In 2017, a video began to spread across Twitter and Facebook, capturing an “impromptu neighborhood dance party” that began when neighboring Punjabi and Mexican families in suburban Stockton, California, combined their respective house parties in the street. Clips of the party captured on cell phone were edited to show how partygoers took turns dancing to each other’s music in the suburban street of Stockton, California. “THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS WHEN TWO CULTURES MEET” BuzzFeed News proclaimed, emphasizing that the virality of the content was to be found in the ostensibly novel fusion of South Asian and Latino music and dance.

But the blending of the ‘traditional’ styles of Punjabi and Mexican dance in Buzzfeed’s 2017 report was no outlier. In fact, a couple years earlier, just a few miles east in San Francisco, the Duniya Dance and Drum Company and Ensembles Ballet Folklorico de San Francisco collaborated to develop choreography that brought together Bhangra, a folk-dance originating from Punjab region of India and Pakistan, with the Mexican regional styles of Ballet Folklorico. The performance, entitled “Half and Halves,” was organized to commemorate the community of Punjabi-Mexican families that emerged from the conditions faced by immigrant populations in early 20th century California, including immigration restrictions, racial segregation, and anti-miscegenation laws.

The U.S. Southwest is dotted with Punjabi-Mexican enclaves in states like California, Texas, and Arizona. One such enclave is Yuba City, California. The Punjabi-Mexicans of this locale trace their origins to a population of Punjabi migrant men who settled as agricultural laborers in California during the first decades of the 1900s, before the Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917 restricted nearly all immigration from Asia. These men were largely restricted from entering the United States with wives or other family members because of anti-Asian immigration policy, which sought to prevent the entry of nonwhite immigrant populations into the U.S. except as a source of cheap, and disposable labor.

“Half and Halves”

The first recorded marriages between Punjabi men and Mexican women occurred in 1916. Punjabi men sought local women whom they could legally marry, for both companionship and as a source of domestic labor. As Karen Leonard, a professor of anthropology at the University of California at Irvine explained in her book Making Ethnic Choices: California’s Punjabi Mexican Americans, “Many Punjabi’s married the Mexican women that worked on their land because of their cultural similarities and proximity. And when they’d show up at the county record office, they could both check ‘brown.’ No one knew the difference.”

In the early 20th century, Mexican women often lived and worked in close proximity to male Punjabi immigrants, increasing the likelihood of marriages between the two groups. Moreover, driven north by the political and economic tumult of the Mexican Revolution, an even greater number of Mexican families began to settle in the agricultural regions of Southern California throughout the 1910s. Thus, it was no coincidence that many Mexican families picked cotton alongside Punjabis.

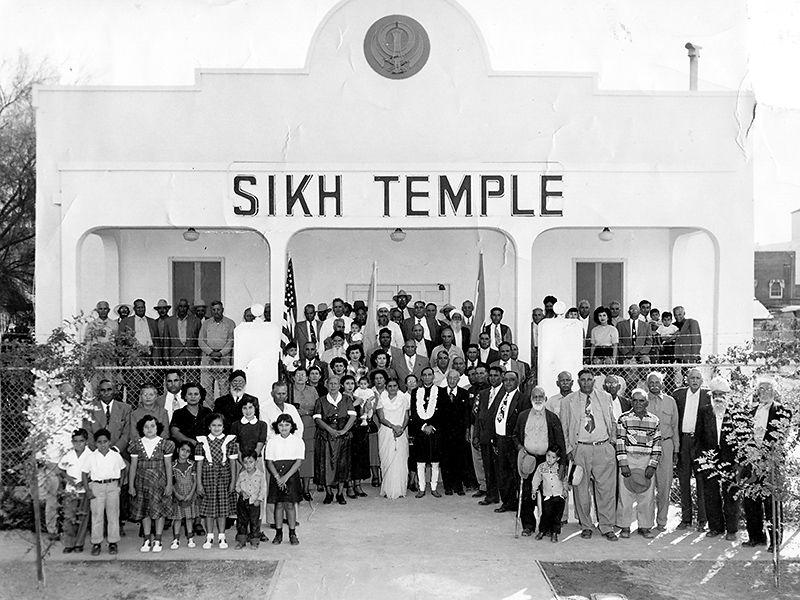

The El Centro, Calif. Sikh Temple, photographed in 1951. Source: https://earthjustice.org/blog/2021-may/how-asian-american-farmers-shaped-our-cultural-food-landscape

At the time, farm labor in the Southwest was often segregated based upon a perceived racial hierarchy that placed so-called “Hindu” and Mexican populations in the same low position within the state’s agricultural labor pool. Mexican women’s work in cotton fields also mirrored the gendered divisions of labor found in rural Punjabi life, as the work of picking cotton was one of the few forms of agricultural labor that Jat Sikh women performed in Central Punjab.

