Long pants, high socks, long sleeves, hats, bandanas. Surgical tape wraps around the thumb, middle finger, index finger to protect blistered hands; gloves are too bulky for picking cherries. A howling Washington wind stirs dust around the field, distant chatter and laughter hanging low like morning dew. Farm workers bend, reach, collect. Behind a white picket fence, it would be called harvesting, but under the hot Washington sun, it’s called picking. The massive corporations that operate here see profits by the minute — one worker envisioned charcoal outlines, figures, portraits on a canvas.

Narsiso Martinez was a student at California State University earning his BFA in painting. Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, Martinez immigrated to the U.S. with his family when he was 20. He worked with them in the agricultural fields of Washington state every season during his undergraduate studies, and again for three years afterward to fund his MFA. Today, Martinez is an established fine artist who was recently awarded the 2023 Frieze Impact Award and has exhibited in prestigious galleries around the world, including the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Now, he aims to invest in pathways for migrant farm workers in the U.S. to get an education. “There was a lot of cheering for farm workers during the pandemic. Now that it’s ‘over,’ I feel like nothing has changed, at least legislatively. Farm workers are still in the same position. There’s still a lack of opportunities… One of the solutions is to make sure that kids can go to school. I think that’s a way out.”

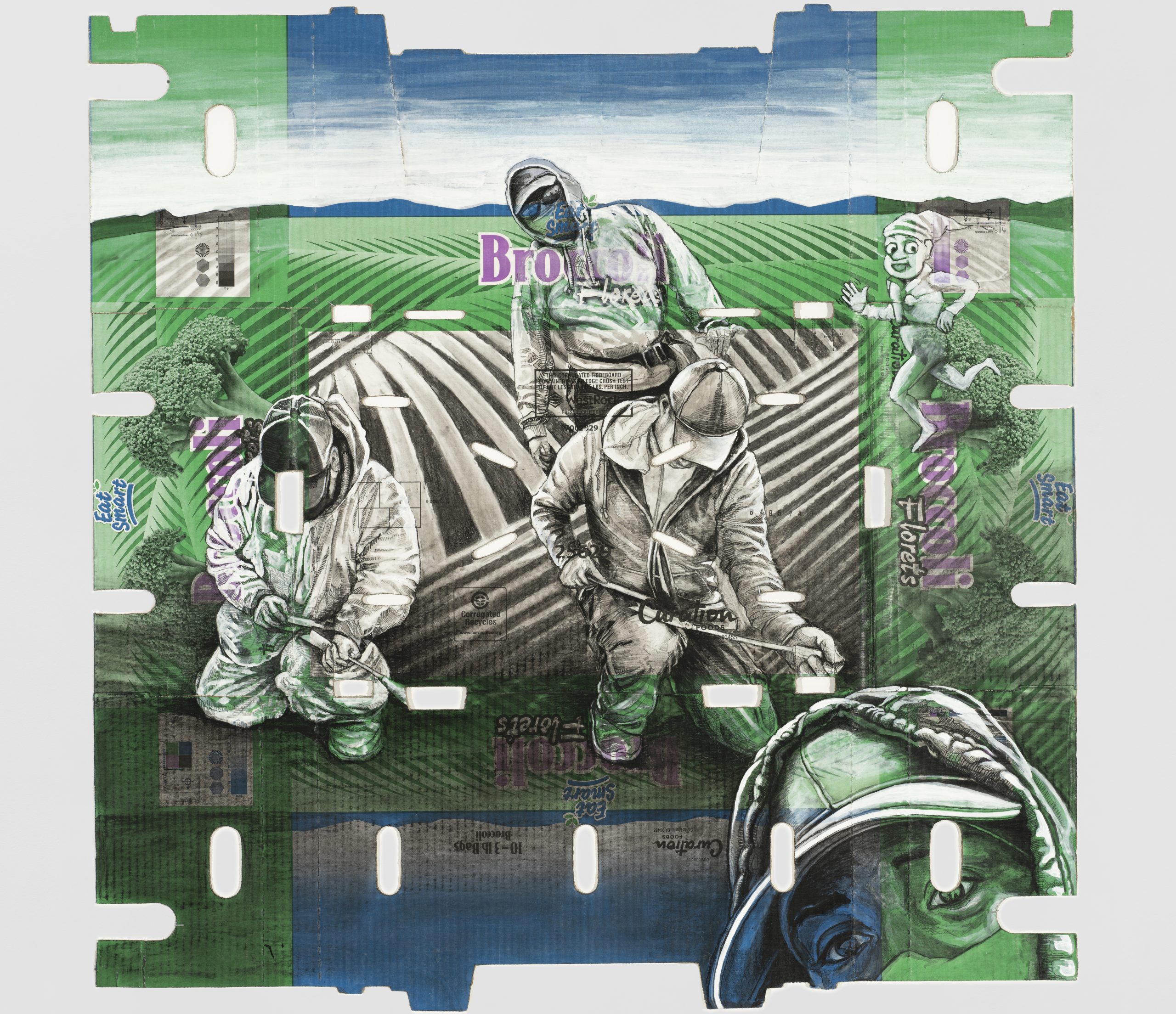

Self-Portrait En La Cherry (with Strawberry Fields in the Background) (2020). Ink, Charcoal, Gouache and Matte Gel on Produce Cardboard boxes. 53 x 72 Inches. Photo Credit: David Lah. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

It’s a tricky line to tow – that of an artist making politically charged art for the “white cube” gallery world, long argued to be oppressively purist. Perhaps initially following the cues of the fine art world, Martinez began with traditional oil on canvas during his studies, where he attempted to illustrate the tensions between the wealthy and working class in the context of agribusiness. “I was literally painting men with suits and luxurious houses.” But it wasn’t working, he tells LATINA over Zoom, “I was trying too hard, I guess.”

These early works would garner harsh critiques from his peers, mostly on technique. “They would be like, ‘oh, I think those colors are wrong,’ or, ‘your proportions are off.’ It was all about technicality, and it was frustrating.” Martinez realized that he needed to create something new within the painting, something that would make people see beyond the brushstrokes.

One day, during one of his summers working in the fields, Martinez’s sister came home from Costco with a trunk full of groceries packed in colorful produce boxes. It was then that Martinez realized how he could illustrate the oppressor in his story — by not painting them at all.

