Esmeralda Santiago sat at home on what felt like the first day of autumn in Northern Westchester, New York. Meanwhile, in Villa Palmeras, Santiago’s birthplace nestled within San Juan, Puerto Rico, I was perched at my desk, ready to delve into her life.

Santiago’s legacy is unprecedented. It wasn’t until her mid-30s that she penned her inaugural memoir “When I was Puerto Rican” (1993) after a Boston textbook editor, who chanced upon one of her personal essays, urged her to chronicle her childhood on the island and her experiences living in the United States. However, Santiago has always been an avid reader, and her connection to the written word dates back to her niñez in Macún, Toa Baja where she lived for ten years before relocating to New York with her mother and siblings.

Santiago grew up modestly and didn’t own many books, but her father frequently brought the newspaper home from work. Before she could read, he would share with her some of the sensationalist tabloid stories, a few of which she remembers as being “wholly inappropriate.” Once she was a teenager, Santiago discovered the prolific Spanish writer Corín Tellado through her many short novelas on Vanidades. Santiago’s school emphasized local literature, so she memorized and recited poems by local poets. “I always sought time to read, [reading] was a vacation for me, and I read everything I could get my hands on,” she shared.

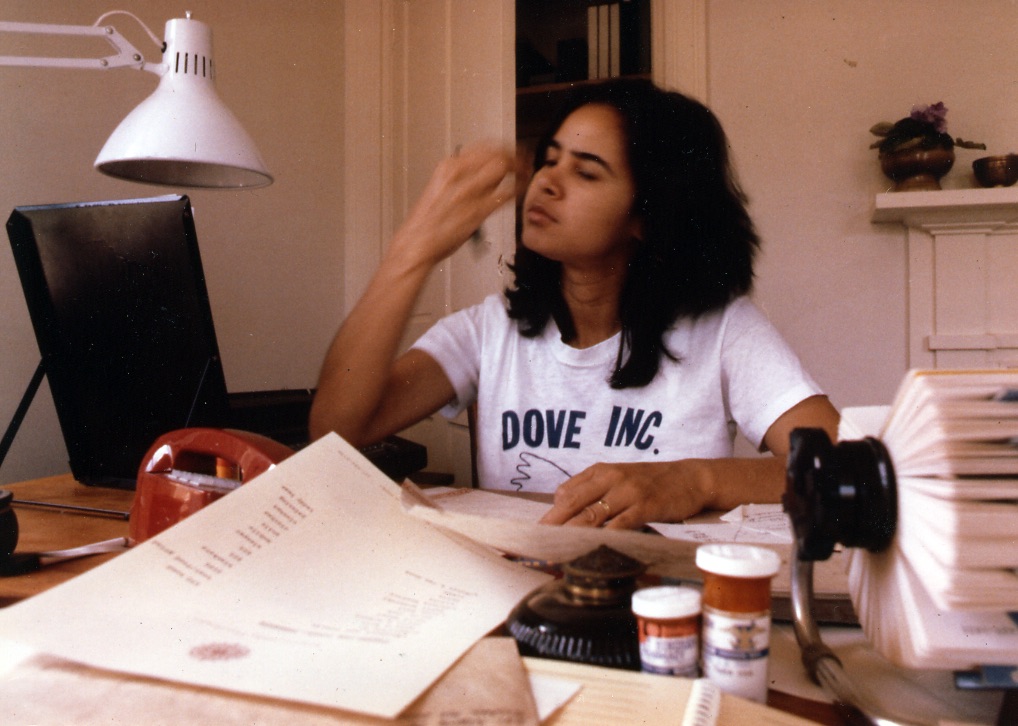

Esmeralda Santiago in Cambridge, MA by Sonya Sones (1975).

Though Santiago never dreamed of becoming a writer, her acclaimed work is now characterized by her fearless exploration of identity, the immigrant experience, and the complexities of family and love. She’s raw and honest. In her other autobiographies, “Almost a Woman” (1998) and “The Turkish Lover” (2005) she touches on the themes of self and belonging, especially as she navigates the challenges of adapting to a new culture and language. These themes, while they continue to shape her writing, ultimately gave her a new approach to life. “I had to stop focusing on belonging and become the person I wanted to be. I belong to myself,” she declared.

