Ingrid Rojas Contreras is soft-spoken, yet her words carve a space to remember. Her debut novel, set in Colombia against the backdrop of political instability and Pablo Escobar’s violent reign, “Fruit of the Drunken Tree,” was a semi-autobiographical novel. It vividly summons the turmoil of Colombia in the nineties by juxtaposing private familial moments with national history. For her highly anticipated and critically acclaimed second book, “The Man Who Could Move Clouds,” Contreras continues to tenderly illuminate personal and overshadowed voices.

In this memoir, Ingrid Rojas Contreras reclaims curanderismo from the shadows of history. Often relegated to magical realism, folklore and superstition, Rojas Contreras’ lyrical personal account says otherwise. To write about her family’s cultural lineage is to reject colonial judgment against Indigenous ways of knowing. Curanderismo is a gift, a medicine against perpetual state violence, an inheritance that exists at the edge of perception.

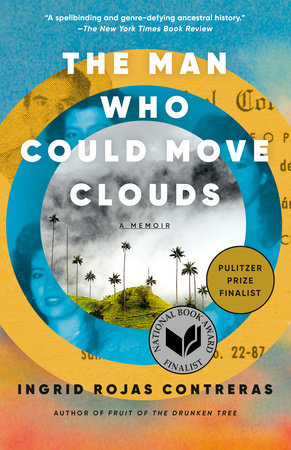

A finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, “The Man Who Could Move Clouds” is a telling of the author’s most valuable inheritance: “the secrets.” Growing up in Colombia, her maternal grandfather, Nono, was a renowned curandero with the ability to conjure spirits and treat ailments. Similarly, her mother could foresee the future and be in two places at the same time. In her twenties, Rojas Contreras inherits her family’s gifts after recovering from a head injury that left her with amnesia. The book interweaves the author’s relearning of her family’s history with a journey to Colombia after shared dreams among the women in her family urge them to disinter her grandfather’s remains.

LATINA spoke to the Pulitzer-nominated author on inscribing the incomprehensible, reclaiming knowledge once lost, and the power of the written word to bring people together.

Courtesy of Penguin Random House.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Your first book was fiction and your second book, “The Man Who Could Move Clouds,” is nonfiction. What went behind that decision?

I always knew that I wanted to write “The Man Who Could Move Clouds”. What happened is that I kept getting the comment that what I was writing was fiction, and that made me angry. I would write about moments like my aunts [and uncles] seeing my grandfather move clouds and I would turn that [piece] into a [writing] workshop and people would say, “Okay, but you know that didn’t really happen. This is kind of fiction.” I wanted to make space and come up with a way that I could claim territory for these kinds of stories in nonfiction. A lot of South American communities have stories like this. A lot of Indigenous communities have stories like this. So it came from a place of, “I’m going to figure out how to [write this] and find my language to do it.”

There is so much power in claiming that nonfiction space because often these stories are labeled as magical realism.

That’s the other narrative injustice that I saw. Often these ways of telling stories are Native to the continent. Then, when people hear magical realism or recognize some magical realism in this book, there’s this mistake of thinking a few writers [of the Latin American boom] came up with this way of telling. One of the things that I’ve said is [my writing] is real magical realism. I wanted to write something that explained the provenance of [magical realism] – where it comes from — and make sure to [show that] it is actually a very old way of telling and relating.

How would you describe “The Man Who Could Move Clouds”?

I think that it’s about telling stories that are at the margin of perception. For example, when my aunts and uncles witnessed my grandfather move clouds, that was at the edge of perception. It’s a place of reality where we don’t know what happened. We know what we saw and we know what we experienced but it’s very hard to put into language what actually took place. Even with the photos that I took for the book, I was trying to document what I think the margins of perception are. And so, any time that somebody would say, “I saw a ghost appear here,” I would photograph it. It was my way to put language [and imagery] to something that’s very hard to pin down.

What does reclaiming curanderismo mean to you?

I think that within South America, and the Latino community as a whole, there’s a lot of healing that needs to happen around anything that is Indigenously rooted because there’s just such a fear of [that kind of “mysticism”]. Some of the things that we say today about skin color, history, or spiritual practices are what European people would have said at their arrival. [Europeans would have said that curanderismo is witchcraft,] a practice that came from people who were mixed, whether it was African or Indigenous or Spanish. To reclaim curanderismo is also to tell this history, to point out when it’s repeated, and ask why things are the way they are. I think that we’re in the place to do that work now. A different generation, even my mother’s, would have been so afraid to admit that my grandfather was a curandero or that my mother was a curandera for fear of the social stigma. Now, we get to have these conversations and we get to ask questions.

Your family’s story is set against a backdrop of continual state violence. What might the relationship between violence, surviving and curanderismo speak to?

When you have such a high scale of national tragedy, loss, and grief, and when people are going through a lot of traumatic events that are very hard to heal from, you need stronger medicine. It’s a different way of dealing with illness, and letting all of your history into the room. It’s a different way of relating.

This reminds me of the chapter in your book where you are holding card readings for your grade school peers and all the heavy questions they would bring to you.

If you were doing a regular card reading it might be “Who likes me? Does this person like me back? Am I going to have this job that I want?” Very practical questions. The questions that I got were, “My father is kidnapped. Will he come back?” or “Are we going to lose our house? Where am I going to be living next year?” Everyone has been touched by the conflict in a very deep and wounding way. So there’s a way in which the nation carries joy and gravitates to curanderismo. All of these practices have to do with that question of, “How do we carry such a heavy thing? How do we support each other? How do we make it through the day?”

I could relate to so many stories in your book. There’s one chapter on gold hunting that struck me as eerily similar to my own family’s stories that took place in Michoacán, Mexico. How often do you get these sorts of reactions from your readers?

I actually get them a lot. It reinforces this idea that we share so much culturally. I imagine part of it is that the migration in the continent was very loose; there was a lot of exchange. The ways that we were colonized throughout the continent are very similar. Even with a Filipino writer, I mentioned that Colombians, when we’re pointing to something, we point with our mouths, and she said, “Filipino people do that too.” And then I heard from a Native American writer that Native American people do that as well. It’s so wonderful to have a place where I’m telling my story and people get to say, “Oh, that’s also like us.” We make connections that I don’t think we would otherwise.

What are you currently reading and what are you working on next?

I’m reading a lot of George Saunders right now because I’m doing an event with him in October. I’m working on something in fiction. It’s been very messy, I just started. It’s going to be a story about either a community of female curanderas or a family of curanderas. I’m still not sure. With all my work, I seem to be very fascinated with the way that women survive hardship and conflict and war, and how women teach young girls to do that. It seems like I’m still gravitating to that theme with this next work. But, you know, anything can change.

Joanna García Cherán is an art historian, writer and cultural worker passionate about art of our time.