Tilsa Tsuchiya is regarded as perhaps one of the greatest Peruvian visual artists of the 20th century, receiving the prestigious Teknoquimica Prize for painting in 1970. Tsuchiya has credited her unique mytho-Surrealist aesthetic both to her education at leading art institutions in Lima and Paris and to the influence of her Japanese-Peruvian heritage.

Born the seventh of eight children in Supe, Peru, 1928, Tsuchiya was drawn to painting from a young age — later crediting her older brother Wilfredo’s interest in drawing for sparking her fascination with visual art. Tsuchiya’s father, Yoshiguro, was born in Chiba, Japan and studied in the U.S. for several years before arriving in Peru; her mother, Maria Luisa Castillo, was born at Chavin, in Peru, of both Chinese and Peruvian descent. Tsuchiya’s groundbreaking artistic career emerged directly from her experiences in Peru’s Nikkei immigrant community, which we’ll explore here.

Nikkei History

As Peru’s population of Japanese migrants, known as Nikkei, grew throughout Tsuchiya’s childhood in the 1930s, xenophobia and racial discrimination grew with them.

In 1936, Peru halted immigration from Japan after Peruvian newspapers blamed the influx of Japanese immigrants for endangering native-born Peruvians’ employment. The following year, the Peruvian government passed an executive decree that effectively stripped birthright citizenship, a right enshrined in the Peruvian constitution, from all children born to noncitizen parents. In 1940, a three-day anti-Japanese riot known as the “Saqueo” arose in Lima in response to rumors of an impending Japanese uprising, during which more than 600 Nikkei homes and businesses were destroyed, with 10 Japanese-Peruvians killed.

Following the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service’s strike on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. Office of Strategic Services — its wartime intelligence agency — identified Peru’s population of over 25,000 Japanese-Pervuians as a threat to U.S. victory in the war’s Pacific Theater. In the name of “internal security,” the Peruvian government launched a campaign of surveillance, mass arrests and deportations targeting Peru’s Nikkei communities. Blacklists of Nikkei were published in newspapers across Peru, and FBI agents from the U.S. were allowed by the local government to surveil Japanese-Peruvians. A letter by then-U.S. Ambassador to Peru, Raymond Henry Norweb, claimed that President Manuel Prado’s ultimate intentions were, in fact, “the substantial elimination of the Japanese colony in Peru.”