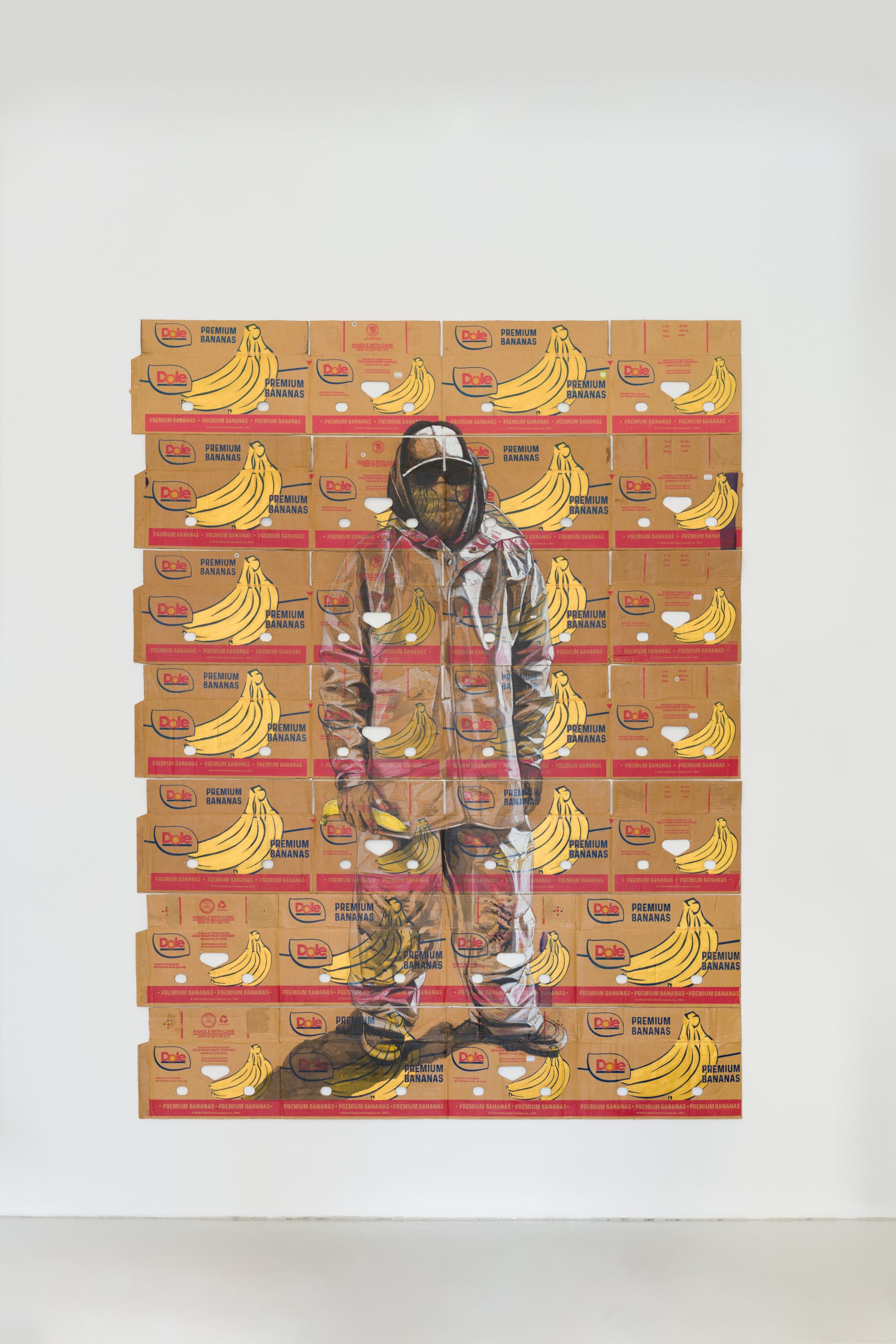

Banana Man (2021) ink, gouache, charcoal, and collage on produce cardboard boxes. 93.5 x 72 inches. Photo Credit: Yubo Dong / ofstudio. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

“By drawing farm workers on the [produce] boxes, I didn’t have to worry about representing the wealthy because they were [already] represented by the labels and the logos. I could overlap [the labels] with my drawings. That created a conversation that I think was key, or that I understood.”

Martinez now exclusively uses produce boxes as his canvases, drawing on them directly with charcoal, guache, and more frequently — as in the case of his largest work, the Rivera-esque mural “Legal Tender” — gold leaf.

