LATINA is highlighting the work of Latinx creatives and visual artists through our column, Curated by KCV. Each month, Art Curator and Processa founder, Kiara Cristina Ventura, will speak on exhibitions and inspirational artists within the Latino community.

When I walked into the Domesticanx exhibition at New York City’s El Museo Del Barrio, I immediately felt like I was in my abuela’s house. I could smell the fresh cafe bustelo brewing in the greca, the pungent Agua Florida emerging from the altar, and the fresh coat of fabuloso permeating the air.

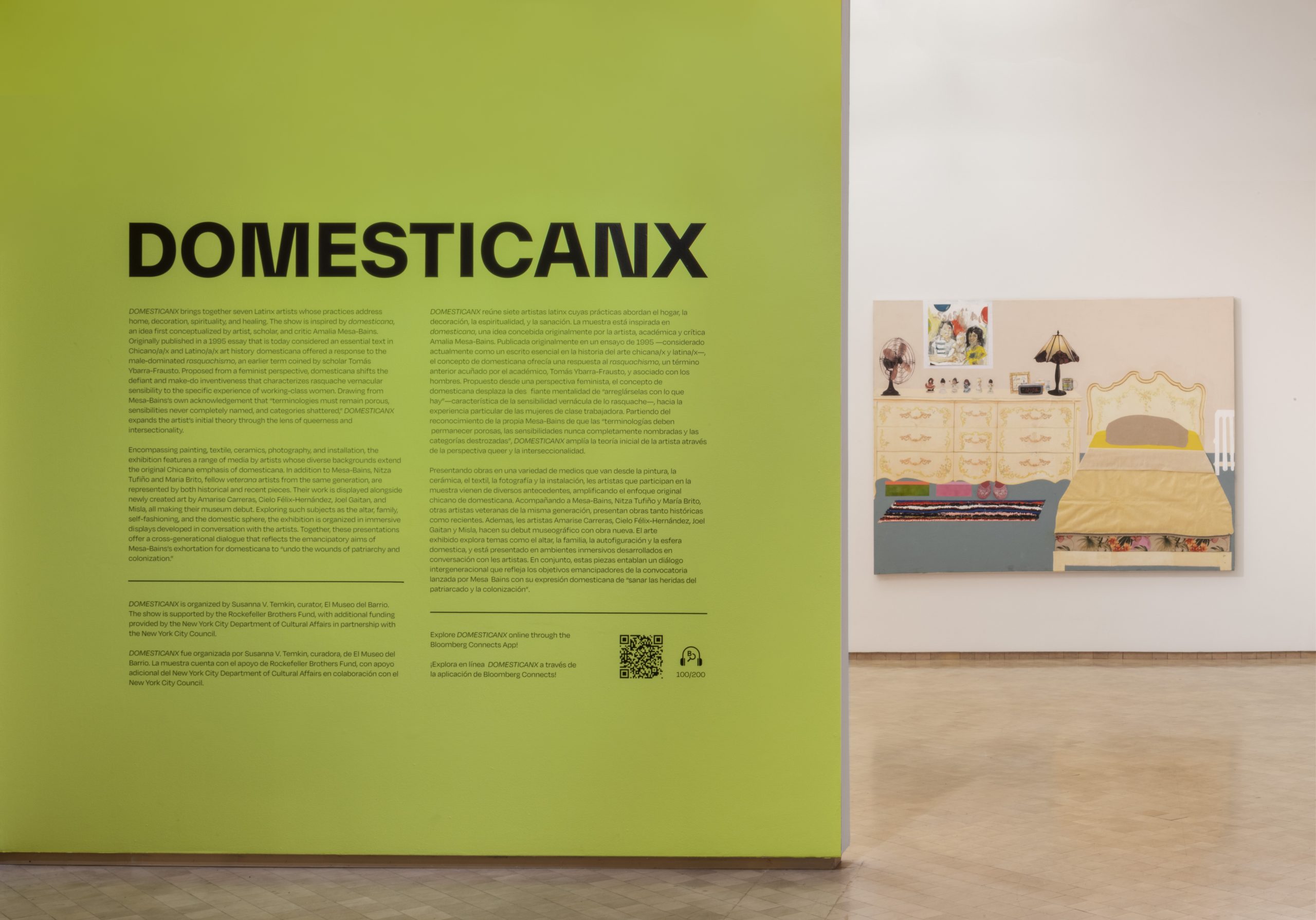

El Museo Del Barrio’s curator Susanna Temkin tells LATINA, “The show is inspired by the concept of ‘domesticana,’ first theorized by artist, scholar, and critic Amalia Mesa-Bains in the 1990s.” Domesticana is related to the term Rasquachismo, coined by scholar Tomas Ybarra- Frausto, used to describe aesthetics present in the working class Chicano art and Mexican art movements that “make the most from the least.” Bains describes the term as “aesthetic expression [that] comes from discards, fragments, even recycled everyday materials…. The capacity to hold life together with bits of string, old coffee cans, and broken mirrors in a dazzling gesture of aesthetic bravado is at the heart of rasquachismo.” Domesticana derives from rasquachismo but uses a feminist lens, drawing from feminine elements that are tied to cultural memory.