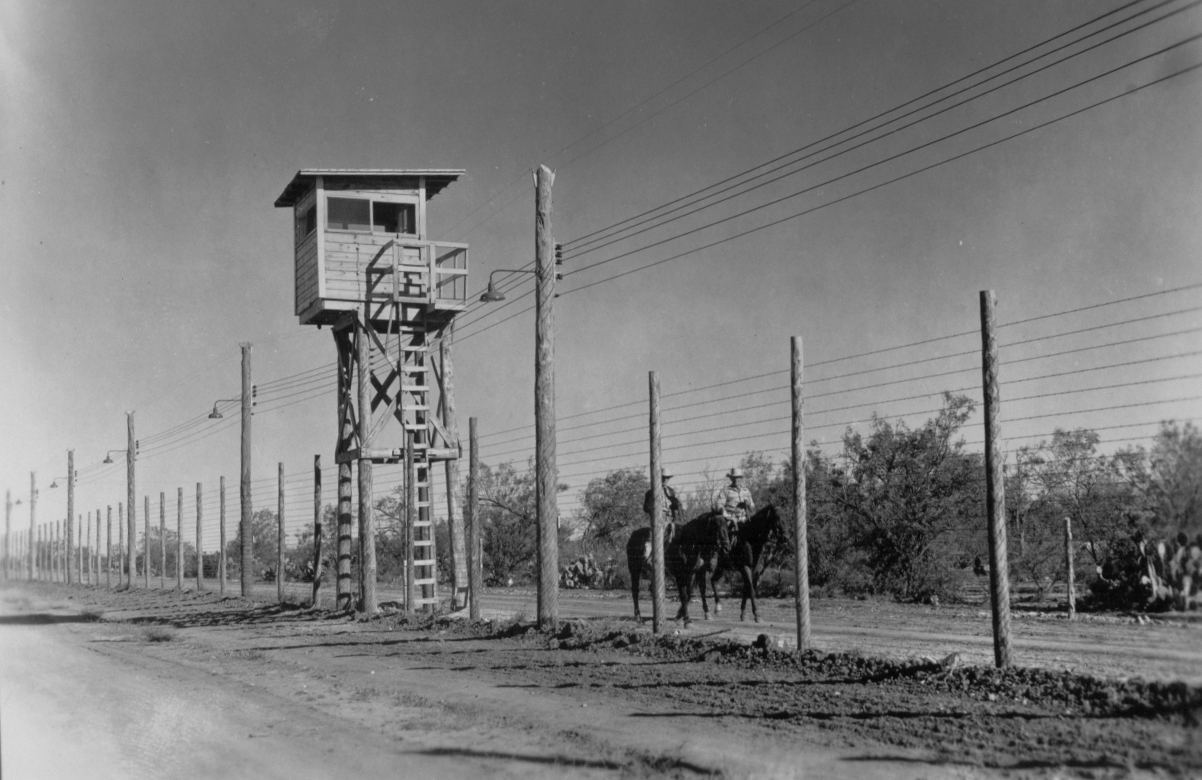

The Peruvian government began coordinating with the U.S. to transport arrested Nikkei to internment camps throughout the American Southwest. Although these arrests usually targeted men, their wives and children often accompanied deported spouses and fathers, through a process that became known as “voluntary internment.” Forcibly removed from their homes, many Japanese-Peruvians were detained alongside Japanese-Americans in Justice Department internment camps, while many others were interned in “alien detention camps” run by the U.S. Immigration and Nationalization Service in Texas and New Mexico.

Guards patrolling fence at Enemy Alien Family Internment Camp in Crystal City, Texas. Source: Texas Hill Country Trail Region.

Because the Peruvian government refused the return of Nikkei at the war’s conclusion, only 79 Japanese-Peruvians managed to re-enter Peru from the U.S., while several hundred others were deported directly to Japan. Through the efforts of American civil rights attorneys, 364 Japanese-Peruvian men, women and children secured permission to remain in the U.S. as refugees, although many found their new living conditions even more dire: the families were relocated to Seabrook Farms in New Jersey to work as laborers in company barracks. The Nikkei who successfully returned to Peru faced extreme difficulties of their own, as they, like the interned Japanese-Americans, returned to their former homes to find their assets and property expropriated. While Tsuchiya’s family was not one of the many interned in the U.S., the entire Nikkei community was devastated by the sudden loss of so many friends and neighbors. This shock undoubtedly influenced Tsuchiya’s bold choice to situate her oeuvre squarely in the heart of Peru’s cultural milieu, asserting through her choice of artistic subjects that Nikkei people like her belonged in the country despite all efforts to exclude them.

