I became a “granola” girl while working as a conservation intern during my sophomore year of high school. It was during this experience in the woods that I learned about a few hiking quirks. I was enamored by the term “send it,” used by outdoorsy people to mean “go for it,” and the collages of peeling stickers slapped on hikers’ scratched Nalgenes. It was a shared culture I was excited to be in — even if that culture was mostly white.

That meant that going to any campfire or “granola” get-together, guaranteed that there would be a wiry-haired white guy in his twenties crooning while strumming his guitar. It also meant that I became intimidated by the aesthetics and mannerisms that made a “serious” hiker. I didn’t own any Patagonia jackets and fancy gear, nor did I grow up in a family that went camping or kayaking every summer.

I wanted to excel at being the best “outdoorsy” person I could be. By the time I was finishing high school, I sported Timberland hiking shoes filled with grime. I learned how to make my own granola, and my water bottle was obscured by a medley of stickers from random parks and skateboard brands. Although I couldn’t climb a hill without breaking out in a pool of sweat, I was proud of myself for championing an authentic hiker “aesthetic.”

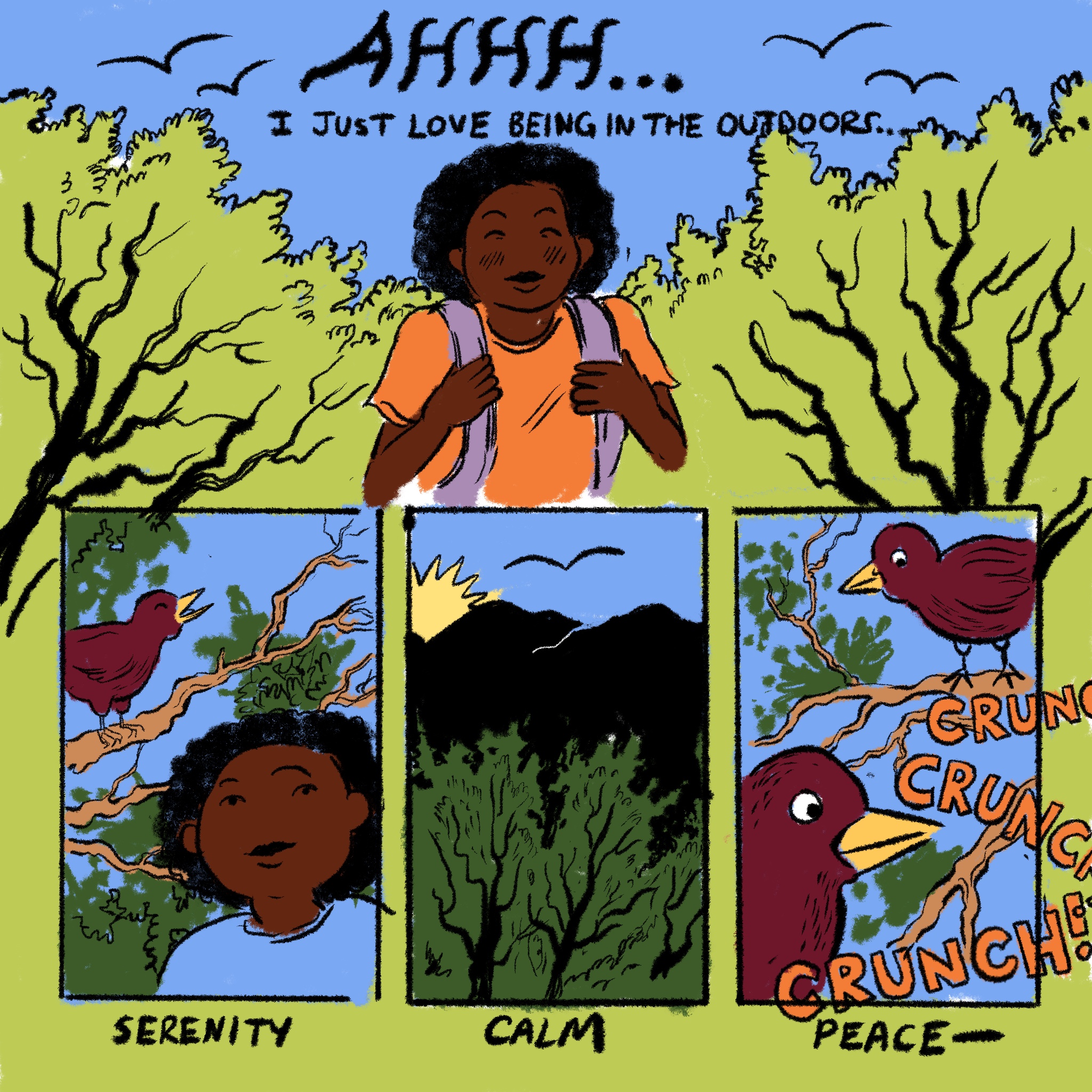

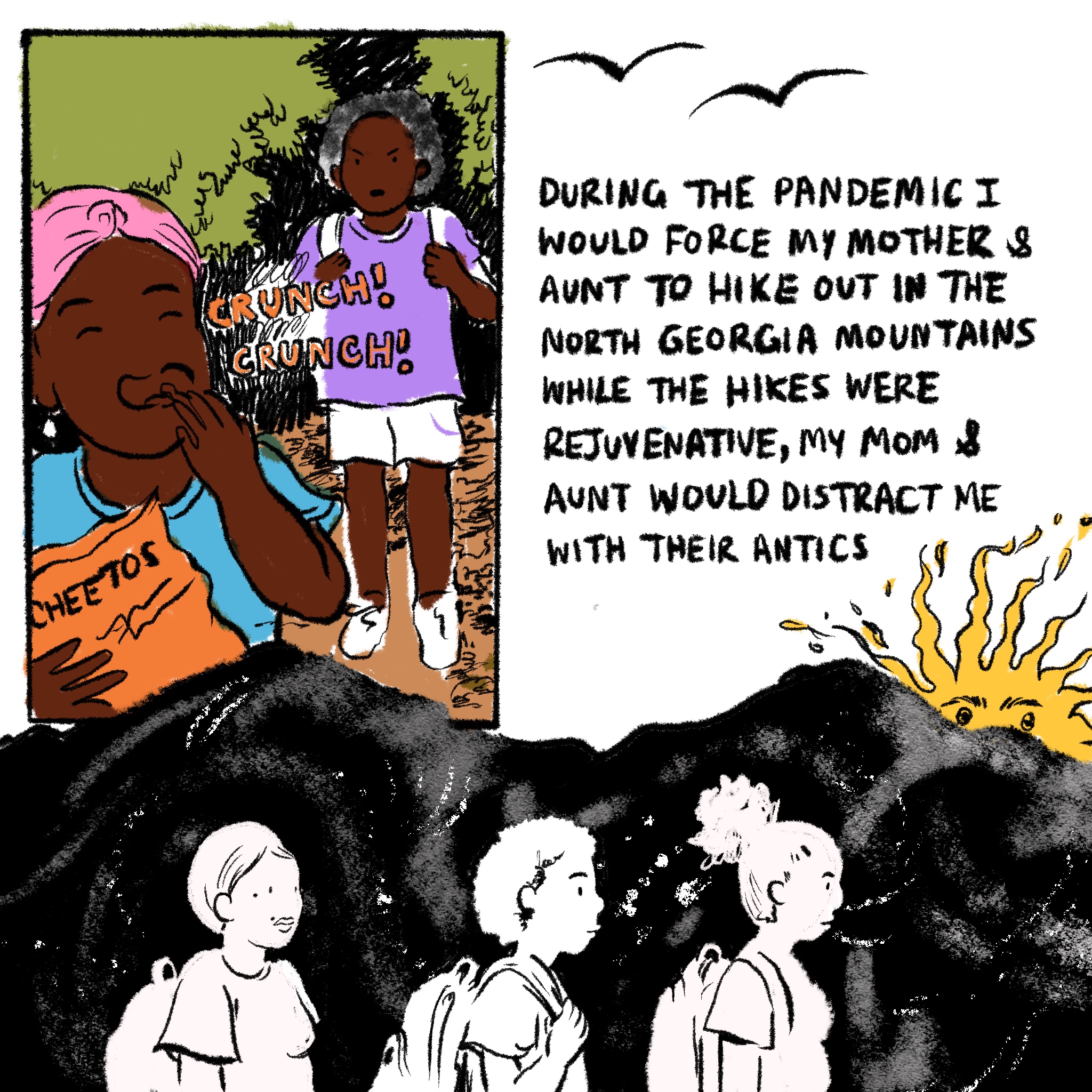

When the pandemic hit, my mother, my aunt and I would go up to the North Georgia Mountains to get away from the stuffy suburbs. To anyone who lives near a real mountain, the North Georgia mountains may appear as mere hills, but to me they were majestic. It was in these mountains that I would hop over knotted roots, under thickets of lush trees. There was a constant humidity in the air that almost felt like a warm blanket, and chirping brown thrashers would flutter over our heads.

But with that serenity came my mother and aunt’s antics. It was during our hikes that I became annoyed by the things I felt didn’t fit into what I had learned hiking was “supposed to be.”

