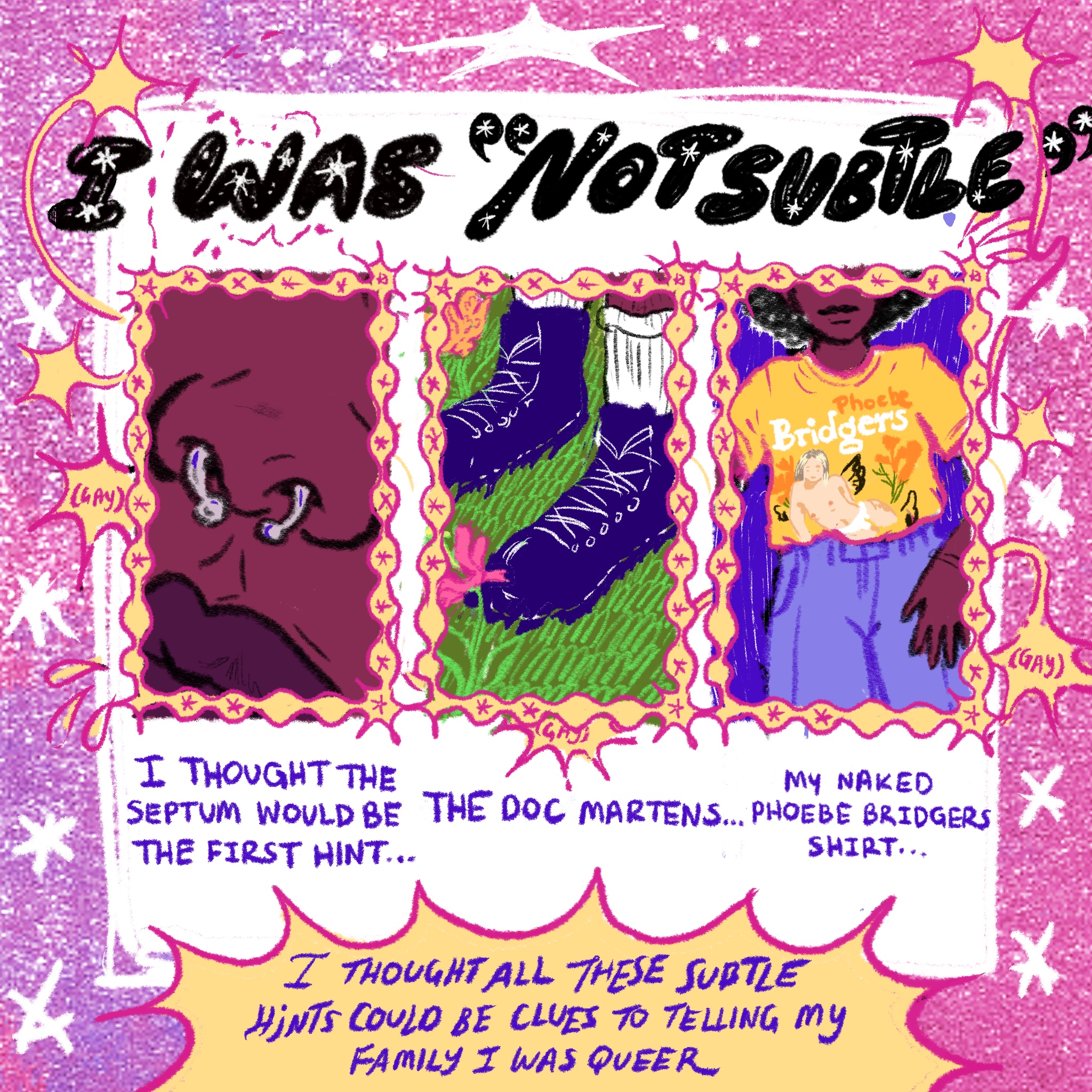

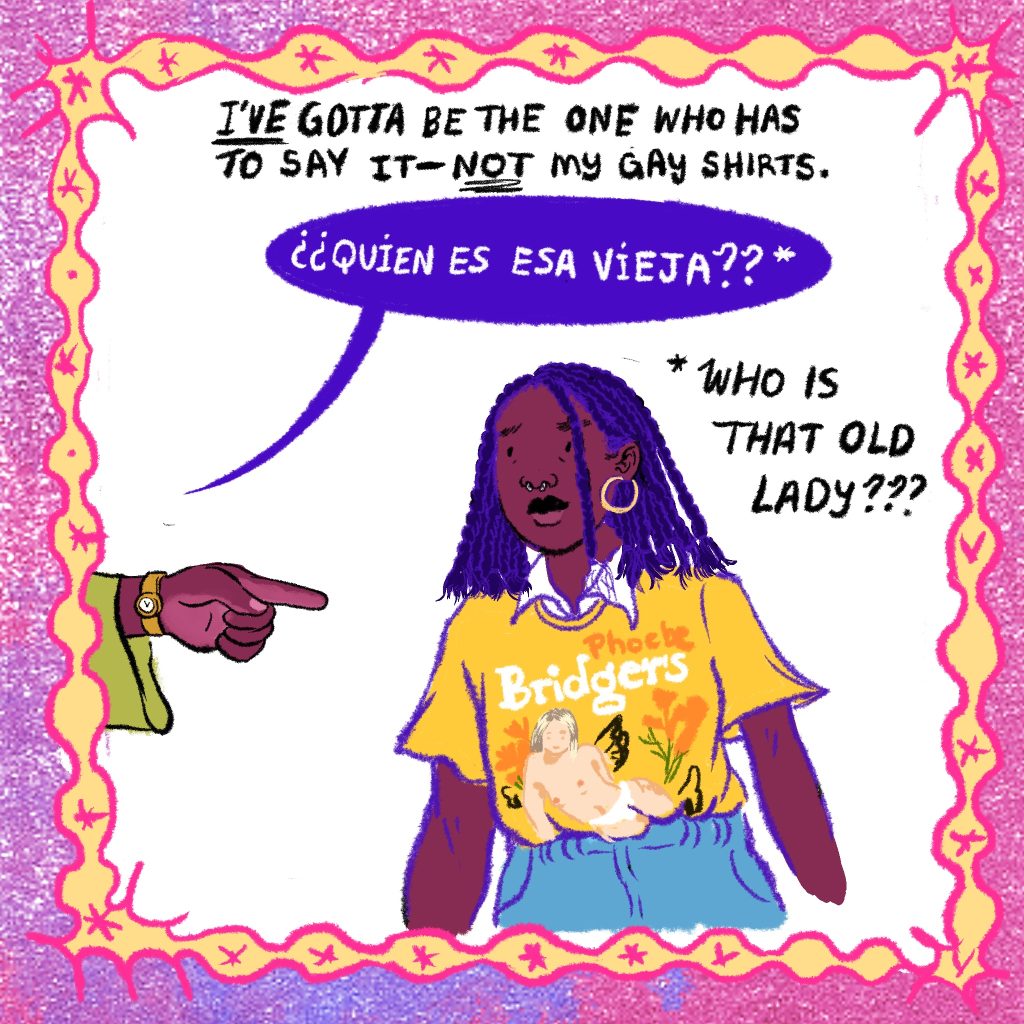

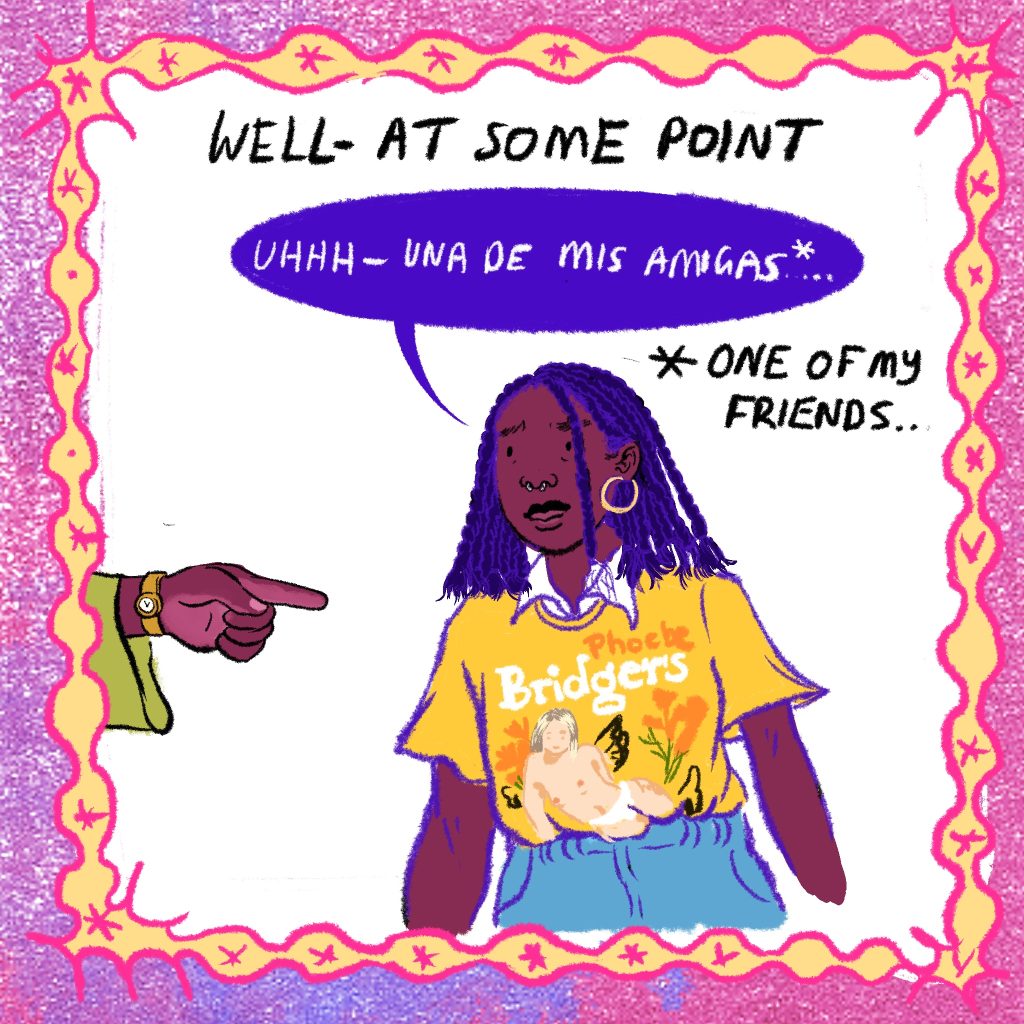

I thought the septum was an obvious clue. The Doc Martens scuffed by random punk shows and hikes, the Phoebe Bridgers shirt my English Professor bought me after, with stains from rubbed off makeup. I thought all these subtly unsubtle hints could be clues to indirectly telling my family I was queer.

The more formal, festive “coming outs” never felt right to me — big balloons grazing walls and streamers flowing down my shoulders. There was never a way I could imagine myself having to utter the words “I am gay”. I grew up with the self-fulfilling notion that I didn’t have to provide that for anyone — that my queerness could just be — and when they knew, they knew.

Of course, after 22 years of not having a boyfriend, my family would prod me at the dinner tables and on the way to parties, but I wouldn’t budge — and I wouldnt come out either. There was never a right pause or time or place. Never a pocket of silence I could claim for myself to utter the meager words. I imagined my coming out scenario to be as clumsy as the words that would stumble out of my mouth.

I could just imagine it — me interrupting my mother over her loud Grupo Niche salsa music, the scent of Fabuloso wrapping around us as I tried to yell over the cacophony that I was gay. This directness, the sharpness, was not something I was used to in a family that relied on passive-aggressiveness.

And so I decided I could use the same tactic for revealing my queerness. I could show them, not tell them. It started with sporadic gay flags — in my rooms, stuck to my water bottles and on my laptops. I had gay pins dotting my jean jackets and backpacks, queer zines and literature stacked on a precarious pile on the edge of my nightstand.

And so when people would ask — ”does your family know you’re queer?”, I would answer with an airy confidence, lifting my chin and fluttering my eyes, “yes”. I was convinced these treasure troves of clues must have led them to the conclusion. I never thought about the possibility of these hints being mere decorations in their recollection.