Tsuchiya in Peru

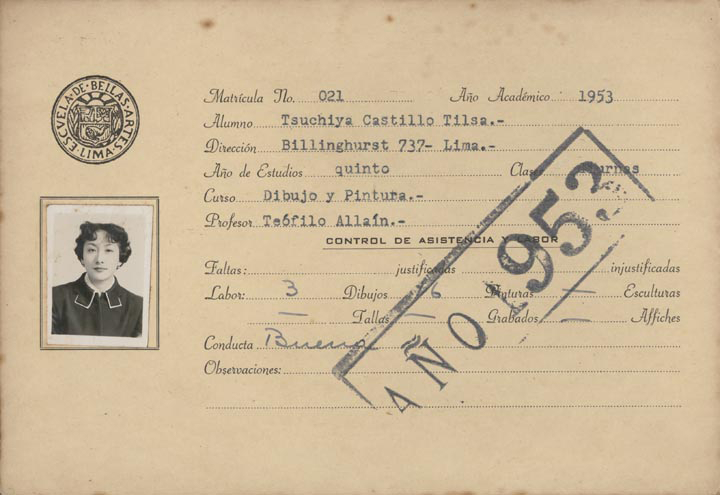

In the wake of the war, Tsuchiya began attending the Escuela Nacional Superior Autónoma de Bellas Artes del Perú (ENSABAP) in Lima, where she trained in the workshops of both Quispez Asín and Ricardo Grau and spent several years as the private student of painter Manuel Zapata Orihuela, a leader of the Peruvian indigenismo artistic movement. Orhuela’s paintings often featured flat, brightly colored and stylized Expressionist forms that drew inspiration from the region’s pre-Columbian arts, Quechua culture and Andean landscape. The influence of Tsuchiya’s several years of study with Orihuela would show in the Nikkei painter’s future works, as the Quechua aesthetic influence remained visible on her canvases throughout her career.

Ficha de estudiante de Tilsa Tsuchiya. Source: Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes

In 1949, Tsuchiya took a leave of absence from her art education following the death of her parents. She only returned to ENSABAP in 1954. When Tsuchiya graduated in 1959, she received the school’s highest honors, the Gran Medalla de Oro. The next year she traveled to Paris to continue her studies at École des Beaux-Arts. In France, Tsuchiya focused on printmaking and engraving, exploring a darker palette and minimalist aesthetic within the unique style she had cultivated alongside Orihuela.

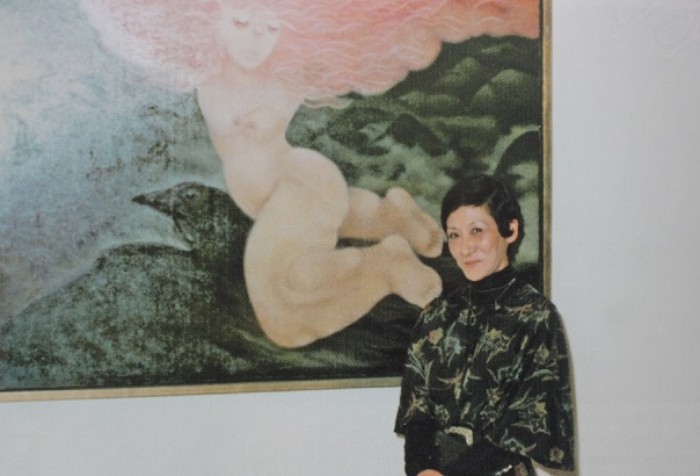

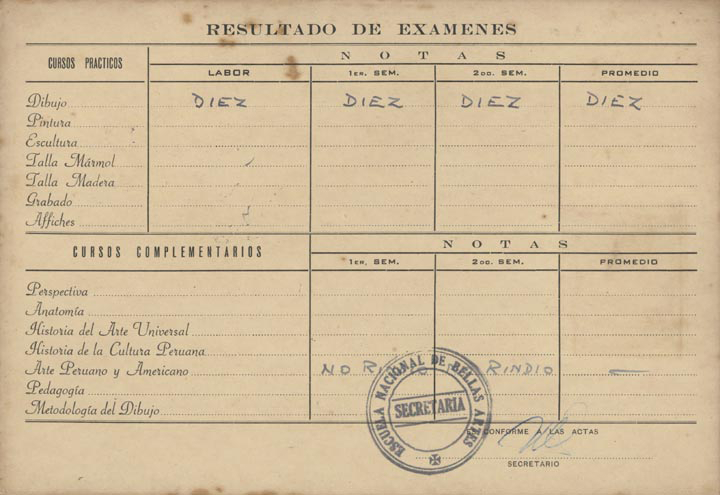

Although Tsuchiya’s first solo exhibition at the Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo in Lima came immediately after her graduation in 1959, it was her 1968 exhibition at the same museum that brought the Nikkei painter to great fame, with her dreamlike and seductive style receiving international attention. The exhibition came three years after the Peruvian government offered Japanese-Peruvians a parcel of land in central Lima for the construction of the Centro Cultural Peruano Japonés, informal compensation for their wartime persecution. Tsuchiya’s canvases, populated by surreal mythological figures and diaphanous landscapes, drew equally from Tsuchiya’s dual Japanese-Peruvian heritage and her many years’ study of European artistic traditions. They evoked the erotic and the sublime in equal measure, and raised pressing contemporary questions of gender and identity.

