Everything in Tulum — a trendy, laid-back oasis in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula — is designed to make you feel good. Not good in the glitzy, over-indulgent style of St. Tropez, Miami, or Ibiza, those infamous playgrounds for the moneyed classes. Rather, Tulum promises an atmosphere that will elevate your consciousness and make your tan glow as you manifest your ideal self.

As consumers, millennials with expendable income are often in pursuit of ethical alternatives to traditional choices. As the climate crisis escalates and awareness of the human costs of global consumerism grows, this consumer class endeavors to be eco (-friendly, -aesthetic, -conscious) in its consumption. Tulum has come into fashion as a chic alternative in a world of harmful mass tourism, attracting both long-practicing New Age acolytes as well as influencers and young professionals. Investment bankers and spiritual guides alike seek paradise there, hoping to dabble in clean, luxury living and ethical merry-making.

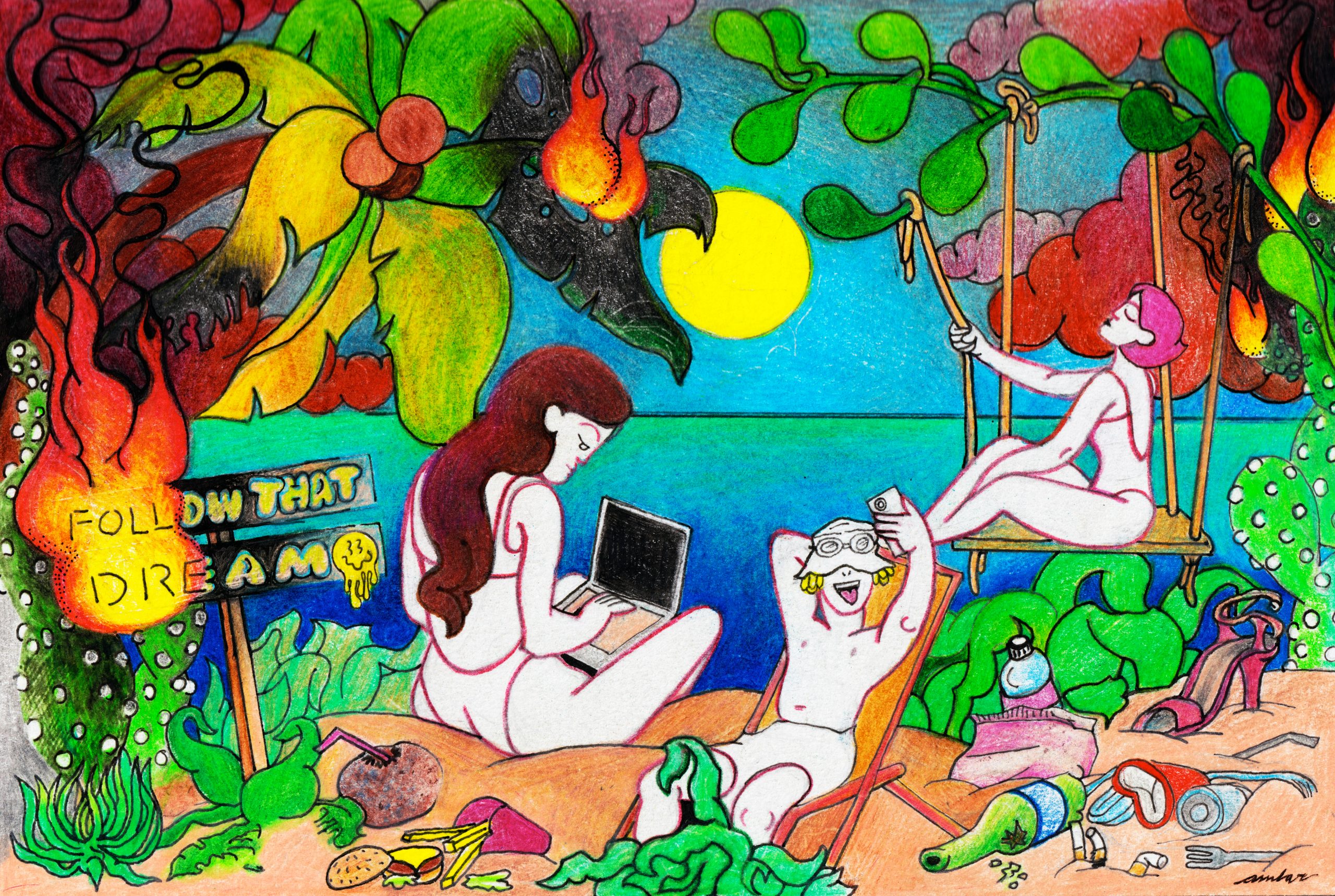

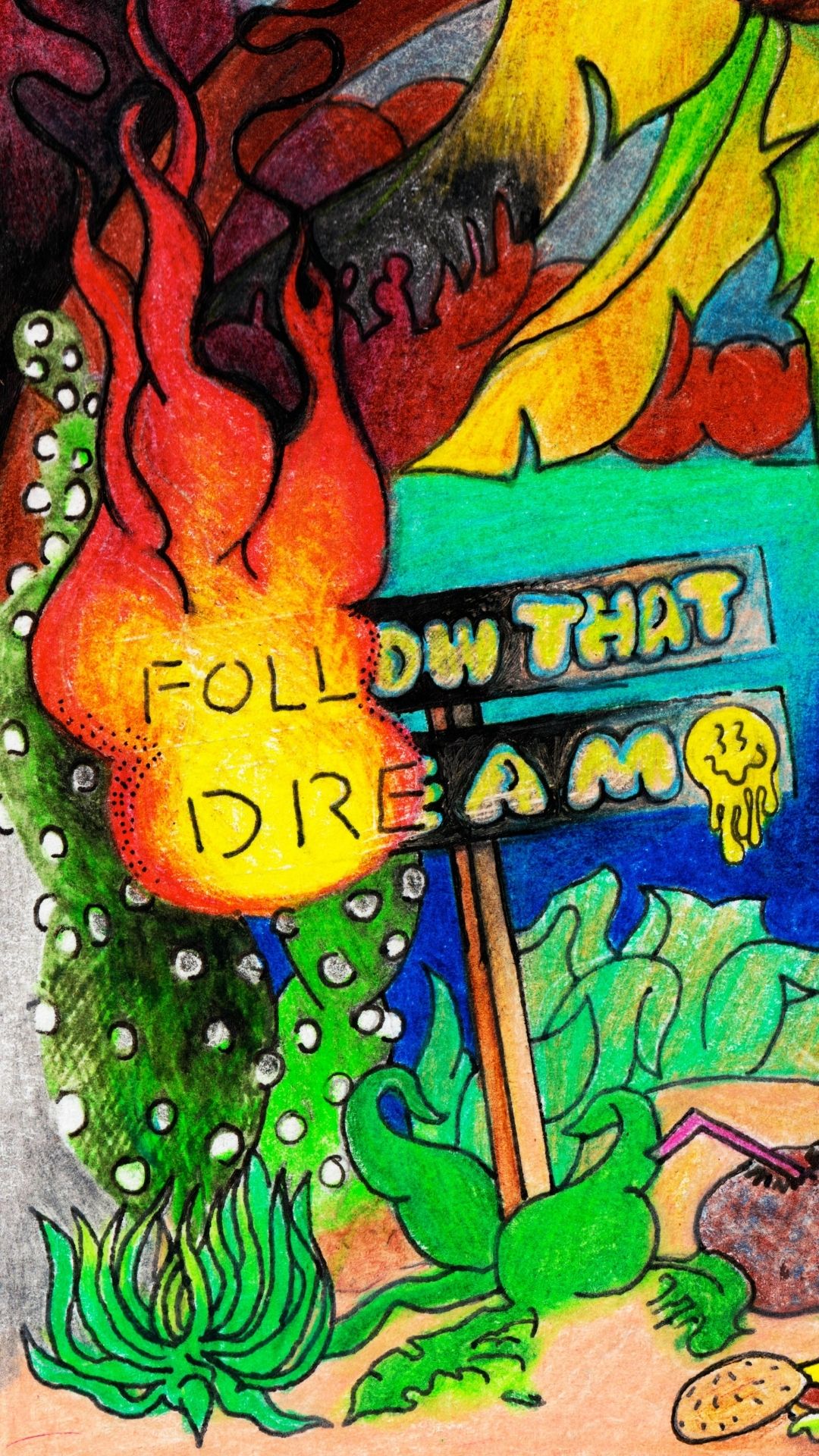

The version of Tulum seen by tourists and on Instagram is molded in the image of “eco-chic,” an umbrella term defined by an amorphous combination of lifestyle, ecology, politics, spirituality, beauty standards, and virtue — anything we can buy, sell, or do that promises absolution from our ecological sins. But “eco-chic” isn’t merely the marketing of moral postures to consumers. It traffics in the aestheticization of everyday life. According to Chris Hudson in the anthology “Green Consumption,” green is more than just good — it’s a sensory delight. An eco-chic Instagram photo is beautiful because it holds a promise that the serenity represented on screen can be translated to material life.