Domesticana reminds me of the many Latinx artists making work inspired by the ways the women in their life navigate their identities and their households. How have our mami’s and abuela’s inspired us? And which domestic everyday practices or crafts have they passed down? These connective moments now live in our collective cultural memory.

Curator Susanna Temkin centers the work of Amalia Mesa-Bains as a foundational point of reference throughout El Museo Del Barrio’s exhibition to highlight the relationship between femininity and domestic space. Yet she expands these themes beyond Chicana culture and relates them to queerness and other intersectional identities within the Latinx diaspora. “Bringing up ideas of spirituality and centering queerness in discussions of Latinx art…these are really critical conversations that I am glad to be able to center,” notes Temkin.

Domesticanx powerfully shows a younger, emerging generation of artists alongside veteran Latina artists, which include Amalia Mesa-Bains, Nitza Tufiño and Maria Brito. Temkin calls Mesa-Bains the madrina (godmother) of the exhibition, in fact, she even received the blessing to pursue this show from Mesa-Bains herself.

Amalia Mesa-Bains “Museum of Fatima”

Mesa-Bains is known for her art historical essays and artworks by creating “altar installations,” a form of multimedia work she pioneered in the 1970s. Her works based on home altars and ofrendas (offerings) speak to sacred spaces, memory, life and death, the mystical and mythological. Her piece Museum of Fatima (1995/2022) connects the gallery spaces of Domesticanx and blesses the show with its maternal energy. At its center, an intricately beaded sculpture sits adorned with a seashell and white flowers. Inside of the sculpture stands a figurine of a nun with a rosary in her hands and a soft facial expression.

