Men are monsters and monsters are men. Through the course of human history, according to Guillermo del Toro, this is the law of the land, the only principle in an unprincipled world. Since his 1993 debut, “Cronos,” a film that considered notions of eternity by turning grandpa into a bloodsucking vampire, del Toro has established himself as one of the great fabulists of our time. The Guadalajara-born director’s complicated relationship with Mexican Catholicism has laid the groundwork for his entire career — many of del Toro’s films deal directly with ideas of religious and political persecution through the same kind of morality tales often told to Catholic children.

With his remake of Edward Goulding’s 1947 noir classic, “Nightmare Alley,” del Toro ditches the monsters under the bed entirely, focusing only on the monster within. All of the director’s signature elements — religious parables, rigid moralizing, gestures towards the supernatural — are given the requisite amount of attention, but the total absence of del Toro’s enthusiastic cannonballs into the otherworldly allows the cynicism that usually rests in the margins of his films to emerge proudly. The lack of goblins and ghouls has not robbed del Toro of his more devious tendencies. For a guy who has made not one but two different films about the Spanish Civil War, “Nightmare Alley” might be his most diabolical, disquieting creation yet.

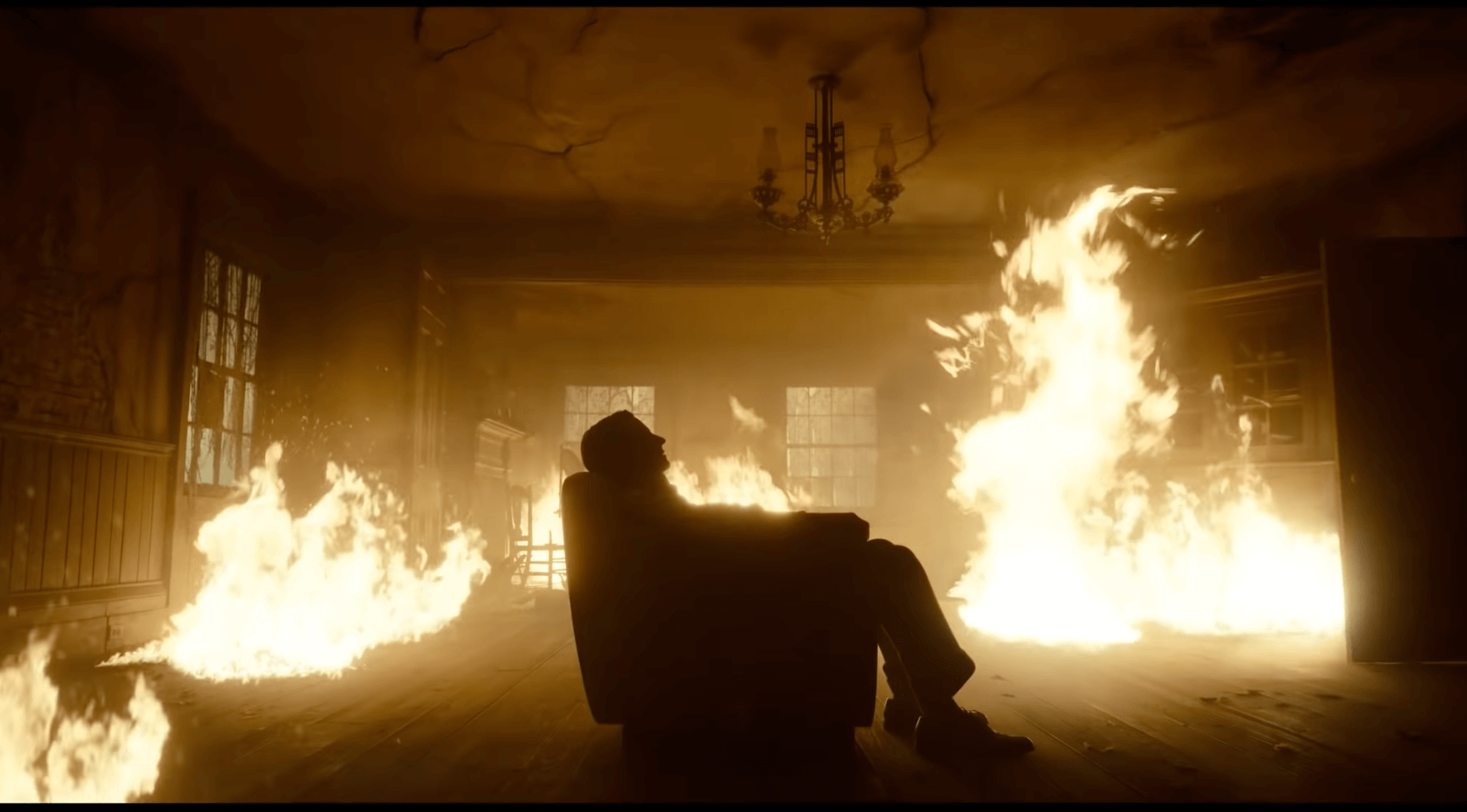

Like the original, del Toro’s “Nightmare Alley” follows low-level carnival worker Stanton Carlisle (Bradley Cooper) to the top of the mountain, charting his rise-and-fall from dollar-a-day huckster to Stanton the Great, a world-famous mentalist (a performer with mental skills and intuitive abilities to interpret body language, behavior, and energy) who rakes in the dough by dazzling the rich, famous, and gullible. Goulding’s 1947 version opens with Stan working as a barker for a traveling act headlined by Mademoiselle Zeena Krumbein (played by Toni Collette in Del Toro’s film) and her alcoholic husband Pete (David Straitharn), but del Toro’s version takes its cues from many a 21st century remake and immediately saddles Stan with dreaded, unwelcome context. From its ominous opening scene, wherein Stan is seen burying a body in his childhood home and burning it to the ground, the film wastes no time cozying up to the recent trope of employing a vague definition of “childhood trauma” as a placeholder for any real depth in characterization.

Despite these updates, fans of the original will recognize much of what comes next: Stan makes his way to the carnival, endears himself to Zeena and Pete, and falls into a secret romance with another performer named Molly (Rooney Mara), always with an eye on the key to Zeena and Pete’s success: a two-person code they’ve developed to communicate during their performances. What’s less recognizable is the one-dimensional sameness with which del Toro has rendered every one of these characters and the story they tell. By refusing to stray too far from the source material while still messing with the mechanics of what worked in the original, del Toro’s “Nightmare Alley” is caught in a structural limbo from which it can never escape.