The implicit appeal of landscapes off the beaten path helps explain the rising popularity of ecotourism hotspots like Tulum. Like any other product marketed on a feed, the natural world is used in service of moral and aesthetic gratification. The common thread is consumption; eco-chic is above all an “economic regime” of things or places, Hudson writes. Thus it is not only the objects of consumption in Tulum that travelers covet, but also Tulum itself, as both a signifier of virtue and luxury and as a visual product for social media. But this product requires construction and maintenance, along with labor, land, and capital.

Hungry for Meaning

If you visited Tulum in the 1990s, you would find a small town with a population of about 2,000, a few beachfront homes and only one or two hotels, all of which lacked consistent electricity and running water. There would be ample space for sleeping on the beach, of which adventurous backpackers would take advantage, stringing up hammocks or roughing it in the sand.

Today, security guards patrol the white-sand beaches in front of boutique hotels to keep out trespassers. Travelers to Tulum will not hear the rustle of haphazardly-pitched tents or the creak of hammocks. Instead, they will see a marvel of design and photogenicism; Tulum’s wellness centers and beachfront yoga studios are straight out of an Instagram feed — drop in a bronzed, wind-blown model and you would have an ad for the luxury brand of your choosing. The earth tones, rattan chairs, and pale pink accents of the restaurants and bars inspire whimsy and delight; beach clubs are both rustic and manicured, a triumph of eco-modernist aesthetics.

Tulum is a triumph of digital culture. Its rise as a site of visual pleasure, one that can be photographed and disseminated, parallels a cultural shift towards non-material goods as markers of elite status. Consider Matcha Mama, a plant-based juice bar and one of the “more Instagrammed places in Tulum,” as American co-founder Ryan Rafferty says. He and his partner, Mexican Alexis Madero, founded the business in 2017.