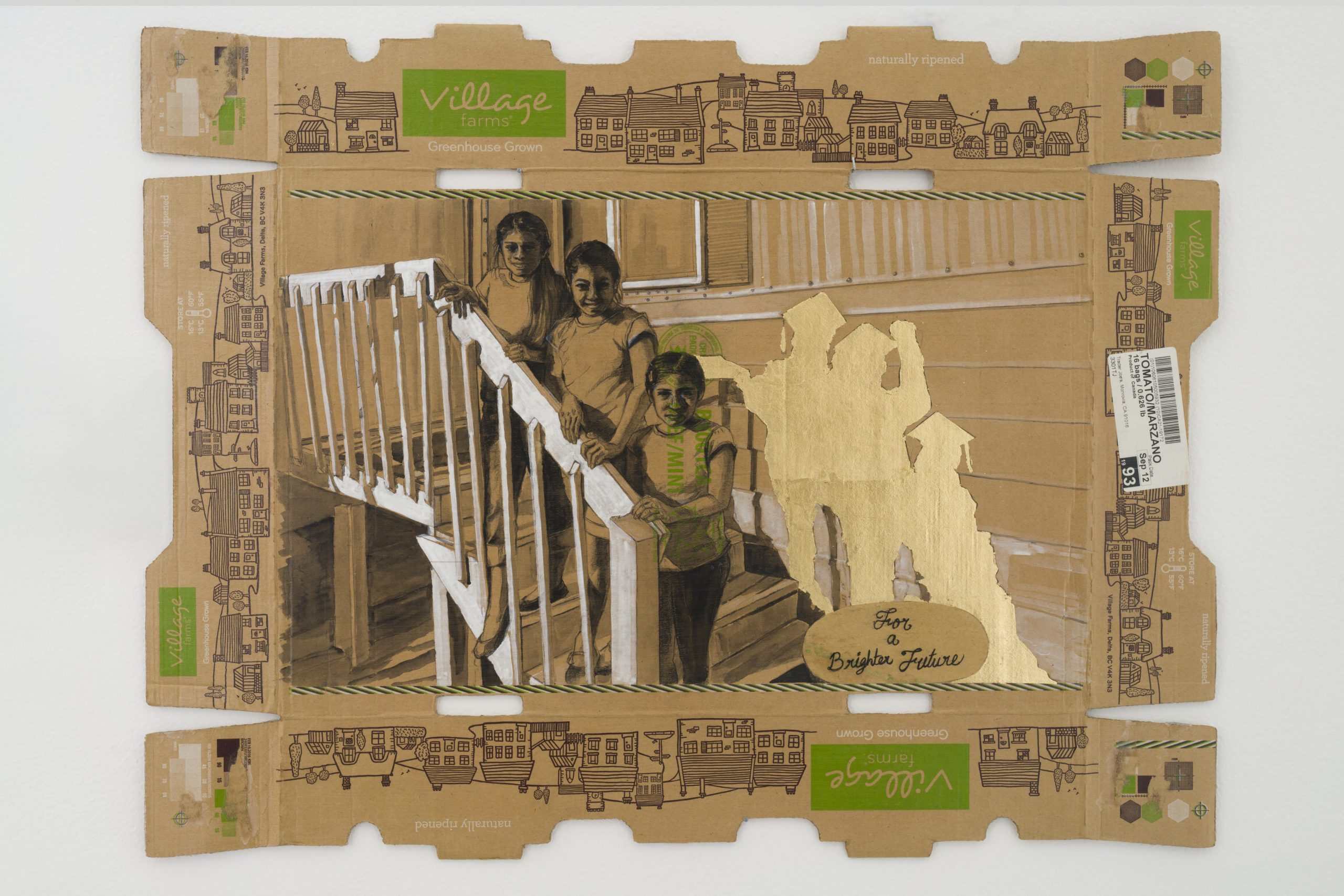

“[My work] is always informed by my experiences with capitalism. I started using gold leaf as a connection with the economy. When I started putting gold leaf in the background of the subject, it really made it look like a religious artwork. In churches, the saints always have some sort of gold leaf around their heads like a halo, so the idea is to elevate the farm workers. To me, farm workers are so important to this country’s economy, to its sustenance. They literally pick the food that sustains us. The gold leaf in the background elevates them and highlights their importance.”

Narsiso Martinez with LEGAL TENDER (2022) Ink, charcoal, gouache, simple leaf, and collage on produce cardboard boxes. 92.5 x 278 inches. Photo Credit: Yubo Dong / ofstudio. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

By leaving the representation of the wealthy to their corporate logos printed on cheery, disposable cartons, Martinez’s work, tender portraits of farm workers cloaked in varying degrees of sun and pesticide protection, reaches out from the political into the humane.

“I did a series of portraits of the farm workers without any kind of protection on their faces, no hoods, no bandanas. The idea was to show their features, to show their humanity and what they actually look like. And maybe just to create some kind of empathy so people can see them. People literally dress like that [to protect themselves from the] chemicals and the sun and the branches.”

Martinez described an encounter he had at his show at the Long Beach Museum of Art. His portraits lined the walls, images of masked workers who, with their hoodies and bandanas covering all but their eyes, bore resemblance to guerrilleros. “This lady entered and immediately said something like, ‘oh my god, why are you painting terrorists?’ I didn’t say anything, but I was hoping that she’d figure it out. As she walked around, she started seeing more context about the portraits, and I explained to her who they were and why I was doing the work like that. So I know that the context [of the cardboard boxes] is really important. [People] say that they’re grateful [to me] for [making] this kind of artwork, and that representation matters.”

USA Product (2021), Gouache, Charcoal, Collage, and Matte Medium on Cherry Box, 35 x 28.25 Inches. Yubo Dong / ofstudio. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

