Cuando en una noche de Verano,

Yo en vuelo de un avión, cruzando el cielo del

(Polo Norte,

Para dirigirme al Lejano Oriente…

En un sueño te vi…

Tu cuerpo manchado de sangre!!!

Y tu bello cabello negro, largo, estaba cortado!!!

Sentada en una Flor de Loto subiendo al cielo,

Como la Virgen Buda “Kum Yim”.

Born in Jinotepe, Nicaragua in 1955, Arlen Siu Bermundéz is remembered as an icon of the revolutionary Sandinista youth. The daughter of Rubia Bermúdez and Mankuey “Armando” Siu Lau — a former soldier in the Communist Revolutionary Army who migrated from Guangdong, China in the late 1940s — Arlen spent her childhood in Jinotepe painting, dancing and playing the guitar. Per her father’s recollection, Arlen was uniquely interested in their family’s Chinese heritage: when her father refused to teach her his native tongue, she defied him and pursued Cantonese lessons from her grandmother Luisa instead.

As a student in Jinotepe’s La Escuela Normal de Señoritas, Arlen hoped to become a teacher, aspiring specifically to combat illiteracy in rural Nicaragua. But in continuing her studies at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua (UNAN) — where she also sang with Marlene Alvarez and the band Grupo Pancasán — Arlen grew deeply involved with the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional — the Sandinistas — a revolutionary socialist party emerging out of the student movements spreading across Nicaragua’s universities. The Sandinistas took inspiration — in ideology and in name — fromr Augusto César Sandino, the revolutionary combatant who successfully ousted U.S. occupying forces from Nicaragua between 1927 and 1933.

Sandino’s assassination in 1934, at the hands of the National Guard of General Anastasio Somoza Garcia, proved equally consequential. Somoza would proceed to lead a coup d’état two years later, establishing a Somoza family regime that would maintain control of the country for the next 42 years. In this time, the Somoza family accumulated immense wealth through bribery, land grabbing and corruption. By the 1970s, they owned nearly 25 percent all Nicaraguan land. And after a 6.2-magnitude earthquake effectively leveled Nicarauga’s capital, Managua, in December 1972, the Somoza family and their National Guard embezzled millions of dollars in international aid intended to rebuild the city, leaving thousands of Nicaraguans to fend for themselves.

The Somoza regime’s corruption in the disaster’s wake inflamed resistance to the dynastic government. Strikes and demonstrations spread across the country, and the ranks of the Sandinistas swelled with young people like Arlen.

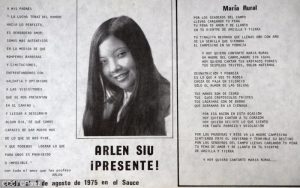

As the Sandinistas’ popular support grew, Arlen rose to prominence chiefly as a political songwriter and musician. Most famously, Arlen penned and performed “Maria Rural,” a song celebrating rural Nicaraguan women as “madre[s] del campo/madre[s] sin igual,” earning her a reputation as the voice of Nicaragua’s attendant women’s movement. Arlen also composed several essays of Marxist and feminist analysis; in her lyrics and writings her alike, she condemned sexual violence and disappearances committed by Somoza’s soldiers and highlighted the central role of peasant women in Nicaragua’s past and, with luck, its revolutionary future.

Arlen visible’s role in the Sandinista movement made her an obvious target of Somoza’s government. In August 1975, two years after joining the Sandinistas, the National Guard ambushed a Sandinista training camp in the mountains outside of León, killing Arlen and several of her comrades.

Source: https://www.antiwarsongs.org/canzone.php?id=43629

In his mourning, Arlen’s father published the poem “El Gran Dia Para Arlene” in her memory:,

When you left for that great destiny,

you left me your guitar, your unfinished painting,

your prophetic poem, and the book Juan Salvador Gaviota

so that I could feel your love beyond

the heavens and earth.

That mourning extended well beyond Arlen’s immediate family. Months after Siu’s death, students in Jinotepe continued to carry her photograph alongside Sandinista flags while protesting the National Guard. One particular image, by the photographer Susan Meiselas, captures well the students’ furrowed brows and rasied fists — a ceremony of defiant grief.

Arlen’s legacy persists to this day, largely through poetry and song — in the work of other Nicaraguan artists as much as her own oeuvre — ensuring that Arlen’s revolutionary song lives on.

Source: https://medium.com/@anagsiu/la-mul%C3%A1n-que-nunca-regres%C3%B3-18cf6738716d