Madero is proud of the work they’ve done to make the space beautiful. Its white interiors, beach swings, and pink-flamingo wall decals can be seen all over Instagram. The design matches, or rather signifies, Matcha Mama’s appeal, which Madero says is “really what people are looking for these days. People want to be healthy and have a healthy mindset.”

It comes as no surprise that the eco-chic movement, along with its call to return to the moral simplicity of a former time, has become popular among the traveling class. Ryan says that he founded Matcha Mama on the principle of “the simple life,” but during the pandemic the desire to “feel good” heightened.

Is it the chlorophyll water that customers love consuming, or the idea of a healthy lifestyle? As sociologist John Urry argues, the late 20th century offered forms of specialized consumption like tourism, where, “use value was usurped by symbolic value, and the consumption of signs rather than material goods became key features of the global economy.” In “an economy of signs and space,” a trip to an Instagram-worthy vista becomes just as attractive to the consumer as the purchase of traditional luxury goods.

“The Pleasurable Periphery”

Tulum is a product of the late-stage tourist economy. Across the globe, humans have re-organized entire regions, labor patterns, and supply chains around tourism. In the past century, tourism has gone from a rarefied privilege to an integral part of contemporary social life despite being prohibitively expensive for most individuals. Tourism is a sign of upward social mobility, class distinction, and leisure. But the right to tourism — and the perception that we are entitled to it — is widely accepted in the West.

