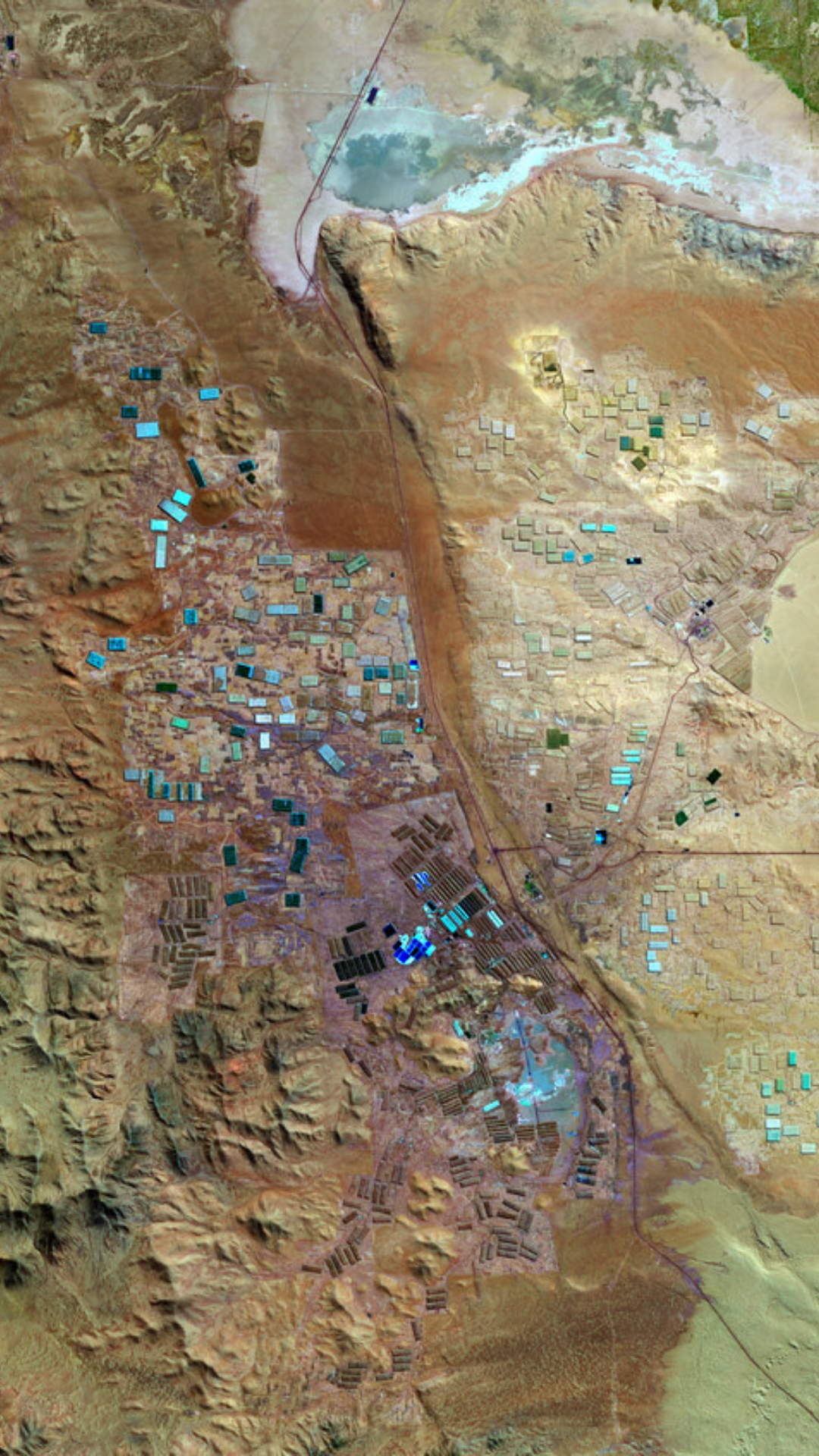

A three-part series exploring the current state of South America’s “Lithium Triangle,” comprising Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile. We explore the challenges each country faces in successfully mining and monetizing “The New Oil.”

During an April 2022 visit to Argentina, his first visit abroad since he was elected president of Chile, Gabriel Boric said to a room of 40 business people from both Chile and Argentina, “The mountain range that unites us, more than separates us, has raw materials on both sides that are rather similar. How we work with greater cooperation and integration is very important.” Boric is referring to what’s now being called the Lithium Triangle, a mineral-rich swath of deposits that gets its name from the way those raw materials transcend borders in Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile.