Ser mítico , 1971.

Tsuchiya’s Legacy

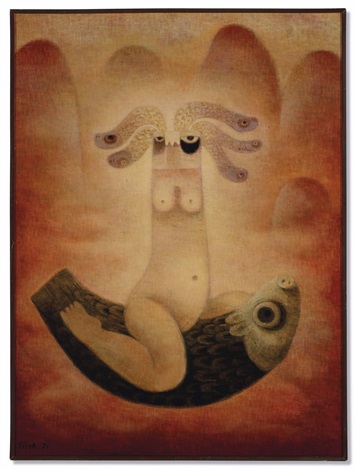

By the 1970s, Tsuchiya had cultivated a unique visual folklore that drew from Quechua, Japanese and European visual cultures, inventing her own myths and reinterpreting classical tales like Tristan and Isolde through sculpture, drawings and engravings, all newly exhibited alongside her paintings. At an exhibition in 1976 entitled Mitos, which featured a series of Tsuchiya’s works including El mito del guerrero rojo, Mito del árbol, Mito de la mujer y el vuelo, Tuschiya explained to El Comercio how her works arose in relation to indigenous storytelling traditions, naming some of the “myths” that inspired her art: the “Myth of the Lagoon,” “Myth of the Red Warrior” from Cerro de Pasco, and the “Myth of the Bird and the Stones” from Cusco. She admitted that when audiences viewed her paintings, “It’s like they are seeing inside me.”