Tourism became a consolidated industry after the Second World War. As consumer power grew in tandem with the emerging middle class, mass tourism rose in popularity for those with expendable capital in wealthy nations. Beginning in the 1980s, international organizations like the UN World Tourism Organization began to articulate tourism as a crucial component of human fulfillment. Since then, tourism has become the fourth-largest export sector in the world.

The Yucatan Peninsula’s international tourism trade originated not in Tulum, but about 80 miles northeast in Cancun. In the 1970s, Mexican bankers identified Cancun as ripe for development. The bankers saw in Cancun the ideal “sea, sun, and sand” destination and a convenient alternative for hosting US tourists to Cuba, which had closed its borders to Americans. The official committee in charge of selecting resort sites had two criteria. The first was that the location be visually pleasing, with an appropriate ecology for leisure activities and the second was that the site be located in “underdeveloped” zones. Once the committee approved the “Cancun Master Plan,” the city was built up almost from scratch, using primarily Maya labor from surrounding areas. The region became Mexico’s first mass tourism destination. Historian Fernando Marti writes of the plan: “[A] group of bankers conceived an absurd project: found a tourism city in dense jungle with the basic idea of capturing foreign exchange.”

Concurrently, across the Caribbean, post-colonial countries like Jamaica and the Bahamas were pursuing modernization and economic sovereignty through one of the few avenues available to them in the age of neoliberalism: mass tourism and resort economies. Resort tourism, conceived as the “industry without chimneys” became a national development strategy. It hinged on creating the perfect balance of authentic “Third World” exoticism and modern, familiar comforts — a “pleasurable periphery,” as tourism historian Louis Turner coins it.

Yet the pleasurable periphery is as unstable as it is manufactured, subject to the whims and tastes of the globe-trotting leisure class. In the 1990s, as the environmentalist movement gained traction, scholars and tourists alike began to criticize mass tourism for its hyper-commodification of local ecologies and communities, according to Matilde Córdoba Azcárate’s ethnography “Stuck with Tourism.” When activists suggested “ethnic” and ecologically oriented tourism as a solution, private and public actors jumped at the chance to cater to the newly conscientious spending classes. Enter the “conscious” traveler who aims to find the most unadulterated pockets of nature — scenic reassurances that parts of the world still exist in uncorrupted form in the post-industrial age.

By the early 2000s, the global elite shunned mass tourism and places like Cancun. Suddenly, surrounded by sky-rise condos that blocked views of beachy paradises and shantytowns that prompted shame and discomfort, the conscious traveler understood the perils of consumer capitalism. She sought a subtler, less egregious form of luxury. She wanted a traveling experience that confirmed her conception of herself as laid-back and low-maintenance. So the “pleasurable periphery” shifted once again, seeking ever-more virgin land to develop. Investors and entrepreneurs set their eyes on Tulum, which they could market as the more authentic alternative for those dissatisfied with cities like Cancun.

Tulum, as the perceived undiscovered world apart, was not already there, waiting for visitors. It had to be imagined and constructed in the image of the adventurer’s desires. Its construction did, however, displace the long-standing Maya communities that were already there. The disruption forced Mayas to abandon agricultural production and adopt wage labor as a matter of economic survival. Tulum’s “ejido” system, in which land tenure is communally held and village-based, facilitated the waves of gentrification and dispossession.

The “ejido” system dates back to the post-revolutionary Mexican government, which aimed to redress landlessness among peasants through a policy of land redistribution. Ejidos were government land grants given to communities who would then collectively maintain the land, without owning it. This land distribution process also entailed promoting non-indigenous settlement on indigenous lands. In the 1970s, the government provided peasants from states like Michoacán and Tabasco with grants to land deemed “uncolonized” in the states of Quintana Roo, where Tulum resides. In Tulum, Mayas, who before the “ejido” had de facto ownership and control of the territory, suddenly found that the state now owned and regulated access to the land, and could give “ejido” titles to Mexican and Yucatec developers who sought to take advantage of the program.