As a result, watching the film often has the effect of listening to someone talk about their favorite movie — you’re probably better off just watching the movie yourself, but there’s something passably entertaining about listening to them explain it to you all the same. Del Toro blows through all the film’s iconic moments like he can’t wait to get to the next one, but leaves nothing to pick up the slack in the absence of the original film’s patient, tempered pacing. The scene where Stan discovers his talents as a mentalist, for instance, has none of the original’s resonance because del Toro can’t seem to find time in this 150-minute long remake to focus on what gives the scene its momentum. It ends as quickly as it begins, and the festering God complex that carries Stan through the entire film struggles to appear justified.

This frustration with del Toro’s approach extends to more than the passing moments. He recalibrates a handful of supporting players and plot threads to the point of oblivion, distilling characters like Pete — a father, mentor, and friend to Stan in the original — into shells of their former selves, spreading their essence into new unfamiliar faces del Toro has created for the remake (like Willem Dafoe’s Clem Hoatley, owner and operator of the carnival’s controversial geek exhibit) until everyone starts to feel completely indistinguishable. The result has “Nightmare Alley” feeling weirdly sanitized, its gorgeous photography obscuring what is otherwise hollow and unfeeling.

But if we know one thing to be true, it’s that Bradley Cooper has never met a movie he couldn’t elevate simply by showing up, and “Nightmare Alley” is no exception. Cooper embodies Stanton Carlisle without recreating Tyrone Powers’ performance from the original film, painting the character here as the hilariously pathetic little worm that he is. Where Powers still afforded Stanton a certain amount of dignity, Cooper’s interpretation offers no misgivings about just how much of a lowlife Stanton really is, and Cooper clearly revels in the opportunity to play someone so wholly irredeemable. The supporting cast, seemingly comprised of every important character actor from the last two decades, is given decidedly less to do, as del Toro’s screenplay (co-written with his wife, film historian Kim Morgan) is once again too preoccupied with its own machinations to allow the supporting players to live and breathe as more than plot devices.

There are some cathartic bursts of violence that bring Stan’s increasingly uncontrollable feelings of rage to a more satisfying conclusion than was possible in the original, as well as a greater emphasis on his role as a spiritual advisor whose loyal following resembles that of an evangelical preacher, a phenomenon that had already been sweeping the nation when Goulding’s version was released in 1947. But del Toro’s “Nightmare Alley” ultimately doesn’t make much of a case for its own existence, content to circle around the idea of a point before arriving at the predestination laid out in its opening moments. As “Nightmare Alley” inches Stan towards his unfortunate fate, one might notice a certain parallel emerge between del Toro and his doomed protagonist. The film seems to function most successfully as the logical next step for a director who’s clearly working to shed his reputation as being trapped within the fantasy realm. Like Stan himself, it’s possible that del Toro was fated to end up here, remaking “Nightmare Alley” as a prestige picture readymade for awards season. Maybe he was just born to do it.

Grade: C+