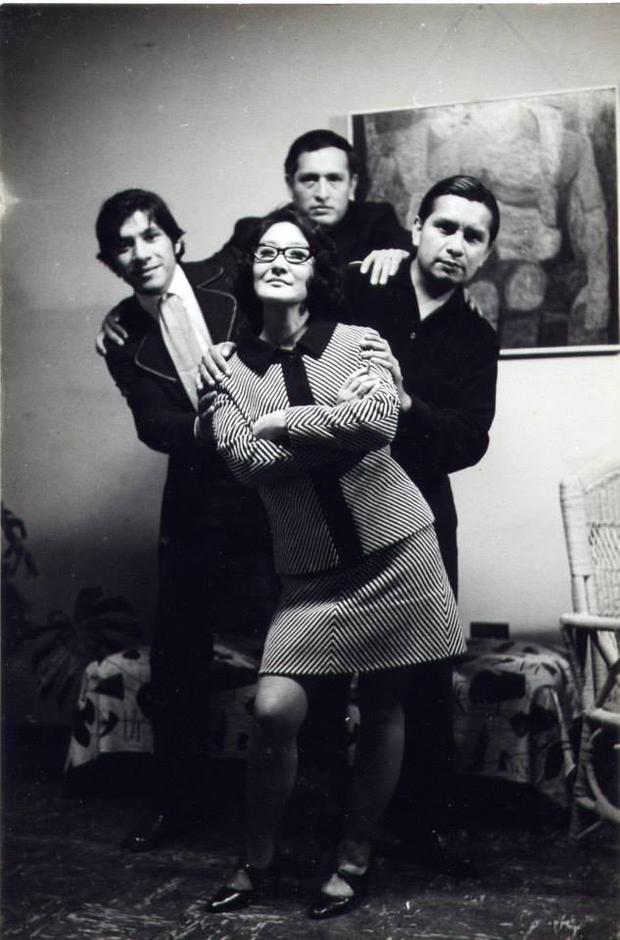

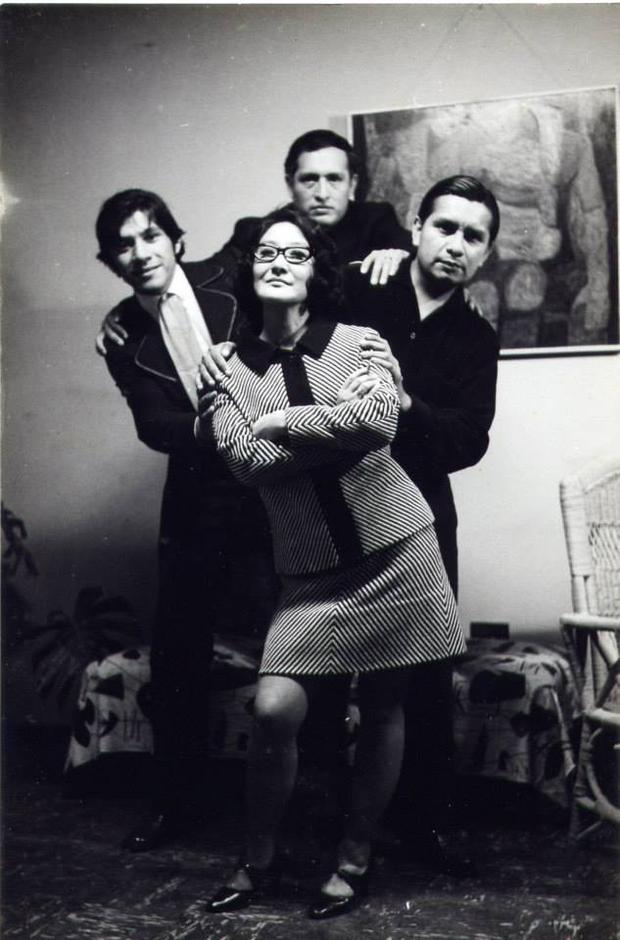

Throughout her career, Tsuchiya forged deep friendships with several poets and artists. Following her infamous 1968 exhibition, Nikkei poet José Watanabe began paying frequent visits to Tsuchiya’s studio in Breña, and Tsuchiya also developed a well-known creative bond with poet Arturo Corceura, with whom she illustrated a collection of poetry entitled Noé delirante in 1971.

Canto de paz , 1977.

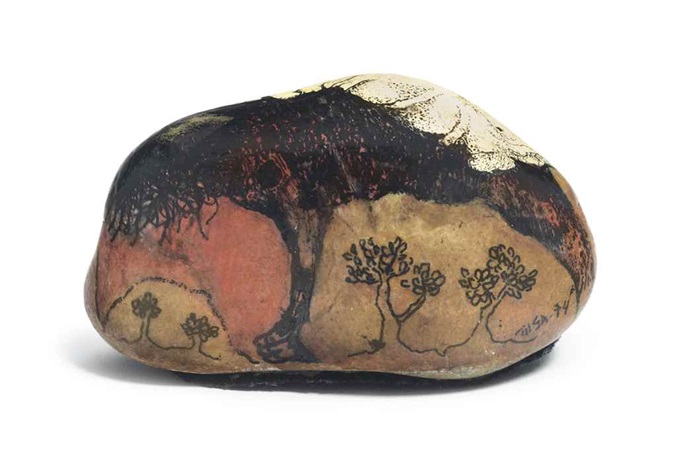

Three months before Tsuchiya’s passing in 1984, Petroperú organized the first retrospective exhibition dedicated to her career, exhibiting around 50 works Tsuchiya had produced since 1959. In the summer of 1987, Tsuchiya’s work was featured as the sole representative of Peru in Art of the Fantastic: Latin America 1920-1927, an ambitious art exhibition organized in association with that year’s Pan-American Games in Indianapolis.

In the decades since her passing, Tsuchiya’s work remains celebrated in Peru and internationally. In the international art market, Tuschiya’s works continue to fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars at auction, and in 2018, ENSABAP celebrated its centennial by posthumously awarding Tsuchiya the institution’s highest honor, la Medalla de Honor Daniel Hernandéz, in recognition of her enduring legacy in Peru’s national arts and culture.

Sin titulo , 1974.