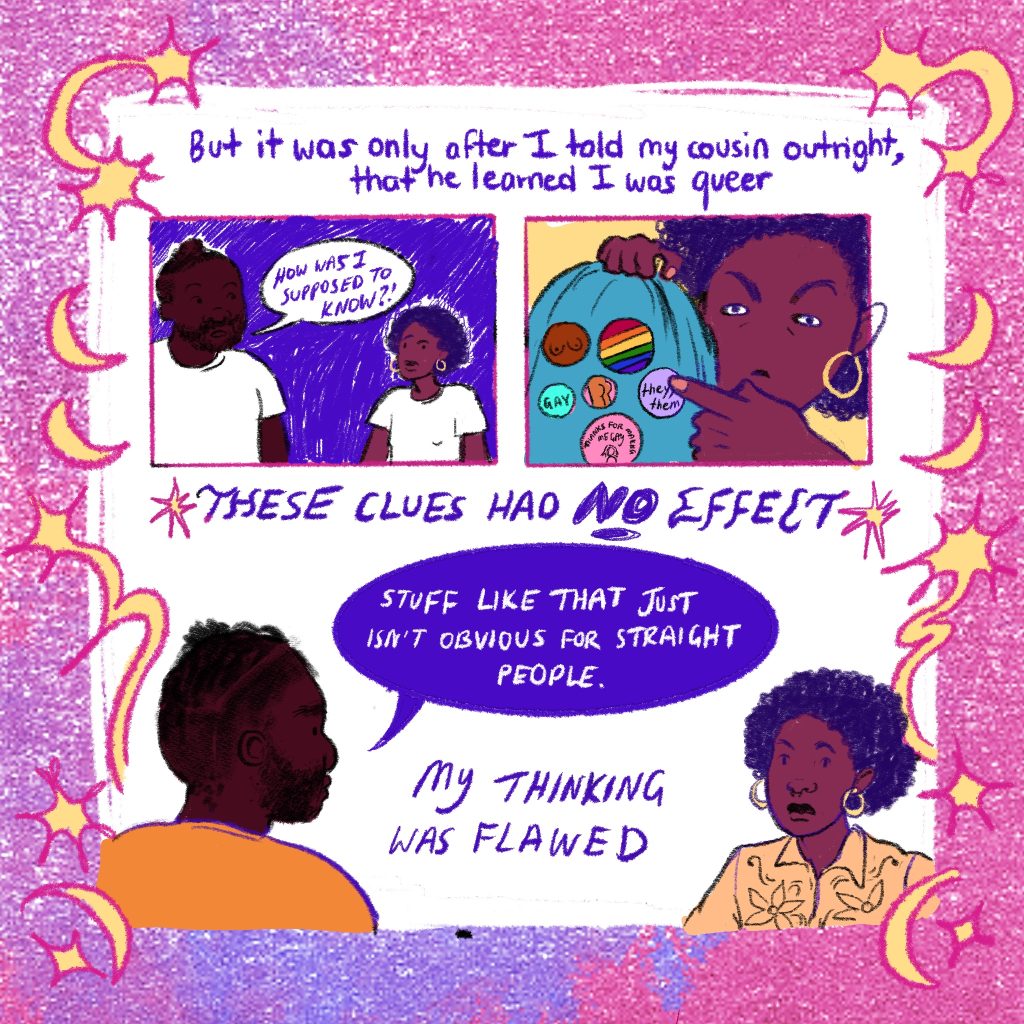

I was hit with this realization when I learned my cousin didn’t know I was gay this entire time. He had only learned after seeing my instagram one time. “But I played cunty gay music in the car?!”, I uttered in shock at his obliviousness. I thought the bubblegum bass of Charli XCX and Coco and Clair Clair thumping in his Tesla as a sonic cue of homosexuality.

“You’re a different generation than we are.” he said. “When people our age see that, we just think oh it’s Gen Z, they’re just doing trendy shit.”

I was shocked — to a degree. And then I realized how these subtle hints were exactly that, subtle. They were microscopic to the naked heterosexual eye, something that could only be known from the inside jokes made in bathrooms at gay bars, on reddit forums.

Especially since I was a queer femme, there were no clear (masculine) markers for my family to realize this. My gay pins were asterisks in their hetero-dominated world.

