A three-part series exploring the current state of South America’s “Lithium Triangle,” comprising Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile. We explore the challenges each country faces in successfully mining and monetizing “The New Oil.”

The three countries inside South America’s Lithium Triangle represent a spectrum of success in extracting and commercializing the region’s lithium-rich salt flats. Chile sits at one end of the spectrum, where the mining of precious metals like lithium — a key component in the global transition to renewable energy — represents a significant portion of the national economy, and Bolivia sits at the other, where until recently, the lithium industry was nearly nonexistent. Argentina exists in something of a middle ground.

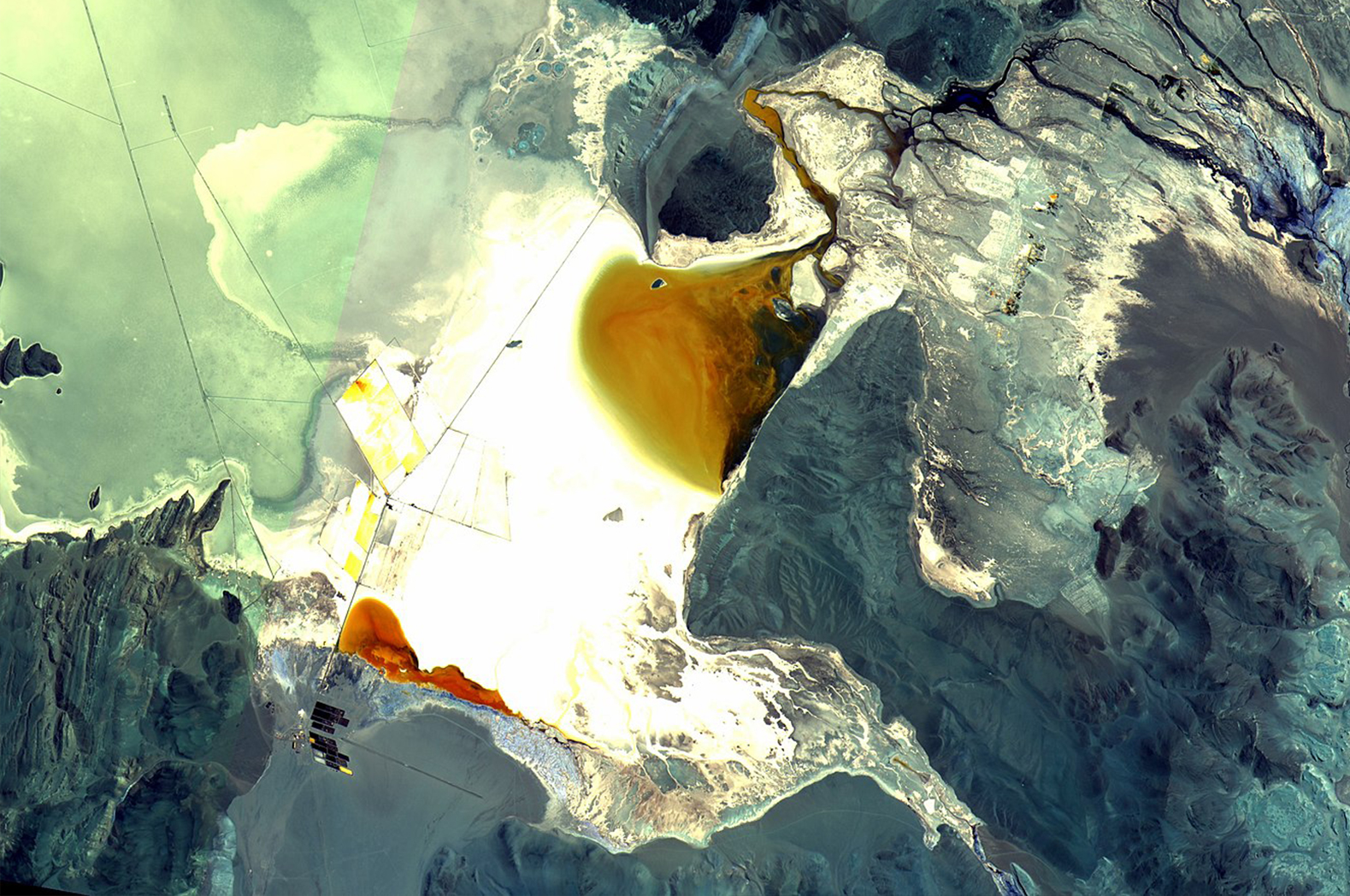

Likewise, Argentina’s lithium output falls between its peers in the triangle. Chile produced a whopping 18,000 tonnes, or metric tons, of lithium in 2020, ranking second in global production behind Australia. Argentina, by comparison, produced 6,200 tonnes in 2020. Currently, Argentina operates two lithium mines: the Incahuasi Project at a “salar,” a salt flat, in the Catamarca province, and the Antofalla Project in the Puna region; the country also has well over 60 programs in development. In the last month, two nine-figure investments have raised global awareness of Argentina as a rising power in the precious metals industry.