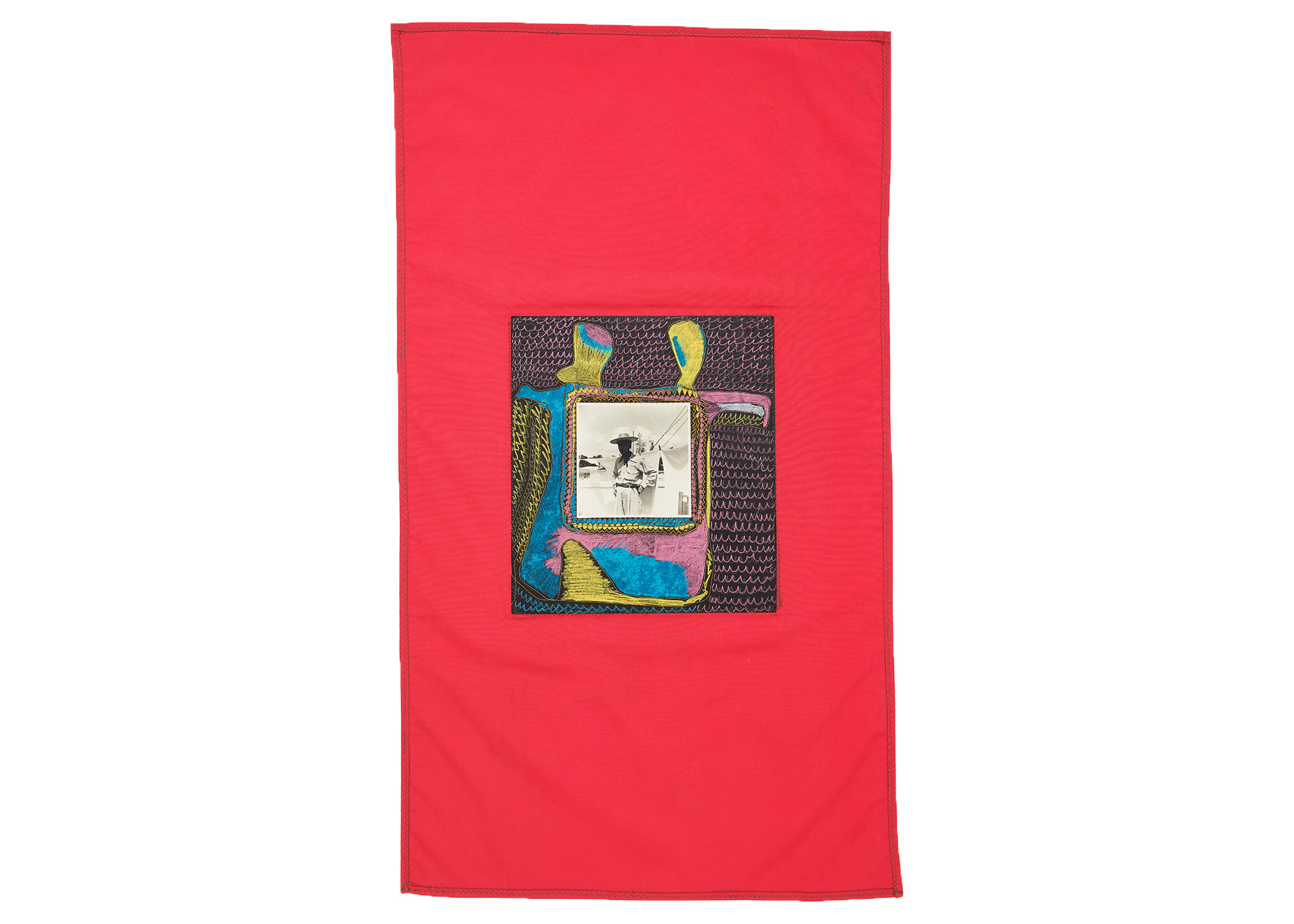

- Nitza Tufiño, “Homenaje Tenderete #3” (back), 1979-80, yellow cloth, thread, paper, vintage photographs, Prismacolor wax pencil, 37 x 21 in

- Nitza Tufiño, Homenaje Tenderete #4 (back), 1979-80, yellow cloth, thread, paper, vintage photographs, Prismacolor wax pencil

The exhibition also features an installation of textile works made in 1979-80 by Mexican Puerto Rican artist, Nitza Tufiño, hanging on a clothesline, directly portraying domesticity and home labor. Each textile draws us in with a vintage black and white family photograph, framed with colorful wax pencil designs.

Maria Brito, “Come Play With Us – Childhood Memories” 1985, mixed media, 80 x 48 x 53 in

In contradiction with the warmness of many of the works in the show, Cuban-American artist Maria Brito conveys coldness with her sculptures. Come Play With Us: Childhood Memories (1985) represents notions of surveillance and escape, as it incorporates a nursery, detached baby hands, and mirrors, hinting to the ominous side of labor, and traditional yet restricted gender roles in domestic spaces.

Amarise Carreras. “Her winds and tides bring future homes.” 40 x 36 in

In addition to the above mentioned veteran artists, this exhibition features a younger generation. The exhibition opens with Boricua artist Amarise Carreras’ photo based works. I was immediately drawn in by Her winds and tides bring future homes (2022), a photo of an altar made up of seashells, leaves, flower petals, Agua Florida, satin and marbles; A hand squeezes an orange as if the juices are blessing the altar with sweetness. The physical work is framed by a reclaimed door frame and shiny oyster shells, creating a beautiful balance between organic material and the photo print. I couldn’t help but think of legacy, hence the name of the piece, and how maternal figures pray and set intentions for the future generations to come.

Misla, “Cuarto,” 2019, mixed media, 70 x 96 in

Nuyorican artist Misla’s collage and mixed media work Cuarto (2019) depicts a bedroom space. My favorite moments in this piece are the pink Chinese chanclas and the Precious Moments figurines that take center stage on the bureau. In the painting we see a room that encapsulates the abuelita aesthetic and functions as a figure-less portrait of a maternal figure. The work led me to think about how one’s room also serves as a physical representation of a person and how each of their possessions carries their energy. The familiar elements of the piece made me feel as if I had been in this room before.

