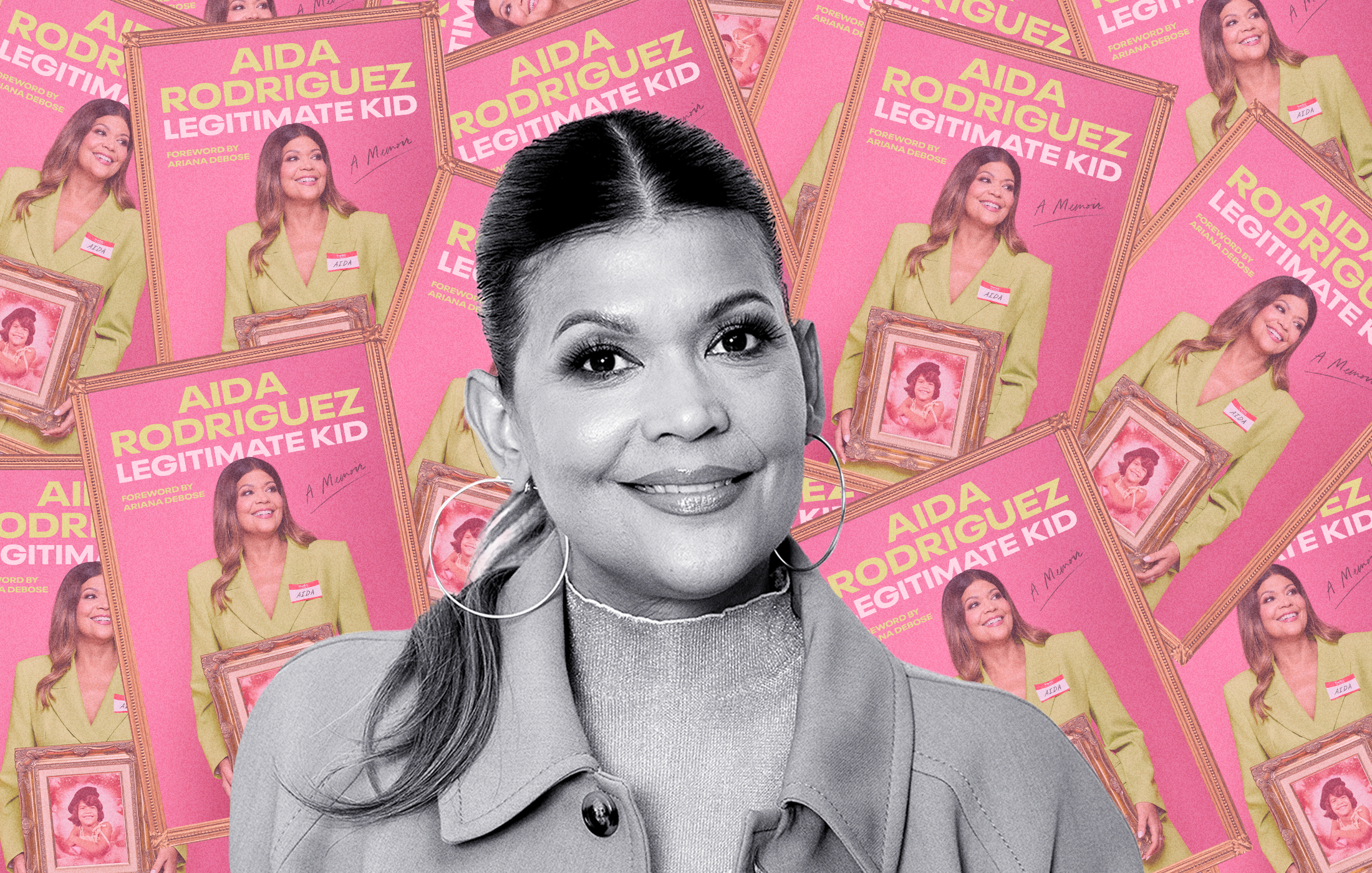

Nothing breeds comedy better than adversity. Making it to the top often means digging yourself out of the hole. The deeper the hole, the longer the climb, and the stronger you are when you finally make it out. Very few comedians have had to follow the light quite like Aida Rodriguez, a Puerto Rican and Dominican comedian who, at 46, released her first memoir, “Legitimate Kid,” just two years after Max debuted her comedy special, “Fighting Words.” Prior to that, Rodriguez made an impression on NBC’s “Last Comic Standing,” where she placed ninth out of a total of 100 up-and-coming comics.