Marriage between Punjabi men and Mexican women did not occur without controversy. Local papers recorded several instances of Mexican men retaliating against both parties for the supposed ‘theft’ of ‘their’ women. In one instance, a group of Mexican men abducted two Mexican sisters who had married Punjabi men in the Imperial Valley and forced the women across the border into Mexico, where they were imprisoned for several days and flogged by their captors.

Dinner at the Phoenix home of Rosa and Jiwan Singh in 1951. At center is their guest, Indian professional wrestler Tiger Joginder Singh. Source: https://www.saada.org/project/timeline/punjabi-mexican-families

Despite early resistance to these cross-cultural marriages, a network of Punjabi-Mexican families began to develop across the U.S. Southwest, stretching from El Paso, Texas, through New Mexico and Arizona, and stretching as far north as Fresno and Yuba City, California. Punjabi customs prompted men to marry sets of cousins, close friends, or even sisters. Thus the mixed-race community that developed remained remarkably tight-knit.

In some cases, Mexican women would connect Punjabi bachelors with relatives still living in Mexico, and some Punjabi men traveled across several states to find their partners — occasionally returning home with not only their new brides, but also their sisters, widowed mothers, or other female relatives who sought husbands of their own. Futhermore, a significant center for Punjabi-Mexican life emerged in Imperial Valley, located along California’s Southern border, where over half of all Punjabi-Mexican households settled.

Most children born of Punjabi-Mexican marriages were raised Catholic and spoke Spanish in their homes, but household cooking typically drew from both Mexican and Punjabi cuisine. The Punjabi-Mexican generation became known locally as “half and halves” and many members recall facing prejudice from both Anglo and Mexican schoolmates.

Ernestina and Bishan Singh’s family, photographed in 1932. Source: https://earthjustice.org/blog/2021-may/how-asian-american-farmers-shaped-our-cultural-food-landscape

Bound Through Dance

The collaboration between the Duniya Dance and Drum Company and Ensembles Ballet Folklorico de San Francisco featured several numbers that addressed different facets of life in the Punjabi-Mexican community including farm life, marriages, and racial discrimination, and clips of interviews with the Punjabi-Mexican community members who inspired the show were featured throughout the live performance.

In Yuba City, the Punjabi-Mexican community organized their own dance to celebrate the legacy of the region’s unique “bicultural” settler community. The first annual Punjabi-Mexican dance known as “Old-Timers’ Reunion Christmas Dance,” was held in 1974 in response to the shifting demographics of California’s South Asian communities following the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This liberalization of U.S. immigration law allowed increasing numbers of newly-arrived South Asian immigrants to settle in the U.S. The Old Timer’s Reunion Christmas Dance featured mariachi bands and included Mexican-American friends and family, in sharp contrast to the annual Sikh Parade that newcomers began organizing a few years later.

“Punjabi-Mexican Wedding”. Source: https://www.saada.org/item/20150317-4088

The Old Timer’s Dance, as it came to be called, eventually expanded to include the classmates and neighbors of the event’s founders, so by the late 1980s only two of the organizers and about ten percent of the attendees were descendants of Yuba City’s Punjabi-Mexican families. And by 2008, the Old Timer’s Dance reportedly drew only “a handful of people” each year. Although the character of the event changed, the intent remained the same: commemorating the joy and the resilience of the Punjabi-Mexican people, whose unique culture emerged in spite of — and arguably directly out of — the racially exclusionary nature of 20th-century U.S. immigration policies.

While Punjabi-Mexican communities are not highly visible, the bicultural community retains strong bonds to the unlikely legacy of their ancestors. As a member of the community, Isabel Singh Garcia, explained to the LA Times in 1987: “I don’t want what our fathers did to be forgotten […] I’m Indian and I’m Mexican and I’m 100% American.”