As hundreds of thousands of people flock to Manhattan for New York Fashion Week for a chance to see the latest runway looks, creative director Mellány Sánchez’s new installation “Objects of Permanence” pays homage to the thousands of Puerto Rican and other immigrant and migrant workers who powered the Lower East Side’s garment industry and helped cement New York City as one of the world’s fashion capitals.

Sánchez celebrates garment industry trailblazers across nationalities and backgrounds, past and present, by mixing both historical and fictional elements of art in “Objects of Permanence,” presented in partnership between Abrons Art Center and the Tenement Museum through September 14, 2023.

Upon entering the exhibit space, visitors are met with a display of three shirtwaists honoring three of the 146 employees, mostly young immigrant women, whose lives were lost during the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. At the time, the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) had been fighting for over a decade to protect the rights of these workers and continued to mobilize after the tragedy.

“This point in history was important to the legacy of what labor laws and union activism looked like. The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition inspires me to honor the legacy of people whose skill and labor should be acknowledged,” Sánchez tells LATINA.

Mellány Sánchez: “Objects of Permanence,” 6–14 September, 2023.

Photograph by Bre Johnson/BFA. Image courtesy of Abrons Arts Center.

The installation welcomes visitors to imagine they are walking through the home of a Lower East Side garment worker in the mid-twentieth century. It features authentic objects from the time period, such as shears, dresses, sewing machines, photographs, and union cards, alongside the creations of contemporary artists and designers who contributed garments and artifacts that honor garment workers’ lives.

One of these modern perspectives includes a retro-style dress from Christopher John Rogers Pre-Fall 2023 collection that pays tribute to the shirtwaist style. Another displays photos curated by Nuevayorkinos’ Djali Brown-Cepeda and Ricardo Castañeda which feature Latinos whose lives and histories are closely intertwined with their labor in the garment industry.

Another contemporary designer featured in the exhibit is Chilean luxury designer and Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) board member Maria Cornejo, who displays fabrics from her clothing line which is manufactured right in New York City’s Garment District. “At Zero + Maria Cornejo, 85 percent of the collection is made in New York City. It’s imperative that we support and shine a light on our garment workers in the city,” Cornejo says. Other exhibit contributors include Emily Adams Bode Aujla from BODE, Tremaine Emory from Denim Tears, Elena Velez, Kim Shui, Rio Uribe from Gypsy Sport, Procell, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane from Sánchez-Kane and Willy Chavarria.

Installation view of Mellány Sánchez: “Objects of Permanence,” 6–14 September, 2023. Photograph by Bre Johnson/BFA. Image courtesy of Abrons Arts Center.

For Sánchez, a Nuyorican with over two decades of experience in the fashion space, curating this exhibit was personal. Her grandmother worked in a large undergarment factory in the Lower East Side making underpinnings, a trade that was then passed onto Sánchez’s mother, who went to school for fashion and raised Sánchez with not only an appreciation for clothing and style, but also with tactical skills like hand embroidery.

Sánchez says her grandmother was one of the Puerto Rican garment workers in ILGWU Local 23-25, also known as the Blouse, Skirt, and Sportswear Workers’ Union. By 1937, the ILGWU had over 2000 Puerto Rican members. Less than 30 years later, Puerto Rican members made up over 25 percent of sewing machine operators in New York City, according to Hunter College’s Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library & Archives.

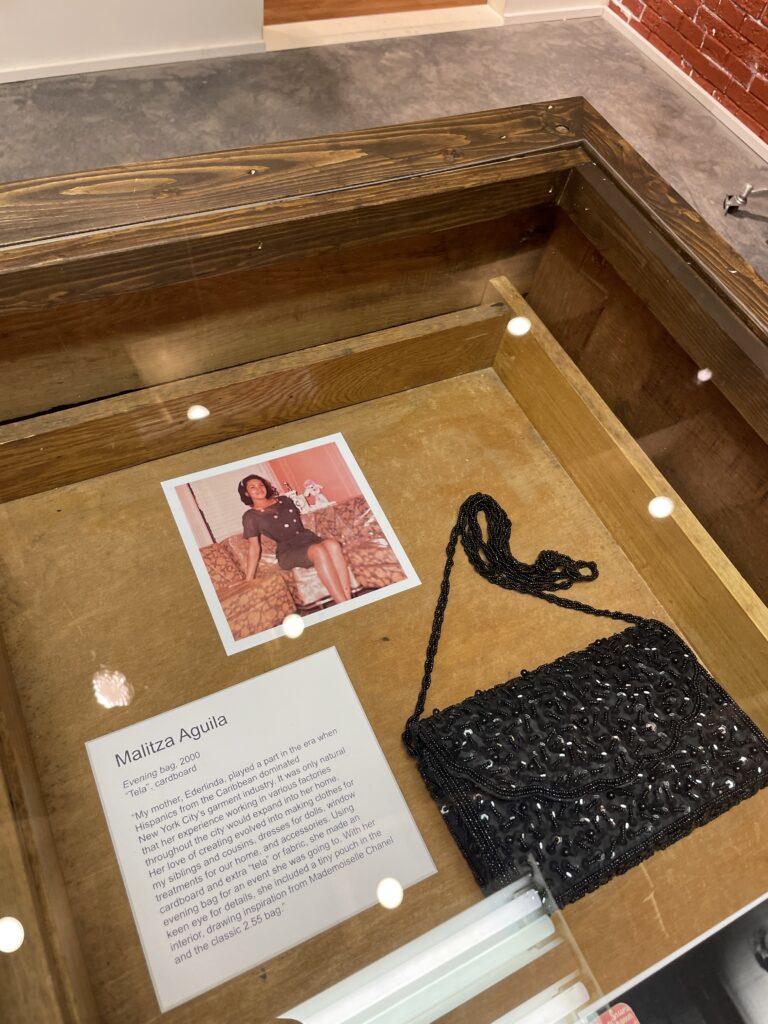

Malitza Aguila is one of the exhibition’s community contributors who shared the story of her mother Ederlinda’s experience working in the Lower East Side’s garment industry in the 20th century.

“While growing up on a farm in Puerto Rico, my mother Ederlinda learned many skills from her mother, aunts and cousins,” Aguila notes in Nuevayorkinos’ photo archive. “When she moved to New York, she honed in on her craft as a seamstress working in various factories in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens which became her only source of income for the next 40 years.”

Struck by Aguila’s story and her mother’s decades-long connection to the garment industry, Sánchez asked Aguila if she still had any of her mother’s original pieces. In addition to sharing two photos of her mother, the exhibit features one of Aguila’s mother’s original creations: a black handmade purse – modeled after the iconic Chanel 2.55 handbag – made from leftover fabric, cardboard, and black beads.

Installation view of Mellány Sánchez: “Objects of Permanence,” 6–14 September, 2023.

Photograph by Bre Johnson/BFA. Image courtesy of Abrons Arts Center.

Aguila says that despite the Garment District’s distinguished position as a birthplace for fashion and design, one must remember how migrant garment workers’ lives were — and often still are — harsh and isolated as a result of their immigration status and work permits.

“While they are often unable to complain about their conditions for fear of being reported to immigration authorities, they are striving to better their lives for their families. They are critical to the workforce and New York City has always been the gateway to opportunity,” Aguila says. “They have helped build the city and its infrastructure and filled many of the jobs that kept it running. We need to champion their story.”

Zameena Mejia is a New York City-based writer whose work has appeared in Forbes, CNBC, Remezcla, Refinery29 Somos and more.