“For the First and Onlys: You have been assigned this mountain to show it can be moved.” Those are the opening words of “First Gen,” a new memoir by former White House Deputy Director of Hispanic Media Alejandra Campoverdi. The women’s health advocate and former congressional candidate has a longstanding career advocating for marginalized voices, and her now-bestselling book is a continuation of every mountain she’s moved so far.

From developing Latino-focused communication strategies for the White House to producing a PBS documentary about hereditary cancer based on her experiences as a high-risk cancer carrier, Campoverdi has been at the forefront of shedding light on undercovered stories. Most recently, she has launched a fellowship to support first generation students with financial need, a topic she cares about as a first-generation college graduate herself.

Latina sat down with Campoverdi to chat about her book, “First Gen,” which delves into her experiences growing up in a low-income immigrant household in L.A., and her journey to becoming a White House aide to President Obama. The memoir focuses on the “Trailblazer Toll,” a set of challenges that those who are the “First and Onlys” in their families, looking to reach specific milestones, face as they pave the way to success. Through intimate anecdotes, including the troubled love lives of the women in her family and her Maxim photoshoot scandal while working at the White House, Campoverdi gives a refreshing take on the American Dream, one that is far from being a glossy magazine cover story.

Campoverdi as a child with her family. Courtesy of Campoverdi.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

At the beginning of the book, you mention the “Trailblazer Toll” which includes concepts like “Invisible Inheritances,” “Bicultural Balancing Act,” “Breakaway Guilt,” among others. I think many “First and Onlys” can relate to one or more of these terms. Could you talk more about your decision to focus on them as pillars for your book?

It was very intentional. I always say you can’t heal from that which you can’t name. And a lot of these different pieces and nuances in the first-gen experience don’t get talked about as much as imposter syndrome. So throughout the book, I introduce “trailblazer tolls” in each chapter and the stories are in service to illustrate those “tolls.” I don’t think that they’re necessarily comprehensive but in my conversations with young people and in my own experience, these are the most widespread and common.

“Breakaway Guilt” is one that uniquely follows you because the higher you go, the more extreme that guilt experience is. I took my aunt to lunch last week and she said, ‘I just realized I’m never going to be able to not work. I’m never going to be able to retire.’ And she’s on social security but it’s not enough. We’re sitting at this beautiful cafe in this beautiful city and I could feel the breakaway guilt. I was trying to solve it in my mind already. Like, what can I do?

Your family ties and your background are center points in the book. How was the process of learning about your family history? Did you struggle, did it hurt, was it healing?

All of those things. Sometimes people don’t ask questions, and some boxes… people keep the cover on them pretty tight. A big help for me was my grandmother’s brother. He was there as a nine-year-old, I believe, when my grandparents met. I had heard the lore in our family of how my grandparents met, but he was there so I had someone who had witnessed a lot of it in real time.

Like I said at the beginning of the book, a memoir is a work of memory. It’s not a historical document, so you do the best you can. One of the fascinating parts of this experience was that I found things out that my mom and her sisters didn’t know. I was sharing with them the dynamics between my great grandparents and their relationship and connecting dots. It was a really beautiful experience of understanding our history in a new way.

Courtesy of Campoverdi.

I love that you encourage readers to do the same by providing an empty genogram [a graphic representation of a family tree that displays detailed data on relationships among individuals] at the end of your book. How did that come to be?

I learned about [genograms] in grad school. To me, our genetic history felt like one piece of the equation. You don’t have to be an expert to know that there are patterns in families that seem to repeat. How do we zoom out and take a look at what that is? That’s what a genogram is, a family tree of your emotional inheritances through generations. We might feel like we know these things but it’s different when you start writing them down and connecting literal dots. It was even eye-opening for my family members [who had] lived through it.

I wrote “First Gen” with one intention, and that was for people to come away from it feeling seen, feeling their experiences validated, and feeling less alone. This was my journey, and one of the reasons why I include these resources is because those were things I actually did.

In multiple instances, you talk about “acting white” and battling with your idea of what Latino pride is. Could you talk about the process of coming to terms with your identity in a healthy way?

I think a shift happened for me around my identity when I understood my unique position in a different way. I used to feel like I had to be a bridge between two different cultures, between two different social classes, and between two different identities and experiences. And for some people, it’s three or four. We stand at the intersection of so many different experiences. I started to realize that I wasn’t responsible for bridging all of this, I was the bridge by existing, that was enough. That helped pull off [some] weight from my shoulders, the feeling [of responsibility] to get it right.

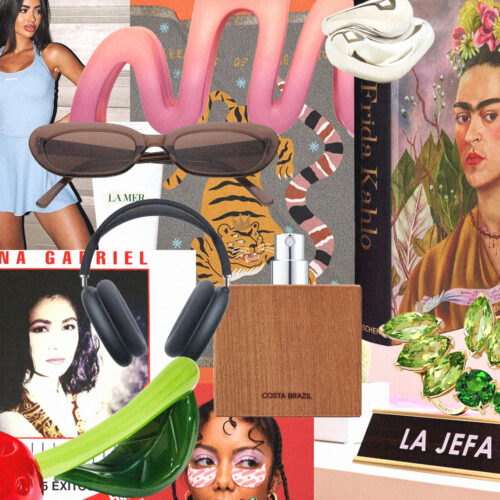

Courtesy of Campoverdi.

Each chapter is named after a song. Tell us more about how you selected each song, and why each is important to you.

Music is a big part of my life, and when I look back at certain times in my life, and I know I’m not alone in this, a song takes me back there. It’s one of the reasons why I love music. When I was writing the book, there were a lot of ways that I tried to evoke memories in my body and myself. And the way that I did that was, I would light a veladora de la Virgen right next to the computer to keep me company, I had photos of my ancestors around me but the music was such a big part of it as well. When it came time to name the chapters, it just felt so organic to name them after the songs, which were the stories of those times. Incidentally it resulted in a playlist.

Why did you want to publish a memoir now? What made it the right moment in your life for you to work on this project?

I had to grow into this book; I couldn’t have written it five years ago. I hadn’t lived it yet, and I hadn’t reflected on what that meant. It’s an interesting question because when you think of someone writing a memoir it’s usually at the end of their life. But the reason why this made sense now is because [while] it is a memoir, it’s more than that. [This book] illustrates this broad emotional arc of the “first-gen” experience that has, in a lot of ways, run its initial conclusion for me.

At a certain point, you get to that place and you say, ‘okay, I went to school,’ or ‘I got this job,’ or ‘I have this relationship.’ And then you have that inflection point where you get to decide what the rest of your life is going to be like. And that’s where I got to be. It’s a beautiful place,one that is hard-won and worth reflecting on after you get there.