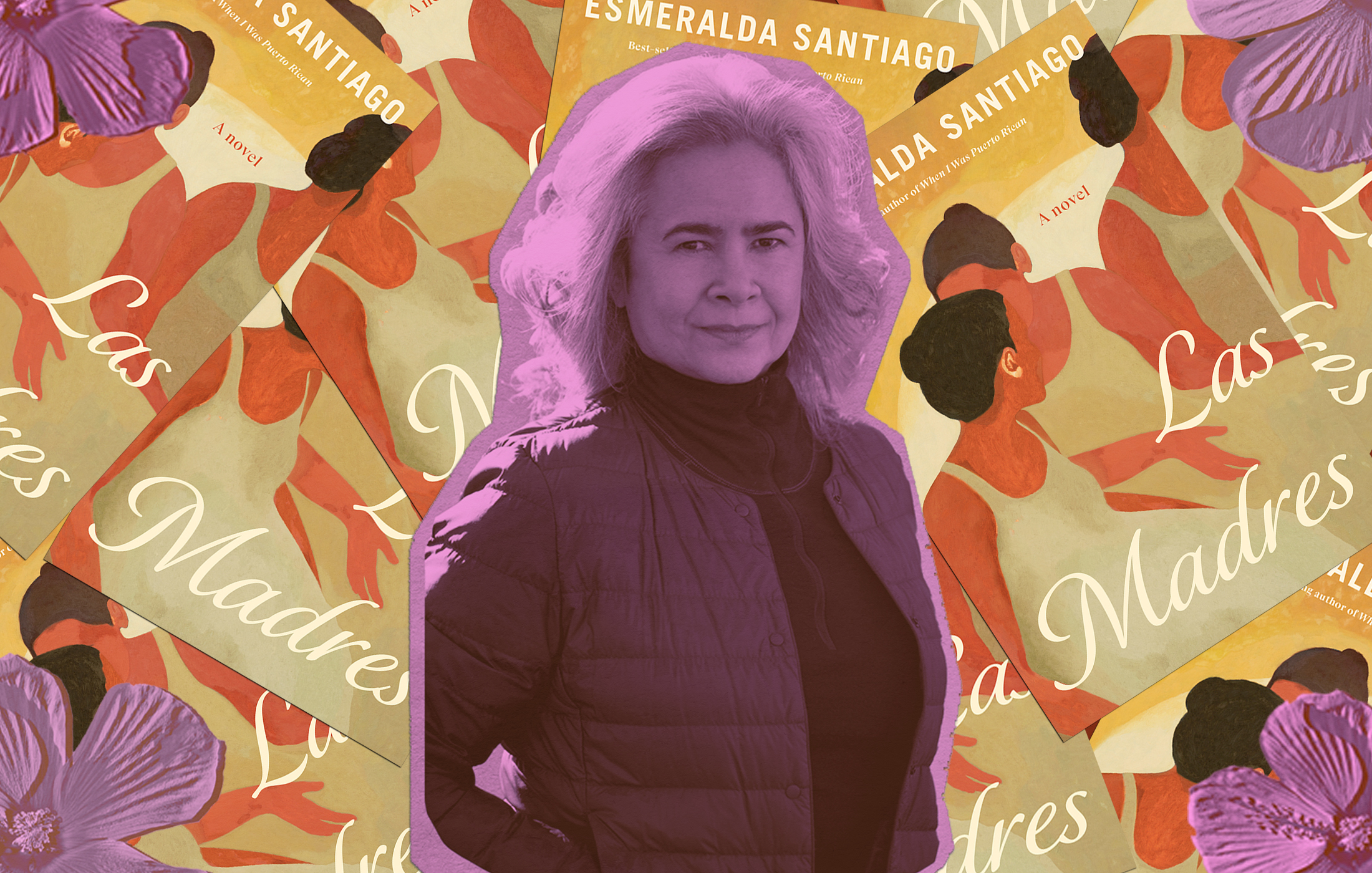

In her most recent novel, “Las Madres” (2023), Santiago explores a fresh perspective by highlighting the life stories of five Puerto Rican women residing in the U.S. These women, mothers and daughters, share a profound emotional bond with the archipelago. Santiago’s intimate familiarity with these types of stories, through her own friends and siblings, adds a depth and authenticity to their narratives.

Nevertheless, Santiago’s primary motivation for embarking on this work stemmed from the enduring impact of the devastating Hurricane Maria, in 2017, which coincided with her daughter’s birthday. Ever since, it elicits conflicting emotions. But the concept of addressing a hurricane had been brewing within Santiago long before the actual event occurred.

“I was talking to my dad, recording him before [he passed]. I asked him about Hurricane San Felipe II (1928), when he was nine-years-old. I said ‘Papi, do you have any memories?’ This ninety-year-old man became a terrified little boy before my eyes as he relived the hurricane, which he was evidently still processing at a late age,” Santiago commented.

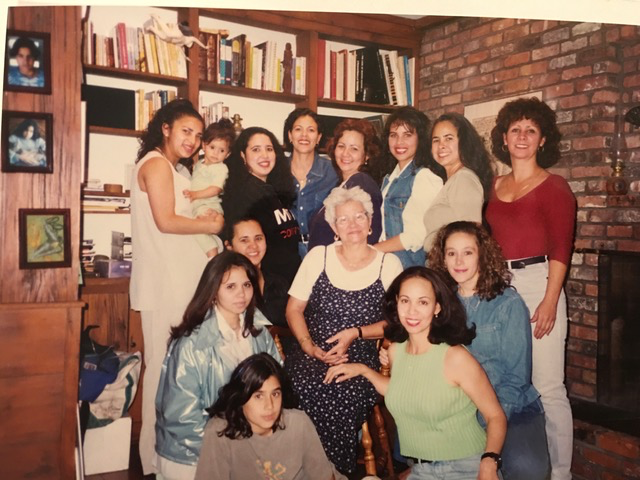

Esmeralda Santiago’s mother with her daughters, daughters-in-law, and granddaughters in 1998.

The theme of memory is threaded throughout “Las Madres.” Santiago suffered from a stroke in 2008 and became amnesiac for a few days, losing her ability to read and write. In her novel, she considered how to preserve the historical importance of events like Hurricane Maria within the context of identity. “What happens to someone who doesn’t have a memory?” she asks. “Our identity is tied to our environments, actions, and all our interactions, so if you forget everything, who are you?” Santiago continues.

This is the dilemma that the protagonist Luz faces in the book. Is she still Puerto Rican if she can’t remember where she’s from? Santiago has keenly observed the cultural dissonance that often confronts immigrants returning to their homeland, that sense of rejection by the very people who now perceive them as outsiders. “Of course [Luz] is still Puerto Rican,” Santiago answers her own question, adding that if Luz were in Russia or on the moon, she would still be Puerto Rican.

So how does Santiago wish to be remembered? She doesn’t think too much about it. She is focused on who she is right now. “All I care about is that my books continue to be read as long as the issues that I write about in them remain unresolved.” She reminds me at the end of our call that there is nothing special or unusual about her, and that she can only attribute her success to her hard work. “In Puerto Rico, we are constitutionally born to hard work and optimism.”

Francisco Gutierrez is a freelance artist and writer based in San Juan, Puerto Rico covering music and culture.