The first deal was announced on Dec. 22, 2021, by the Anglo-Australian company Rio Tinto, which plunked down $825 million to assume control of Rincon Mining in Argentina’s Salar de Rincon, one of the northernmost areas in Argentina’s share of the Lithium Triangle. The other investment made headlines on Jan. 2 of this year, when the South Korean steelmaker Posco invested an additional $830 million to continue expanding their lithium capabilities in Argentina’s Hombre Muerto salar after building a pilot plant there in 2016, according to “Chemical & Engineering News.”

Argentina has more than doubled its lithium production in the last decade. Current projections estimate that the country could double or even triple its production in the decade to come. Posco predicts that by 2024 the Hombre Muerto salt lake will be producing 24,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide on an annual basis. In comparison to lithium carbonate, lithium hydroxide “decomposes at a lower temperature, allowing the process of producing battery cathodes to be more sustainable and the final product to be long lasting.”

Meanwhile, the Kachi Lithium Brine Project, run by the Australian company Lake Resources in Argentina’s Salar de Carachi Pampa, recently doubled its estimate of yearly lithium production. The firm initially aimed to produce 25,500 tonnes through a definitive feasibility study, which would allow it to pursue fundraising for the project. The company recently revised its projections and is now planning to produce 50,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate per year. “We are well placed given quality resources, leading technology, and key finance partnerships to ensure an optimal set of offtake agreements that align with these expansion plans,” said Stu Crow, Chairman of Lake Resources.

The latest development in Argentina’s winning streak came when the Argentina Lithium and Energy Corporation announced that it had hired Zoppa Media Group as an investor relations consultant, according to “Yahoo! Finance.” In hiring Zoppa, Argentina Lithium has shown that they’re keen to protect their partnerships and, most importantly, the revenue they generate. Argentina now produces 10% of the lithium currently in global circulation, and they have no plans to slow down.

It will be interesting to see how Argentina deals with Rio Tinto, which lost an ongoing battle with Serbia on Jan. 20, after weeks of protests, to develop a $2.4 billion lithium project in its Jadar province. Serbian Prime Minister Ana Brnabic sided with protesters, who agreed with the group’s environmental concerns. Brnabic decisively stated: “As far as project Jadar is concerned, this is an end.” The termination of the Jadar project marks yet another instance of Rio Tinto’s well-documented history of environmental and social controversies. Despite that, Rio Tinto’s share price has seen a 16.4% gain in the first month of 2022.

Argentina’s unique political development may give it an advantage in the lithium revolution. “Peronism,” named after the hugely popular Argentine president Juan Peron, who served from 1946 to 1955 and then again from 1973 to 1974, is a brand of right-wing socialism that favors corporation-friendly economic policies alongside socialized reform for the working class. It’s a confusing ideology based primarily on staunch anti-imperialism that has drawn supporters from the far-right and the far-left. Still, it is essentially an extension of capitalism that preserves the class of elites with a strong focus on promoting working-class solidarity, despite the fact that poverty rates in Argentina have remained fairly constant at around 10-15% outside of the Argentine Great Depression.

Corporations are essentially free to profit in Argentina, with limited fear of condemnation from the general public. Despite the seemingly harmonious relationship between the elite and working classes, Peronism is regarded by many as thinly-veiled fascism. In the book “Peronism and Argentina” James P. Brennan writes, “[Former Supreme Court of Justice of Argentina Carlos] Fayt does not see anything but affinities between Peronism and fascism: their repudiation of liberalism, democracy, and Marxism; their nationalism and emphasis on a charismatic leadership, and their corporatism and stress on the values of ‘order, hierarchy, and discipline.’”

Argentine politics today are perhaps not quite as severe. Still, its current president, the center-left Peronist Alberto Fernandez, has failed to contend with dramatic increases in national poverty during the coronavirus pandemic. Argentina’s economy shrunk an estimated 12% in 2020, compared to an average of 4.4% globally. Additionally, “the poverty rate spiked to between 46% and 47% by the end of June following months of strict lockdowns to battle the spread of the virus,” according to NBC News, up from 35.5% a year prior. Although Argentina has already begun recovering, these recent developments in the lithium sector are crucial to the future of Argentina’s economy. If Fernandez’s administration fails to make meaningful progress before the end of his first term in 2023, the people of Argentina may choose to seek a change in governance.

In recent weeks, Argentina Lithium has been fervent in pursuing new contracts. On March 16th, the company acquired properties from Rincon West and Pocitos in Salta Province. Elsewhere, the American company Livent has increased its investment in Argentine lithium, with plans to triple production and build a second Argentinian mine. A March 15 update from Alpha Lithium announced that four drilling rigs would begin operating on the Tolillar Salar. The statement notes that “The four drilling rigs are focused on northern, western, and eastern extensions to the Tolillar Salar. One of the wells will be the second well into a recently discovered freshwater source, a rare and critical requirement for lithium production.”

A recent investment from South Korean company Posco, which had already invested upwards of $830 million dollars into the Hombre Muerto project, has now pledged $4 billion dollars to Argentina’s lithium. When the project is completed, Posco estimates their Hombre Muerto mine will be able to produce 100,000 tonnes of lithium per year, more than double what Australia, the world’s leading producer of lithium, was able to mine and process in 2020.

In the race to the future of renewable energy, Argentina is looking to win.