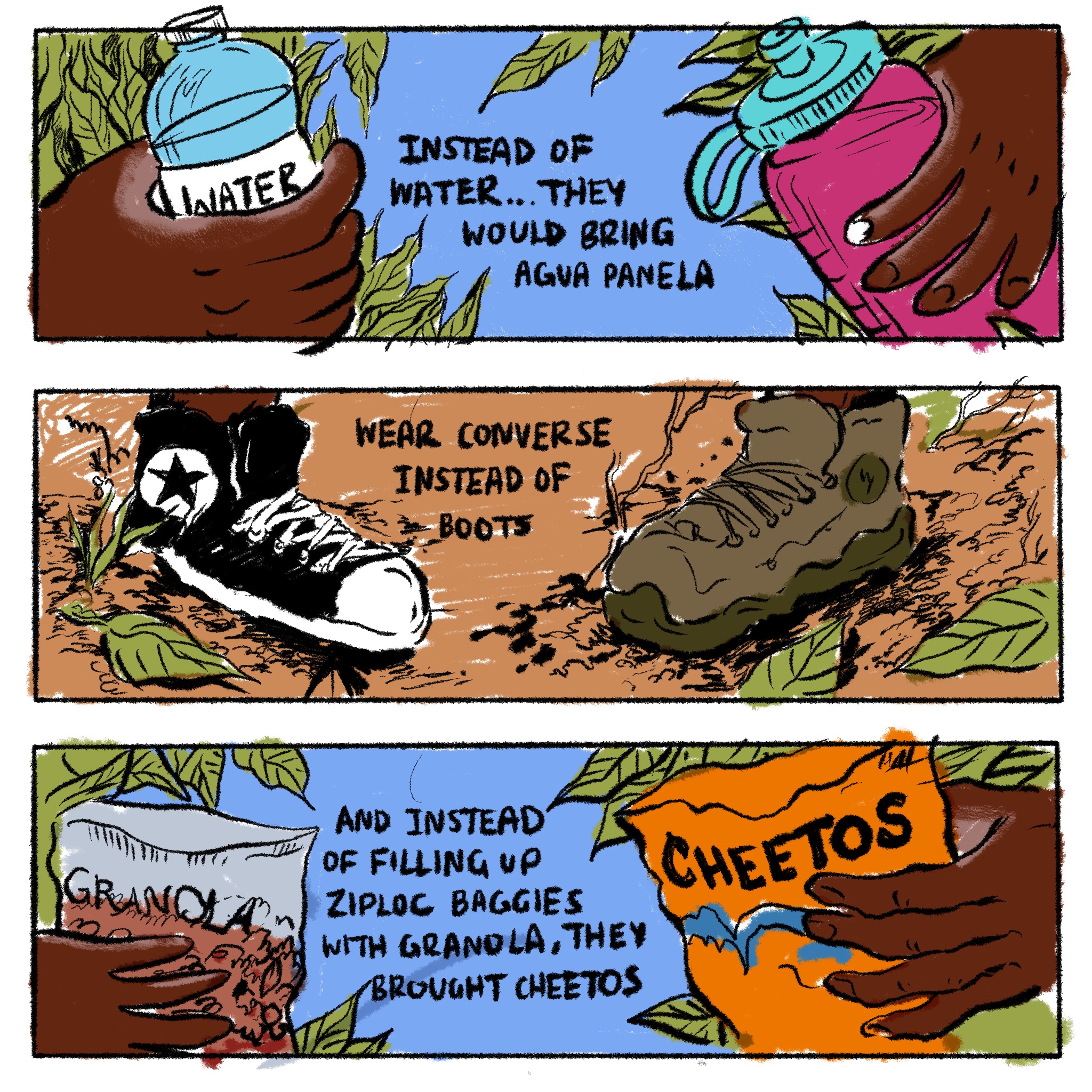

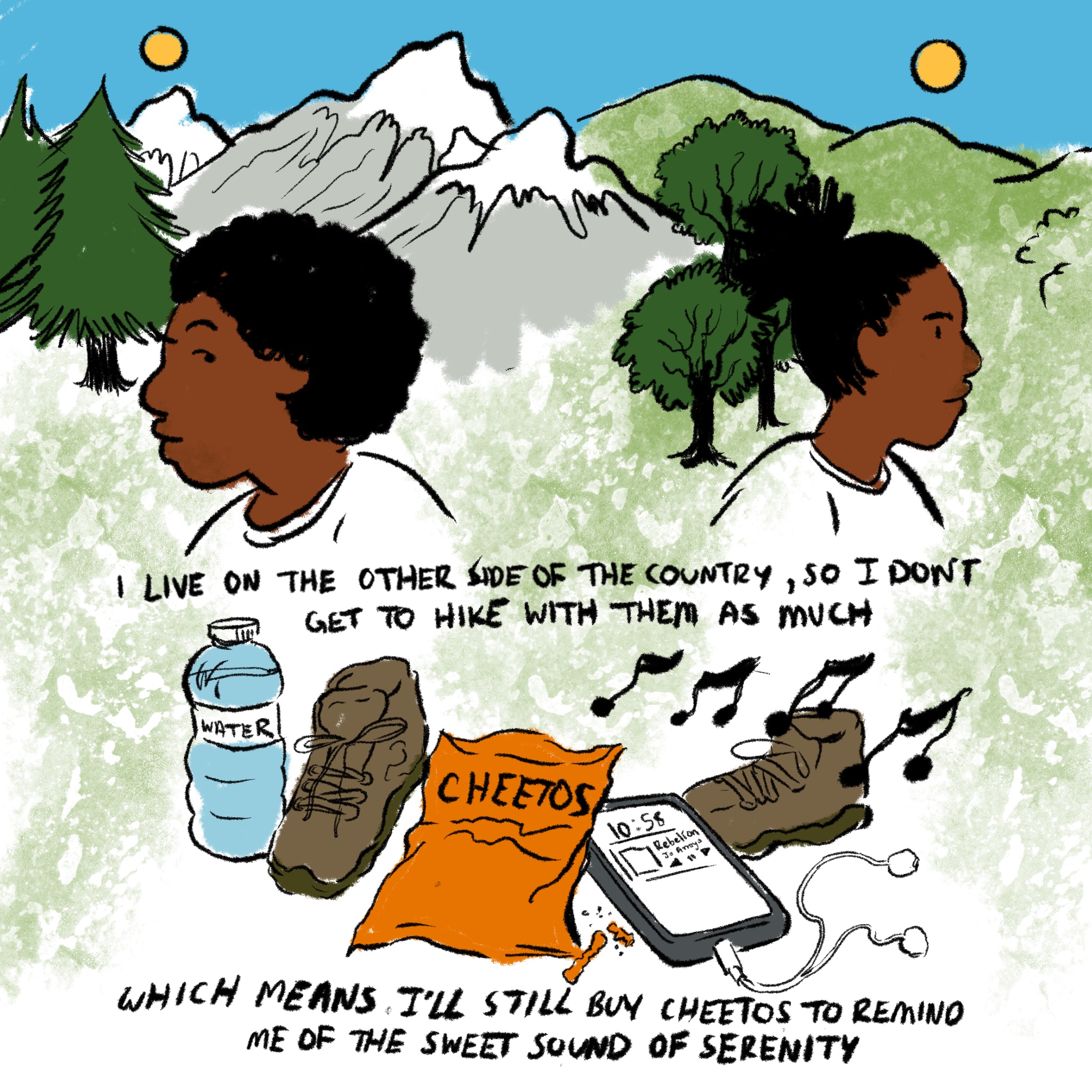

I remember that instead of bringing stickered-up water bottles, they would bring agua panela (a Colombian brown sugar and lime drink) in old apple juice bottles. There was no granola, no nuts, no almonds. Our sole source of energy were the Cheetos and occasional Mentos gum we picked up at the convenience marts that dotted the roads of rural Georgia. And to make matters worse, my mother would play salsa music from her phone as we climbed, Joe Arroyo blasting over the trickling of water from a nearby creek. As we walked, she would pick up various plants and roots from the trail to send to Colombia (which was definitely not super legal). She would sneak them in my backpack or in a Ziploc bag for safekeeping.

I felt a bit embarrassed at the sight of them walking out of parks and hikes with seeds and leaves in their hands, and the sound of them crunching Cheetos along the trail bothered me. To me, we weren’t embodying the image of what outdoorsy people were “supposed” to be like, nor were we aligning our habits with the natural landscape.

Later on, once I started hiking with other people, I saw that they had their own little quirks too. And I realized how intolerant I had been of my mom and aunt.