When LATINA spoke with Rodriguez, she explained that her time in the comedy scene hasn’t just made her a better joke-writer or given her more confidence on stage. “One of the things I’ve learned,” she said, “is that a lot of these people have no idea what they’re doing.” Even now, comedians are still lunging for the low-hanging Latin fruit, like jokes about the “Fast and Furious” movies that were already out-of-date more than a decade ago. “The importance of understanding that they have no clue what’s going on is an opportunity for us to step in there and really tell our own stories,” she said.

If Latinos are frustrated with how they’re portrayed in pop culture, which many of them are, it’s because there aren’t enough of them actually writing the jokes and stories we see on-screen. “The business doesn’t know us in the way that we know us and we get so angry because they don’t,” she said, noting that she is determined to be part of the solution. “I wanted to be of service so that I could initiate some change because we’re not going to burn it down,” she said, adding, “Not yet.”

That also means getting oldheads like George Lopez on board to work on shepherding the younger generation to stardom. Fans of either him or young Latino comedian Ralph Barbosa might remember their beef from earlier this year, when Lopez said he wasn’t going to extend a hand to Barbosa because nobody did it for him. The cruel irony of it all is that Lopez owes part of his career to a similar story between him and Erik Estrada, who did the same thing to Lopez when he was still on the rise.

“There’s an education that needs to take place,” Rodriguez explained, “because the problem is that a lot of Latine people, when they ascend and they have power, they turn around and start doing to us what the white people have been doing.” Because diversity in the entertainment industry means occupying a seemingly finite number of “slots” in mainstream showbusiness, Rodriguez pointed out how established Latine comedians “don’t want us to take what they have or what they think is theirs.”

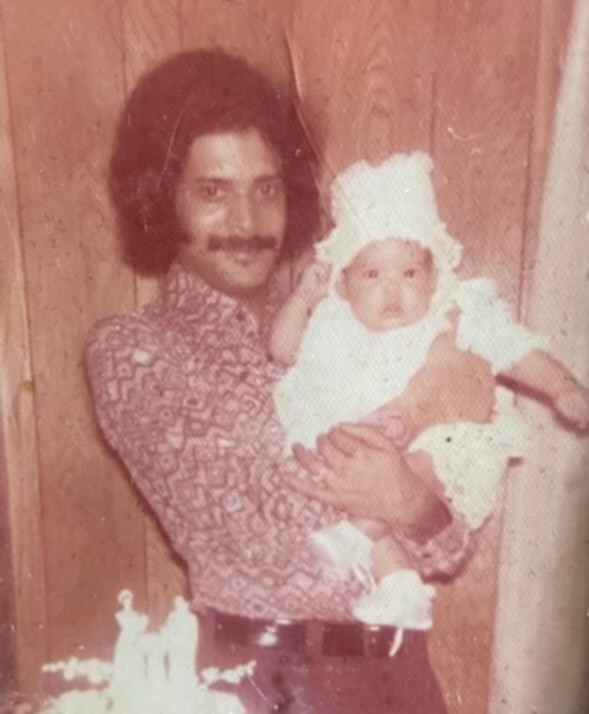

For Rodriguez, the answer was vulnerability. Where most comedy specials end with “the big joke,” Rodriguez ended hers with a short documentary about meeting her father for the first time in the Dominican Republic. “I really wanted people to see how we mine our jokes,” she said. “Specifically, those comedians who talk about family stuff and how we get to the point where those experiences become jokes.” The comedian described it as “a therapeutic process” that allows comics to process their own trauma.