Despite post-revolutionary efforts to curb land encroachment, the “ejido” system yielded mixed results. In 1994, land redistribution programs virtually ended with the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). NAFTA paved the way for the privatization of “ejido” lands by making it permissible for “ejidatarios,” members of the ejido, to sell, rent, sharecrop or mortgage land parcels to foreign capital. “Ejidatarios” could now sell parcels of land to developers. For some “ejidatarios,” in the Yucatan, many of whom are Mayas, selling their land was a lucrative economic opportunity, albeit a singular one. With agricultural production waning across the region, there were few other options to make a living. Many “ejidatarios” thus sold their land off to developers. As a result, developers in Tulum only had small squares of land to develop, and could not build the mega-resorts seen in other parts of the Riviera Maya. The solution was to build small, exclusive “eco-hotels” that now house the legions of wealthy travelers who come to visit.

Mental Gymnastics

Tulum’s infrastructure is only designed to sustain around 7,000 people. Now the town, which had only 3,000 inhabitants in 1995, hosts more than two million tourists per year and has a local population of 35,000. Tulum’s coastal area lacks proper access to the power grid, and hotels rely largely on diesel generators to power their air conditioners and other appliances. The city also lacks waste management and drainage infrastructure, and for years dumped its garbage in open-air landfills in the jungle. As it decomposes, the trash leaches into the region’s fragile underground water system and eventually the drinking water.

This has not stopped travel to the region. Although Tulum’s pollution has worsened, it remains somewhat hidden behind the image of paradise manufactured for our enjoyment. According to the Washington Post, the number of American tourists visiting the state of Quintana Roo in 2021, where Tulum and Cancun are located, has increased by 23 percent compared with 2019.

Some of these travelers have even decided to stay, extending their week-long vacations into full-time residency. Tulum has recently become a hot-spot for the “digital nomad,” individuals who work remotely so they can travel the world, promising a relatively affordable escape from the demands of a former life. While the rest of the world shuttered, more and more digital nomads flocked to Tulum, forging ahead with their individual paths to self-discovery. Groups on Facebook, like “Digital Nomads in Tulum,” have grown to nearly 4,000 members in the past year.

Nazieh Fazil is one of many who traveled to Tulum during the pandemic. She is the founder of CoWorking Tulum, a “premium CoWorking community and experience,” that she started last year with her brother. Fazil lived in one of the most expensive parts of Manhattan, so close to her office that she could walk to work. Then her company went remote. “It didn’t make sense for me to be paying rent when the U.S. was completely shut down.” As Fazil pointed out, economic incentive is one reason why Tulum is so attractive to remote workers: the rent is cheaper than cities like New York, London, or L.A.

The locals and expat community, she says, are very conscientious, and know that they are guests on the land. They are “actively working to try and mitigate as many risks as possible.” She tries to see the spaces for hope which tourism offers. “Part of the positive includes the impact on the economy, the impact on the local people, the impact on jobs, and Tulum becoming an innovation hub, because of the minds that are coming in and converging here.” Among these innovative minds, she lists, “social media people, Bitcoin miners, and neuro-hackers.” Yet it seems unlikely that such a milieu could continue to grow its ranks without displacing existing ways of life, further entrapping locals and working-class populations in an economy where the only choice is to serve in the tourism industry.

Recently, certain environmental harbingers have made reality harder to obscure. In the past few years, the invasive algae sargassum has barraged Tulum’s beaches, turning the clear water into red muck. Neither the vista nor the contracted laborers who are hired to shovel it away by hand make for a photogenic view. The private sector has worked tirelessly and invested large sums to remove sargasso daily from the beaches in front of their hotels.The public beaches in Tulum, where locals go, receive no such cleaning.

The cleanup effort is concerned mainly with appearance. Many hotels lack an adequate disposal site, and once they clear the sargasso off their beachfront, they do not dispose of it properly, leaving it to rot in parking lots or piles on the beach. Decomposing sargasso is a serious source of contamination. Once the macro algae have decomposed, they release gases and liquids that end up draining into bodies of water. For the hotel owners, there is little else to do but continue with the Sisyphean feat. Their patrons were promised white-sand beaches, not invasive algae.

Excessive Growth

Tourism’s promises attract equally those who want to raze jungles to build mega-resorts and those who want to protect those environments. And it is an intoxicating promise of improvement. Countries locked out of other economic production can, at least, produce these spaces, both in the imagination and in concrete form. But the meticulous expansion of these curated “wilds” — and indeed, Tulum’s entire economy — depends on the continued exploitation of a Mexican labor force.

