On January 5, 2025, the eve of the Día de los Reyes—the Puerto Rican holiday also known as Three Kings Day—Bad Bunny dropped his sixth studio album, titled Debí Tirar Más Fotos (stylized as DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS).

Fans already had a series of hints about the album’s themes, including the traditional Christmas aguinaldo in its second single, “PIToRRO DE COCO,” and a Google Map/Spotify scavenger hunt leading fans around Puerto Rico to find titles of songs, to a short film starring legendary Puerto Rican actor and director Jacobo Morales. The album has quickly risen up the charts, and for the first time in history salsa and plena reached number one on Apple Music. DTMF has also received critical acclaim from publications and music critics.

As with the artist’s 2022 album Un Verano Sin Ti, many reviews have referred to DTMF as a “love letter” to Puerto Rico, but labeling this album a mere love letter massively oversimplifies what Bad Bunny is doing here. This album is a warning to all Puerto Ricans—both those residing in Puerto Rico and in the diaspora—about the state of their “archipélago perfecto” (as he refers to Puerto Rico in the album’s closing track “LA MuDANZA”), and a rallying cry to address the myriad crises facing their homeland.

Many reviewers have pointed out the album’s fusion of reggaetón with more traditional Puerto Rican rhythms like plena (showcased in “DtMF” and “CAFé CON RON”) and 1970s salsa (as heard in “BAILE INoLVIDABLE” and “LA MuDANZA”). Bad Bunny has always blended genres with reggaetón, but the more traditional Puerto Rican music here is notable and a testament to the flexibility of the artist along with his longtime producers Tainy, MAG, and La Paciencia. The album draws from the long history of Puerto Rican music-making as a form of resistance, particularly against U.S. colonialism, and the use of art and dance to tell stories of everyday Puerto Rican life, joy, and struggle.

But the Puerto Ricanness of this album extends far beyond the rhythms. DTMF, as well as the media that accompany it, highlights how the most basic elements of Puerto Rican life and identity are rapidly changing and, in some cases, even disappearing. Since their country became a colony of the U.S. in 1898, Puerto Ricans have spent the past 126 years enduring everything from forced sterilization and labor exploitation to the U.S. military’s decades-long practice of testing bombs on Puerto Rican lands. Over the past 20-plus years, a devastating debt crisis has had disastrous effects on public education, health care, infrastructure, and more. These problems were only compounded in 2017 when Hurricane María decimated Puerto Rico, leaving many Puerto Ricans without power for almost a year and killing at least 4,645 people. Both the U.S. and Puerto Rican governments have responded with increasingly harsh austerity measures, as well as the implementation of various tax incentives in an effort to lure wealthy Americans to the archipelago. Simultaneously, Puerto Ricans have migrated to the United States—as they have done for more than a century—in search of better opportunities.

Activists have organized against gentrification, privatization, and displacement for years. Bad Bunny already addressed these issues in what many have considered his most political song “El Apagón” (until DTMF came along), which included a 20-minute documentary about these issues in its music video. But in DTMF, the message is more clear than ever before—his lyrics celebrate Puerto Rico as the most beautiful, wonderful place on the earth, and they also warn that everything that makes it special is at risk.

This is perhaps best exemplified by the symbol of the sapo concho, the endangered crested toad native to Puerto Rico, which appeared in many of the teasers for DTMF, including the short film that Bad Bunny released just days before the album. Sadly, invasive species of foreign toads and the destruction of its natural habitat due to land development has pushed the sapo concho to the brink of extinction—and, suddenly, the link between the existential threat toward this small creature’s existence and the album’s political and cultural commentary becomes crystal clear. In the short film, actor Jacobo Morales walks to buy food for himself and his friend Concho at a local bakery—a pursuit that takes him past homes occupied by Americans playing loud rock and country music, in contrast to the reggaetón that once filled the air. There, Morales encounters an English-speaking cashier who offers him strange versions of Puerto Rican food, most notably a traditional quesito (a cheese-filled puff pastry) without the cheese. In a poignant moment, a young Puerto Rican man pays for Morales, who does not have a phone to use at the newly cashless bakery. “Seguimos aquí,” he tells Morales. We’re still here. Just like the endangered sapo concho, what is at stake is the loss of not just Puerto Rican culture, but Puerto Rico as a whole. Puerto Ricans must continue to fight for their culture and their community.

