Before going to Cosme, I never doubted the efficacy of food writing. I thought it was possible to describe flavor, to capture it with the cincture of language. But as I had a bite of Cosme’s corn husk meringue, I was struck by its overwhelming density of flavor. Within the luscious and subtle sweetness, there was the purest essence of corn, and I encountered the futility of the word.

I had read restaurant reviews to prepare myself for Cosme’s famous dessert, trying to conceptualize the “vegetal sting” and the dish’s balance of crunch and silkiness but was left in disbelief as I finally tasted the meringue. The dessert was the actualization of corn, and responsible in large part is Masienda, a brand dedicated to sustainably farming heirloom corn varieties. And it’s not only at Cosme — the brand provides corn for numerous fan-favorite restaurants, such as For All Things Good and Atla in New York and Frontera Grill in Chicago. Masienda’s founder Jorge Gaviria’s secret is simple: “We are an entire supply chain built on integrity and the pursuit of integrity.”

Photos by Graydon Herriott

The genesis of Masienda? An overheard conversation at a dinner party. Jorge Gaviria, then a chef under Dan Barber at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, was checking coats for a one-off culinary event at the restaurant, where various trailblazers in the culinary community were in attendance. The topic of discussion was how to source for quality instead of efficiency and yield.

This principle defines the mission of Blue Hill. Sourcing their ingredients from their in-house farm, Blue Hill maximizes taste by centralizing biodiversity, organic agricultural practices, and fresh ingredients. Their actions and philosophy were developed in response to the rising industrialization of food, to the trends which have compromised taste, nutrition, public health, and environmental sustainability but have also broadened food access.

Photo by Noah Forbes

Photo courtesy of Masienda

Soon after this event, in 2014, Jorge Gaviria took the lesson to heart: great food needs even better ingredients. He flew down to Oaxaca, and on this research trip, Gaviria realized that he had only known one type of corn, American sweet corn. In Oaxaca, he tasted a variety of corn that, due to its beta carotene, had orange kernels and tasted like butternut squash. One hour later, just miles down the road, Gaviria had a piece of creamy white corn that had, as he described, “less expression, but a beautiful texture.”

The varieties of corn that he tasted astonished him and presented an opportunity. He compares this revelation to another culinary commodity, coffee. In Gaviria’s eyes, corn was destined to follow coffee’s three waves, the path from a neglected product of mass consumption to developing a small and dedicated level of niche connoisseurship.

As a result, Masienda works with small-scale, sustainable farmers in Mexico. Instead of using industrial techniques, these farmers are indebted to environmentally-responsible indigenous agricultural practices, specifically the Aztec milpa system. At its most basic level, the milpa system is a symbiotic intercropping system where corn is grown alongside nitrogen-fixing beans and squash, which prevent weed growth and climb the corn to support leaf growth. This mutually beneficial relationship results in nutrient-filled soil, thus fantastic flavor.

But Masienda is not solely fixated on the preservation of traditional agricultural systems. They do not want to control farmers by prescribing farming practices. Instead, they serve as a tool to support farmers, allowing farmers to adapt and regain a sense of agency. Their business model is simple: grant the three-million subsistence farmers in Mexico the opportunity to sell their surplus at a local premium. There is no hyper-capitalist impetus to increase individual productivity, to produce at economies of scale. Instead, they are a humble buyer attempting to pay fair prices for those who want to work with them. Ultimately, they are a relatively small venture, working with only two-thousand farms, all of which approach their relationship with Masienda differently.

