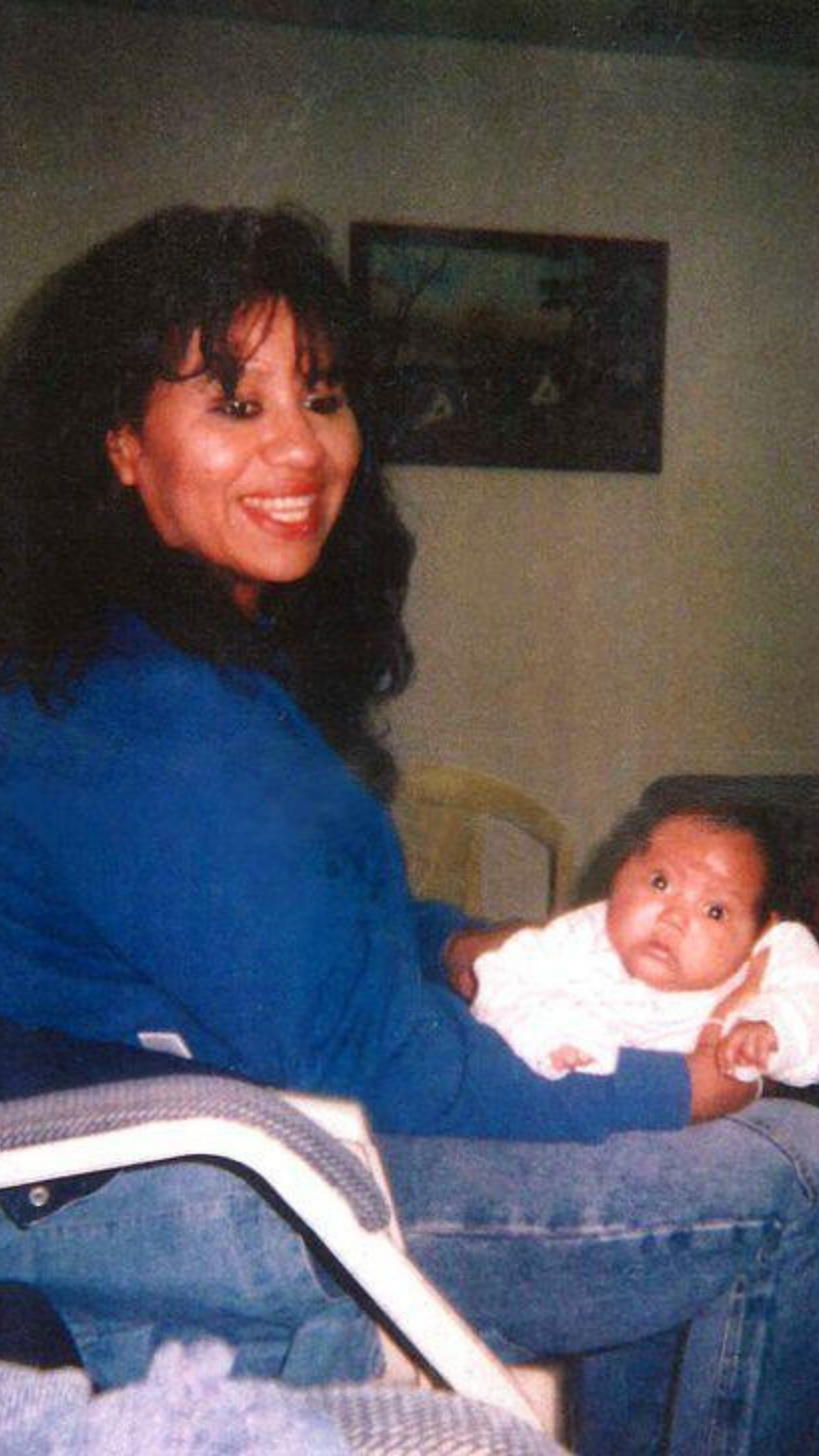

A little over a year before Casey Anthony caught national attention in 2008 for allegedly murdering her young daughter Caylee, a woman named Melissa Lucio was fighting for her life in a Brownsville, Texas police interrogation room. Cameron County Sheriffs had accused Lucio of murdering her two-year-old daughter Mariah, the youngest of her seven kids living in the house at the time, who had fallen down a flight of stairs and died in her sleep two days later.

Police interrogated Lucio for five hours the night of Mariah’s death, and Lucio gave law enforcement what many activists and experts consider a coerced confession. On July 30, 2008, a little more than a year after her arrest, the Mexican-American mother of 12 was sentenced to death. After spending the last 15 years behind bars, Lucio is now awaiting execution, scheduled for April 27 of this year. She is the first Latina woman sentenced to death in the state of Texas.