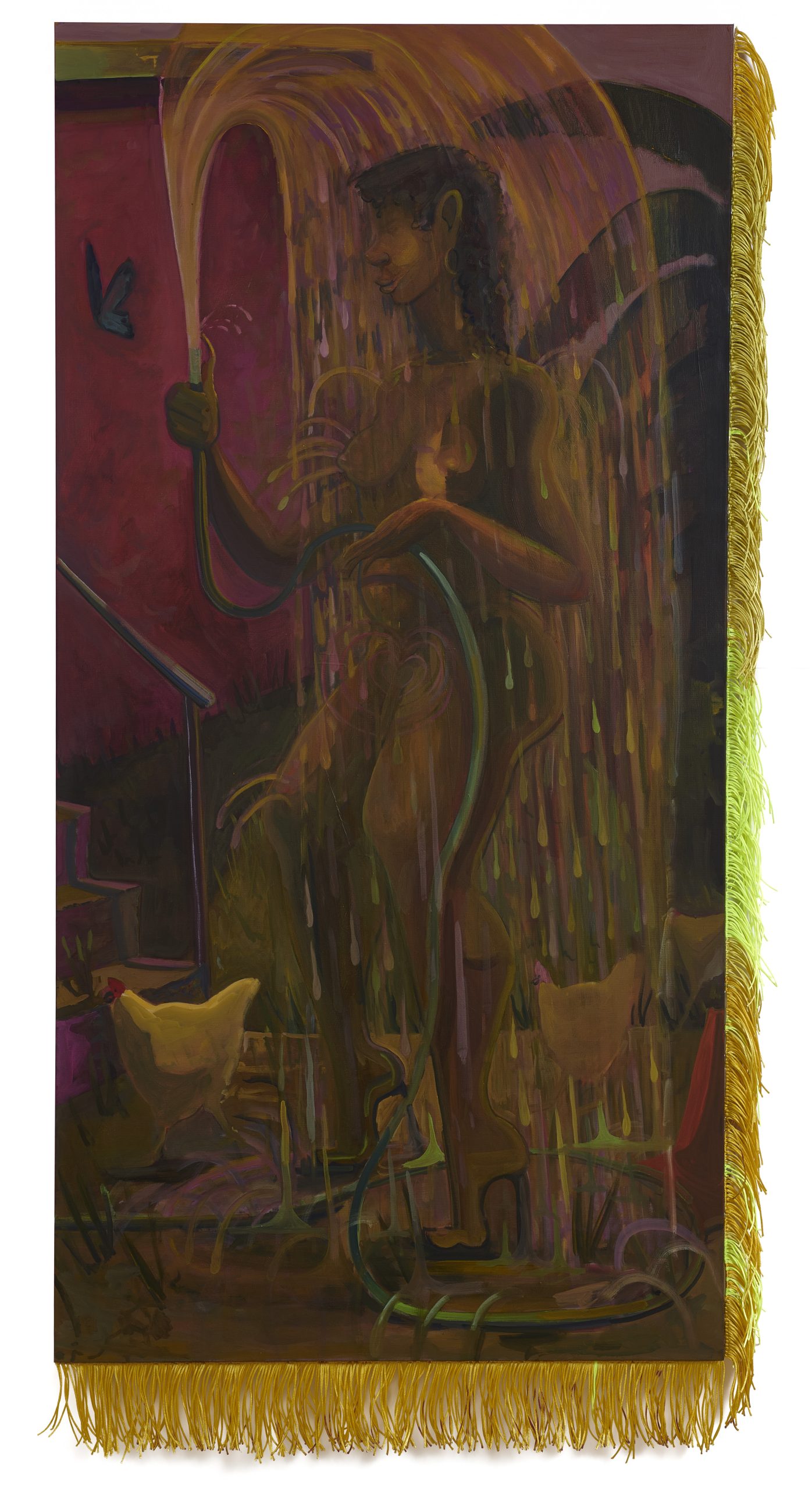

- Cielo Felix Hernandez, “Only A Mirage,” 2022, oil on canvas

- Cielo Felix Hernandez, “Ácido Sabor,” 2022, oil on canvas, 41 x 29 x 1 1.2 in

In her paintings, Cielo Félix-Hernandez draws on memory and aesthetics derived from cultural legacy to reflect her lived experience as a trans-femme Boricua. Here she presents paintings of scenes of a nude feminine figure in a tropical space. We see a story unfold between the figure and the free range chickens frolicking in her finca (farm). Throughout the paintings are motifs symbolizing love and freedom, such as hearts, butterflies, and forms of water. She paints a space that feels like an in between of a sort of utopia and reality. The femme figure seems comfortably nude in the paintings, sending a radical message about femininity in relation to safety, rest, and relaxation.

- Joel Gaitan, “La Florcy,” 2022, terracotta and gold

- Joel Gaitan

Nicaraguan artist Joel Gaitan’s terracotta vessels fill the exhibition with so much life as each piece is personified with a face and shows a spectrum of emotive facial expressions along with their own individual essence. Inspired by Gaitan’s Nicaraguan heritage and referencing early Mesoamerican objects, the vessels’ voluptuous forms are adorned with braids, animal motifs, piercings, and shiny gold teeth. In conversation with spirituality as the artist makes each piece as offering to their ancestor. Gaitan also speaks to sexuality and queerness as some of the pieces have aroused genitals and both masculine and feminine features. Thus, loudly challenging the taboos on gender, pleasure, sexuality with the decolonial act of honoring queerness that has always been embedded in indigenous ways of being.

The art presented in Domesticanx breaks the shackles of traditional gender roles in the home, and reclaims inherited practices related to femininity as acts of self-care with power and agency. On what Temkin hopes people take away from this exhibition, she shares, “I hope people recognize the domesticana aspects in their own life. I really want to center the artist’s voice. The work represents an anti-patriarchal, anti-colonial stance. I want the visitors to walk away knowing that.”

Domesticanx is on view at El Museo del Barrio through March 26, 2023. More info here.