Photo courtesy of Masienda

Masienda does not attempt to revolutionize the entire agricultural industry but wants to offer an alternative. As Gaviria put it, Masienda is “a complement, not a competitor.” Of course, Gaviria still understands the detrimental environmental and nutritional impacts of contemporary farming but also realizes its positive social impact, complicating the story. Gaviria stated, “The convenience provided by Maseca and Gruma opened up a lot of doors for people.” Gaviria claims that this convenience liberates, that people are freed from the kitchen and can pursue what they want, an underrecognized boon of food-industrialization. As a result, Masienda markets itself with a level of humility: they are not the self-aggrandizing upheaval. Instead, he gives people, both the farmer and the consumer, a choice. And to Gaviria, the consumer, in this case, the home cook, is not to be overlooked. Masienda is not solely for the high-end restaurateur and the sous chef. He wants to allow the home cook the ability to choose health and taste, selling four types of masa harina and eight varieties of corn.

Photo by Graydon Herriott

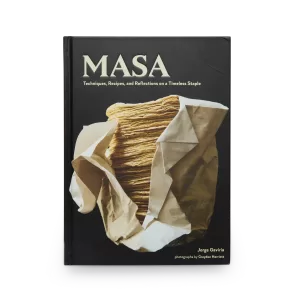

Now, eight years after founding Masienda, Gaviria finds himself in a place he never imagined, publishing a cookbook. Masa: Techniques, Recipes, and Reflections on a Timeless Staple is the first seminal cookbook on masa, a topic that superficially seems niche and inaccessible. When posed the question, “Why corn?” Gaviria responded, “We’ve talked about politics, we’ve talked about food, olfactory qualities, travel, education, people, all of that is innovatively tied up in corn, and to me, that is infinitely stimulating. It’s not just corn. It’s not just masa.”

When performing research for the book, Gaviria was not only shocked by the interconnection between corn and the non-culinary, for example, in social movements such as Sin Maíz No Hay País, but by the gaps in the historical and cultural archives. First, there was no corpus; second, many of the traditions were solely oral and hyper-regional; and third, essential pre-Colombian corn knowledge was lost in the cultural genocide of colonization. Gaviria was surprised by this contradiction, that despite people globally indulging in tacos, thus masa, it remains understudied.

Photo by Graydon Herriott

Masa: Techniques, Recipes, and Reflections on a Timeless Staple is devoted to sharing how best to prepare and respect corn. Gaviria’s cookbook thoroughly explores how kernels become masa, deliberating on the intricacies of grinding and the difficulties of cooking with cal. The book includes explanations of masa’s applications as well as traditional and contemporary recipes. The ten recipes for contemporary masa applications pay homage to the Modern Mexican culinary movement, which attempts to balance tradition with innovation. Born from this fusion are dishes such as shrimp and masa grits, lamb birria with mass gnocchi, and masa samosas. There is an inherent cosmopolitanism in these dishes, and Gaviria, when constructing these recipes, made sure to “interrogate the difference between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation.” Gaviria perceives our current world as one in which “borders are becoming increasingly illusory,” and, using this perspective, he captured a spirit of interconnection and cross-pollination.

However, Masa: Techniques, Recipes, and Reflections on a Timeless Staple is primarily devoted to capturing the complexity and wholeness of the Mexican culinary tradition. Gaviria exemplifies this dedication with his treatment of atole, a corn-meal beverage. When describing the recipe, Gaviria first begins by sketching out its history, specifically, the Nahuatl etymology and its prevalence in the indigenous Mesoamerican diet. Gaviria then proceeds to sketch the basic recipe of the dish before diving into how regional contexts transmute atole, for example, how in the state of Tabasco, they ferment the masa. By rooting his text in the regional traditions, he displays the beauty and complexity of Mexican cuisine but also leaves a space for experimentation. This tacit invitation empowers the home cook to take these recipes as not only cultural anchors but jumping-off points. Ultimately, Gaviria envisions the masa chef akin to the baker, that each family will intricately hone their technique, iterating over time to create their perfect tortilla.

Image courtesy of Masienda

Jorge Gaviria’s cookbook Masa: Techniques, Recipes, and Reflections on a Timeless Staple was published on September 13, 2022. Masienda also sells its high-end restaurant-quality corn to home cooks through their website.