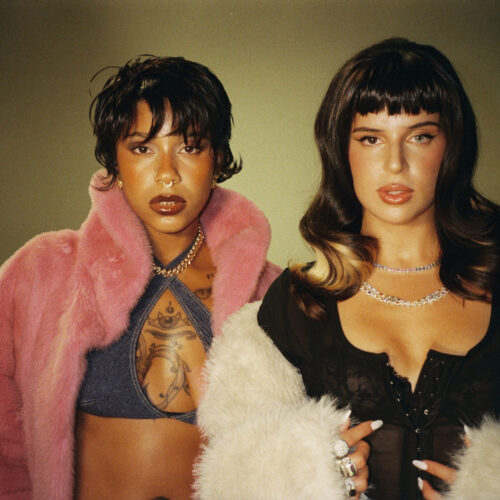

Image courtesy of artist.

While virtually every song addresses this theme, perhaps none does so as well as “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii,” which translates to “what happened to Hawaii.” The slow, haunting song warns Puerto Ricans that their land, their culture, their very existence might disappear. Like Puerto Rico, the U.S. acquired Hawaii in 1898. Despite receiving its status as a state in 1959, Hawaii faces many of the same issues as Puerto Rico, including wealthy Americans taking over Indigenous Hawaiian lands, often through illegal means, and the decimation of Hawaiian culture. In his song, Bad Bunny warns, “They want to take my river, and also the beach/they want my neighborhood, and for my grandmother to leave.” He implores Puerto Ricans to hold onto their flag and their culture. To hammer these messages home, the artist released a series of visualizers for the album on YouTube with text written by Puerto Rican historian Jorell Meléndez-Badillo detailing histories of Puerto Rican resistance and US colonialism on the archipelago.

DTMF thus paints a bleak portrait of Puerto Rico’s present and future if things do not radically change, and soon. Nevertheless, it also offers a message of hope. In addition to collaborating with up-and-coming Puerto Rican stars, including RaiNao and Dei V, Bad Bunny worked with young people from Puerto Rico’s Escuela Libre de la Música, a music-focused school for middle and high school students. These young people are the future of Puerto Rican music—both in shaping where it will go and in keeping its musical traditions alive. Consequently, Bad Bunny told the New York Times that these students worked on the salsa songs for DTMF. The album’s final song, “LA MuDANZA,” is a salsa that ends with the triumphant refrain, “Yo soy de P FKN R”—a line that references one of Bad Bunny’s first anthems of Puerto Rican pride “P FKN R.”

In that same song, Bad Bunny declares that they should “play my song on the day they bring back Hostos,” referring to Eugenio María de Hostos, a 19th century Puerto Rican intellectual and independence activist. Having died in 1903, Hostos is interred in the Dominican Republic, where he said he wanted his remains to stay until Puerto Rico gained independence. By referencing the return of Hostos, Bad Bunny provides a direct challenge to Puerto Rico’s colonial status and the problems it has wrought for residents. Ultimately, though, it offers a glimmer of hope: a call to imagine a different kind of future. So, yes: DTMF is a love letter, but it is much more than that. Though it is cautious, tender, and nostalgic, it is also a bold warning—and a rallying cry.

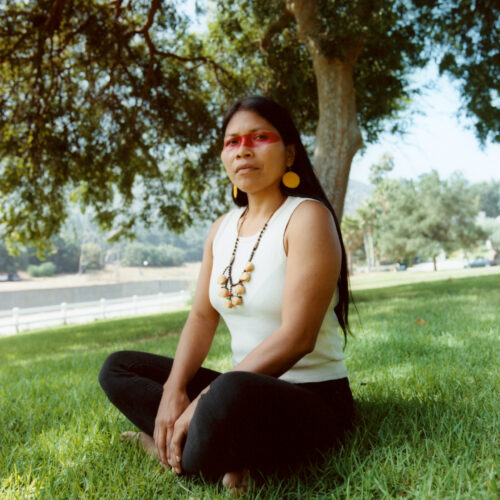

Vanessa Díaz is an Associate Professor Chicana/o and Latina/o Studies at Loyola Marymount University. Petra Rivera-Rideau is an Associate Professor of American Studies at Wellesley College. Díaz and Rivera-Rideau both teach courses about Bad Bunny at their universities and they are the co-founders of the Bad Bunny Syllabus Project.