Tulum’s tourism industry relies on migrant laborers residing in Cancun, that densely populated metropolis now considered tacky by the elite traveler, as well as on local Maya communities. Dr. Bianet Castellanos, an anthropologist and a faculty member at the University of Minnesota, has spent over twenty years studying Maya migration and the tourist trade in Cancun. She commented that Tulum’s boutique hotels and beachfront clubs source the majority of their labor this way, noting that “to have the labor necessary to run these places, you need to have a high concentration of people — cheap, expendable labor.”

This is the Tulum that visitors don’t see — or rather, try hard to ignore. Is handing out paper straws and becoming a zero-waste enterprise like Matcha Mama enough in the face of such structural inequity? Peripheral communities absorb the unsavory elements of this predatory labor relationship, allowing Tulum to appear both ethically and aesthetically pristine. This obscures the fact that paradise implicates even the well-meaning developer with the social and economic forces that surround them, revealing their position upon eco-capitalism’s scales of power.

While many “eco” property owners and businesses want to play a role in making Tulum sustainable, they often feel victimized by the growth from which they profit. One way eco-chic businesses handle the dissonance is by an act of differentiation. There are people like themselves, who are invested in the community, and then there are the “bad consumers” who just want to party and take pictures, along with the broods of developers who enable them.

Manuel Saracho is a Mexican citizen who is the sales director of Xel-ha, an archeological site and a key port for the Maya in the first century and. It is now a crowded theme park and ecotourism development near Tulum. Yet even Saracho, whose career depends on mass tourism, regrets Tulum’s non-exclusivity. “We don’t want those Daytona Beach Spring Breakers. But unfortunately, that’s what Tulum has become.”

Alexis Madero, Matcha Mama’s co-founder, thinks Tulum is no more exploited or exploitable than locations across the globe that undergo development booms. “All over the world, there are these beautiful, perfect paradises. And, now these secret places, like Tulum, are exposed because of social media.” Madero is now leaving the town she helped brand. She, along with her partner Rafferty and their three-year-old are moving to a gated community thirty minutes away from Tulum.

Other business owners place the blame squarely on the Mexican government. Saracho thinks that tourism’s effect on the town’s local population is “deplorable, everything that’s happening with assaults, and drug addiction. The government’s role has not caught up with the amount of investment here.” Saracho’s girlfriend, Irene, hails from Cuernavaca and owns an Airbnb in Aldea Zama, Tulum’s biggest real estate development. Aldea Zama’s sustainable ethos compelled Irene, who wanted a place to pass on to her kids, to invest.

“Unfortunately, the government is more focused on seeing how much it can rob and generate in profits,” she says of her frustrations with Tulum’s governance. Yet Aldea Zama is not immune to the flawed systems that fuel excessive growth. Aldea Zama’s website states that the development mixes the “antiquity and the mysticism of Tulum with a contemporary lifestyle.” But it is owned by MayaZama, a Mexican real estate company whose partners have been linked to cases of property fraud and corruption across the peninsula. Despite the invocation of theMaya people in the name, the partners of this company tend to be upper-class Mexicans who have leveraged their capital to buy “ejidos” or businesses.

It’s no wonder that the current conception of paradise is a place that can fortify an individual’s moral selfhood, where, ideally, she would be able to go about one’s wellness routines and career without experiencing pangs of guilt, or dread, or fear. Tulum’s developments and hotel zone have been designed to be enclosures of luxury, visually and spatially separate from the shantytowns that have cropped up along highways and in the outskirts of town. In eco-paradise, the traveler lives apart from the system she upholds — away from the “bad” consumers and the greedy developers of places like Cancun — and can believe she is outside of it.

But where will the “good consumer” go once the predatory logics of tourism in Tulum become too visible and too unpleasant to bear? Perhaps, as many Tulum lovers say, the virtuous will stay put, working to improve ecological conditions and empower local communities. Or perhaps they will set their sights on other idyllic landscapes. On undeveloped pockets of the world where it is easier to be good. Where escaping the ambivalent moral regimes of late capitalism is just a matter of getting on a plane and going.

##

Special thanks to Dr. M. Bianet Castellanos, Dr. Ana M. Juárez, and Dr. Matilde Córdoba Ázcarate.