Aida and her father Maximo Paradas. Courtesy of Aida Rodriguez.

Rodriguez considers herself to be a very private person. She also knew that, as a rising comedian whose entire ethos revolves around bringing genuine Latine experiences to light, she was obligated to open “one of [her] greatest wounds” for the sake of connecting with viewers who may have a similar story to tell. “I really wanted all the little children who are experiencing that, what I was experiencing when I was a kid, to see something that lets them know that they’re okay and they’re going to be okay,” she said.

Like many bright-eyed hopefuls who travel to LA in search of stardom, Rodriguez aspired to break into the business as an actor. However, she quickly realized that women who looked, talked, and acted like her weren’t exactly a hot commodity. In order to create her own roadmap to success, Rodriguez had to look back at what made her want to be an entertainer in the first place – comedy. “I’ve always admired stand-up comedy since I was a kid,” she said. “Richard Pryor was my hero. I just remember listening to him [as a kid] and saying, ‘I want to do that.’”

If there is one ambition that Rodriguez has carried with her for her entire life, it is to be funny. She explained how, when she watched Johnny Carson as a kid, “I would grab the broomstick and say, ‘I’m going to do that one day.’” Still, she faced pressure to redirect her trajectory in life. “[I was] told that [comedy is] not a feminine thing, especially being Latina, being told men don’t want a goofy wife,” she explained. Still, her days of holding the broomstick in her family’s living room came full circle. After struggling as an actor and, at one point, living in her car with her two children, Rodriguez looked to stand-up, her first love, as a way out.

Aida with her daughter Akaylah and son Omar after Last Comic Standing taping. Courtesy of Aida Rodriguez.

However, as an older Latina Rodriguez found that she needed to work twice as hard to get half as far as some of her contemporaries. “I wanted to talk about being a brown woman who’s not 20, and explore the ageism and sexism that I experienced,” she explained. “I don’t want to do tropes. I don’t want to perpetuate the stereotypes. I want to find the way in, to tell that story in a way that resonates and that’s clever.” Eventually, the stories behind the jokes became as relevant to Rodriguez’s career as the jokes themselves.

In the process of writing her next special, Rodriguez wrote a memoir which distinguishes itself from her material — it’s not particularly funny. “The thing about a joke is the joke has a certain rhythm. There’s a structure to the joke. It also has an allotted time,” she said. “There are a lot of times where, when you tell a joke, people love the joke. They love that bit for a moment. But I like to tell the story behind it, underneath it, where it comes from.” Naturally, she jumped at the opportunity to put some of those stories on the page.

“I don’t have punchlines in the book. I wrote it just as a literary piece separate from my comedy and I invite people who want to see me be funny to come see me on stage.” The book, however, is an earnest attempt to tell her life story without the added pressure of adding a comedic spin to everything. That said, fans of Rodriguez’s comedy should expect some new material in the near future, including a potential TV show that the comedian has been shopping around Hollywood for the last few years.

“I’ve been working on [the show] for seven years,” she said. “Three production companies and two networks later, I’m in development now.” As someone who is hellbent on bucking stereotypes whenever and wherever possible, Rodriguez’s motivation behind the series is, like her comedy, rooted in honesty. “I just really want to do a show so people can see the world that we come from. And I don’t want to specifically make it [a Puerto Rican-Dominican show].” Rodriguez thinks that, in an attempt to distinguish each Latin American culture as an independent entity, “The colonization rains down on us and now we have remnants of that in the way we interact with each other.”

To hear Rodriguez say it, Latin Americans are definitely not a monolith, but there are commonalities among all of us worth exploring. “We’re magic across the board, from the Caribbean to Central America to South America to here in North America,” she said. “We are magic and we are the wildest dreams of our ancestors. And I just want to be able to tell those stories.”

Josef Rodriguez is a writer, filmmaker, and film critic living in New York City.