The word Martinez repeatedly uses to describe the lives of farm workers was “unfair.” It is unfair that farm workers have to eat on the ground, in the middle of the orchards, instead of at a proper table with chairs. It is unfair to have to work while sick, and to share one portable restroom for a whole field of workers. Martinez lived this struggle for years, on and off. Although, unlike most of the other workers who were working to feed their families, he was working to afford his education.

Throughout our conversation, Martinez continually returns to the importance of education as a pathway for migrant workers to achieve mobility in this country. He said that the more people know about farm workers’ working conditions and their value, the better chance we (the people) have of making a difference.

To a Brighter Future (2021)

Ink, gouache, charcoal, and gold leaf on produce. cardboard box 24 x 30.75 inches. Yubo Dong / ofstudio. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

“I went into the arts because I love to draw. I’m not an activist. It takes guts to be in the front lines marching and protesting, but I’m really shy. When I was [working] in the fields… it was sad that I couldn’t speak up for the farm workers, not even for myself,” he says. But there was a point at which he decided it had to be done. “I had to decide; I can do paintings and drawings for my own pleasure or I can talk about these issues in the fields. I opted for the second option because as someone who’s traveled to get a college degree and to have a voice, I can now bring some of those voices from the fields to different audiences. And in that way, maybe something can change. Or at the very least, people can be aware of these people that are in the fields. That they are humans, that they have needs, and that what they do is important.”

Martinez currently has three shows on view: Rethinking Essential, on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art in San Diego through June 4th, Los Huecos Del Agua, on view at the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago through August 27th, and Supreme Fresh, at Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle through July 1st.

Future exhibitions include the Armory show, September 8-10 in New York.

Gabriella Aguirre is a writer, filmmaker, ceramicist, and the Editor of LATINA.