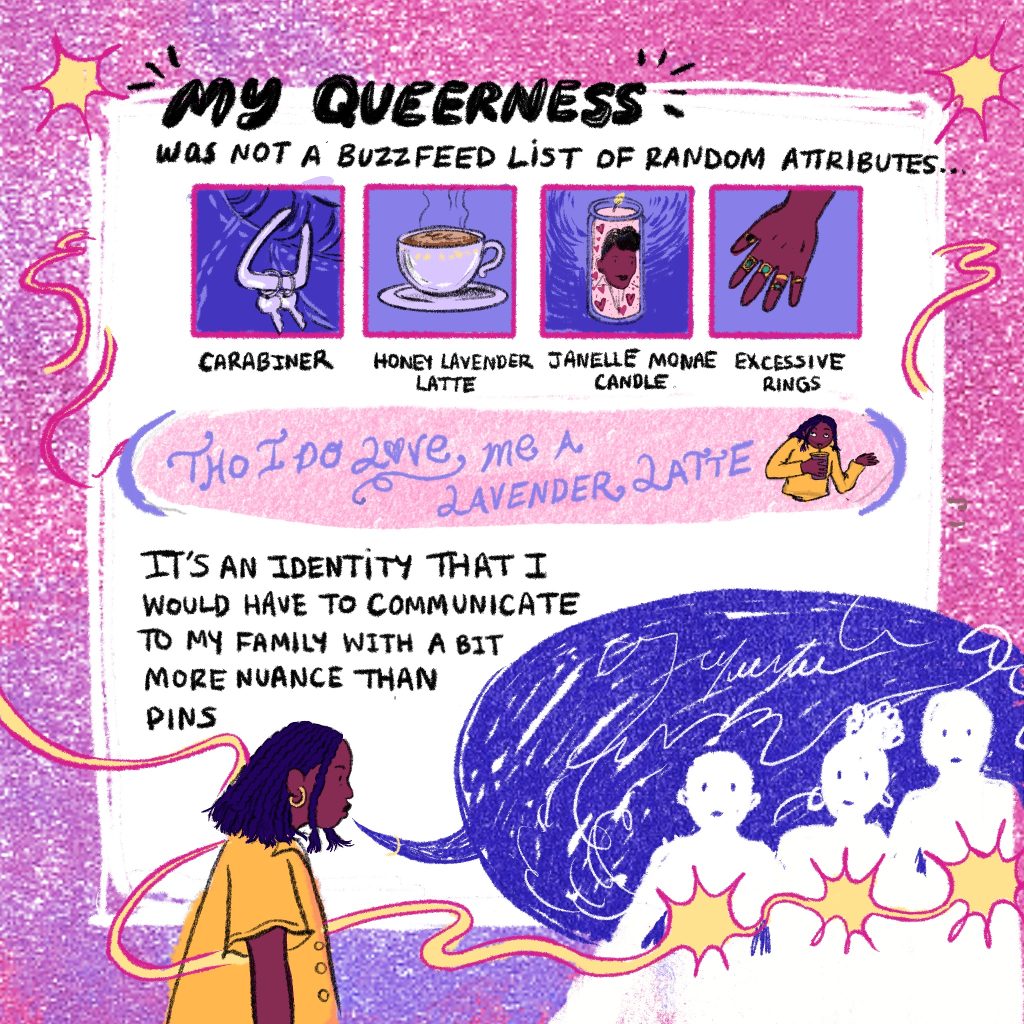

And this concentration on objects representing my queerness was a marker of a more insidious materialist alignment of queer culture.

While I loved the cheeky jokes about oat milk lavender lattes and carabiners that filled #lesbiantok, they always left a bitter taste in my mouth.This thought about looking “gay” through the accumulation of products felt regressive. Of course these were jokes, but these goods become symbols and truth. And these symbols become markers for how and WHO we view as queer.

You see it in queer scenes all the time. I had friends tell me they feel they don’t look gay enough because they didn’t “look” the part. I heard the jokes about donning the right things so that the queer passerby doesn’t think you blend in with straight “normies” on the street. Of course, queer culture has been marked by maximalism and kitsch, but this doesn’t mean that we need to ingrain our queerness with the objects we collect.