Boric’s cozying up to Argentina’s center-left president Alberto Fernandez has elicited a predictably mixed response. Some pundits and Chilean citizens alike worry that Boric is too left-wing, while others complain he isn’t left-wing enough. Many though are eager to see what the new president’s ongoing relationship with Argentina and Bolivia will mean for the “electric future,” the global transition to renewable energy that’s inspiring a rise in lithium’s popularity.

That being said, Boric’s first term has already been mired by roadblocks in putting his idealism into action. Support has been faltering for Chile’s Constitutional Convention as well as Boric himself, making it a tough first month in office for the 36-year-old activist turned president. Even his most ardent supporters agree that the boldness of his campaign has been distorted by moderation in his first term, as evidenced by his willingness to speak positively with and about corporate interests in Argentina.

Boric’s approval rating, which started at about 50% when he assumed office, has dropped to 45% in the first month of his presidency. An insurmountable 83% of Chileans agree that the country’s economy, one of the more stable in the region, is either stagnate or actively worsening. As for Chile’s upcoming referendum on the Constitutional Convention, more than 45% say they would reject a new Chilean constitution, which is scheduled to be completed on July 5th of this year.

It’s here that we get some insight into the future of Chile’s lithium. One of Boric’s biggest campaign promises – that he would work to nationalize Chile’s precious metals and minerals – is tied to the success of the upcoming September referendum on Chile’s new constitution. As of now, the chances that a referendum passes decrease with each day, following criticism of what some Chileans have characterized as the group’s more “radical” policies relating to environmental concerns. Namely, the establishment of what Inside Climate News calls an “ecological constitution,” one that would include such provisions as imbuing nature itself with rights to life and the freedom to “exist and regenerate.”

The future of Chile’s lithium is among the most divisive issues at the Constitutional Convention, which was established on July 4th, 2021, with the intention of drafting a new constitution within one year to do away with the country’s Pinochet-era policies once and for all. The Convention is currently deciding whether Chile should go the route of nationalization, or leave the mining industry in private hands. Doing so would allow lithium to continue to be extracted and exported based solely on profit and not for the betterment of the Chilean people.

Boric’s December 2021 pledge to establish a National Lithium Company would completely revamp the country’s economy and put power back into the hands of working Chileans by doing away with privatized resources that allow corporations to reap the benefits of Chile’s lithium with no obligation to funnel profits back into the Chilean economy. A nationalized lithium company would allow the new government to “develop an industry under its wing, which generates added industrial value instead of exporting raw material in its raw state,” reads a January 2022 article from Entorno Inteligente.

The 1980 Pinochet constitution was ratified on the heels of a wave of privatization that only intensified through the next decade. Among the policies implemented by the Pinochet regime was a pension plan that moved pensioner money into private hands, and ultimately devastated Chile’s working class. There was also Pinochet’s 1979 Labor Plan, which “sought to codify the dictatorship’s anti-labor policies,” according to an article in Global Security. “It placed stringent limits on collective bargaining, strikes, and other union activities, especially any participation in politics.”

Hoping to undo much of the Pinochet-era inequality that has contributed to Chilean poverty, the mining industry is one of the country’s best hopes for balancing the economy in a way that benefits Chile’s working class. “Mines and industrial facilities have been at the center of social conflicts over who accrues economic benefits from those activities,” reads an April 3rd article from Inside Climate News, “and who bears the burden of their environmental consequences.”

Predictably, these efforts have been met with disdain from the Convention’s more conservative delegates, who disregarded nearly all of the environmental committee’s plenaries during the week of March 9th. Though the Convention can be characterized as center-left-leaning liberals, a vocal minority of Chile’s right – roughly 37 of the 155 total delegates – have found themselves at odds with the Convention’s far-left factions. “Constituents at committee level need to be able to rewrite proposals to obtain 103 votes at the convention’s floor, otherwise their proposals will be definitively rejected,” said Gaspar Dominguez, Vice President of the Convention. Boric himself has admitted that he’s “worried” about the future of the Convention following the drop in public support.

And yet, the company Lithium Chile has managed to ink a number of high-profile deals with overseas investors since the beginning of 2022, including a recent agreement with the Monumental Minerals Corporation to exploit the Laguna Blanca property, which “consists of 23 exploration concessions totaling 5,200 hectares,” according to Yahoo! Finance. If all else fails, the South American lithium OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) first proposed in 2021 is still very much on the table, especially as Boric strengthens relations with Argentine president Alberto Hernandez and Bolivian president Luis Arce, marking one of the first times in history that all three corners of the Lithium Triangle have been politically aligned.

Ultimately, the feeling that lingers is one of hope. Chile’s people are working to undo the legacy of neoliberal Pinochetism that has ransacked its working-class economy for the last four decades. South America, and the Lithium Triangle within it, have the ability to control the fate of their own sovereignty, and the precious metals and minerals that will revolutionize their respective economies.