There’s a history of who can and can’t occupy natural spaces. Some of the early ideals advocated by preservationists were the concepts that recreational natural landscapes were meant to be pure and undisturbed terrain. Of course, this ideal was flawed, as indigenous people had been coexisting with the natural landscape long before the United States had seized so much of their land to create national parks.

Nonetheless, nature was supposed to be pure and clean, safe from the peril of man and his dirty habits. As a result, we’ve been preached a singular ideal of what coexisting in nature means. For outsiders, there is often a switching on and switching off, a kind of entering into natural spaces with a detachment of oneself, rather than existing authentically.

This has meant that often people of color have been judged for not behaving in nature correctly. I remember my mentor telling me that when she worked in Yosemite, people would leave Yelp reviews of certain campgrounds or recreation areas with complaints that people were playing soccer and blasting loud music. This, of course, was coded language for someone frustrated by how people of color were “staining” the pure fabric of the natural landscape.

That’s the issue with this pressure to play the part of an “outdoorsy person.” There’s a cultural script laid out for you that also pushes the ideals of whiteness in nature. While some people may have grown up skiing or kayaking, Latinx or Black folx may have grown up interacting with the outdoors a bit differently but with just as much appreciation. Instead of going white water rafting, outdoor activities are often made more communal, like having cookouts near the lake at a local state park, or going fishing, or even just playing soccer on campgrounds near Yosemite.

It wasn’t until later in life that I realized that these little customs my aunt and mother did were their way of making themselves more comfortable, a way to exist authentically in the new and weird world of the woods. The salsa music, the agua panela, and even the plant picking were a means of interacting with the landscape. Instead of the salsa music obscuring the sounds of nature, the music was blending with the sonic environment of the woods to create a new rhythm. And instead of my mom and aunt being weird plant ladies, they were showing their adoration of the terrain we were visiting. I remember how they would smile and take pictures when they found a plant that delighted them.

While I hope that they stop picking plants to send to Colombia (I fear the spread of an invasive species!) I think nature is the perfect platform to cease the performance. Nature should be a place to embrace the imperfections, the oddities, the weirdness, and yes, the Joe Arroyo salsa music. I think the birds like to sing along to salsa music!

Arantza Pena Popo is a queer cartoonist and illustrator in based in Los Angeles, CA.