Once we align queerness with the objects we have — rather than the rich rituals that we’ve cultivated — we fall into the consumerist trap that allowed the Pride Collection to crowd Target’s storefront and allowed pride toilet plungers and vodka bottles to become a reality.

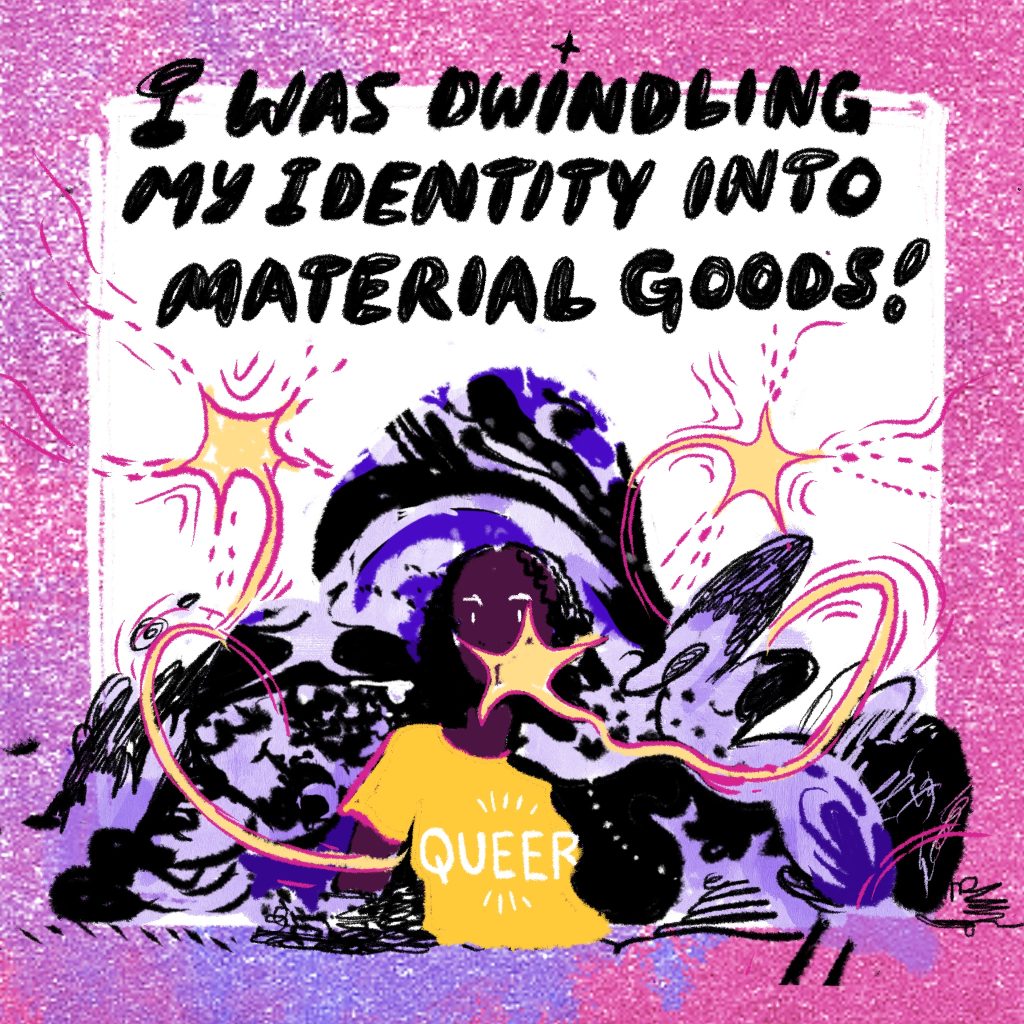

And in using these decorations as identifiers of my queerness, I was also dwindling my identity into commodities.

But of course, queerness was not my tight fitting shirts or water bottles — it was a complex way of being that would need to be translated through more than short nails and pinky rings.

I will have to make them understand the nuance, the gaps, the restlessness, the quirks, the more invisible and intangible facets of the life I’ve been living for about six years now.

And it’s only with this directness that I can speak for myself — instead of Phoebe Bridgers doing the work for me…

It’s just a matter of how… and when?

Arantza Pena Popo is a queer cartoonist and illustrator based in Los Angeles, CA.