The question of Lucio’s innocence has been the one driving many of the conversations surrounding her case. So, too, has Texas’ treatment of its inmates. The latter has been a topic of conversation for reformers and revolutionaries working to change the way millions of people behind bars are treated, not just in Texas, but throughout the United States. Statewide labor laws that permit free and forced inmate labor in Texas are akin to legal slavery, and inmate activists have been working tirelessly to expose the conditions that allow it to continue. Given what we now know about how Texas’ criminal justice system operates, Lucio’s imprisonment presents itself as a miscarriage of justice that goes far beyond just a singular case.

Through a combination of sources that range from the 2020 documentary “The State of Texas v. Melissa” to contemporary activist groups like The Innocence Project working to reform and revolutionize the prison industrial complex, we hope to get a better understanding of why Lucio’s case is as horrifying as it is commonplace. Though there are limitations in terms of scope and access to information regarding Lucio’s case, we hope to at least paint a better portrait of the penal system in Texas, and the steps taken to ensure Lucio’s imprisonment and impending execution.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

Renewed interest in Lucio’s case over the last couple of years has led to widespread pleas for her release and a greater focus on the seismic blind spots of the American justice system. The 2020 documentary “The State of Texas vs. Melissa” offered a beat-by-beat breakdown of Lucio’s case and the numerous occasions where those tasked with uncovering the truth missed the mark. In a March 7th spotlight on “Last Week Tonight with John Oliver,” Lucio was one of many examples of wrongly convicted individuals like Ricky Kidd, Lamar Johnson, and Edward Lee Elmore, some of them still behind bars even after exonerating evidence had come to light. Lucio, who is expected to serve the entirety of her sentence and die for what she was accused of, is stuck in the worst kind of purgatory; she’s never been proven innocent, but she wasn’t exactly proven guilty either. “I could hear them out in the hallway, deciding what to charge me with: injury to a child or capital murder. They couldn’t decide,” said Lucio in the 2020 documentary.

Lucio’s case is striking in that it has very little to do with her innocence. Although there were no witnesses, there are conflicting reports from a handful of her children, some of whom corroborate the stories of Lucio’s abuse while others deny them in their interviews for the 2020 documentary. Her daughter, Selina Flores, runs a TikTok account dedicated to refuting much of the narrative established in the “Texas v. Melissa” documentary. The initial investigation makes it impossible to know what happened the night of Mariah’s fall. However, what continues to be so painfully clear to Lucio’s supporters is that she does not deserve to die, and the state of Texas is determined to make sure she does.

Like many wrongful convictions, Melissa Lucio’s trial begins with an overzealous public servant. In this particular case, it was ex-district attorney Armando Villalobos, who was sentenced in 2014 to serve 13 years in federal prison for bribery and extortion. At the time of Mariah’s death, Villalobos was running for re-election with a tough-on-crime stance that promised harsher sentencing. The Lucio case suddenly became his best chance to convince potential voters that he was a man of his word. Now, he’s serving more than a decade in prison following a prosecution by assistant U.S. attorney Michael Wynne. “Armando Villalobos profited from the place he was in,” Wynne said in the documentary, “and that was in the middle of a drug cartel.”

A 2022 report by The Innocence Project revealed that Lucio’s trial failed to properly shed light on information that may have led to her exoneration: her daughter’s disability, the aggressiveness of the arresting officers during their investigation, and her lawyer’s refusal to call her children to the stand. Consider the fact that her daughter was born with a mild disability that caused her foot to turn inward. She tripped often as a result, making it all the more likely that she could have fallen down the stairs. Or that officers, relentless in their assertion of Lucio’s guilt, questioned Lucio until 3 a.m. on the night of her daughter’s death and repeatedly told her that they knew she killed Mariah.

In “Texas vs. Melissa” Lucio’s original attorney, Peter Gilman, defended his refusal to call any of her children to the stand, and said, “I didn’t feel like any of the children would be helpful,” during his interview. One of Lucio’s children, John, recently said of Gilman, “[he] does not want to respond, because he knows what he did. He knows exactly what he did, he left out many [pieces of] evidence.” He continued, “Watch the film because, inside the film, there’s a bunch of evidence that was not utilized in my mother’s trial.” A recent article from The Innocence Project confirmed the critical flaws in her trial: “A panel of federal judges on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed in a unanimous three-judge opinion that Ms. Lucio was denied the right to present a meaningful defense.”

At the time of Mariah’s death, the Lucio family was living in Harlingen, Texas, a city that, as of 2017, was estimated to have a 29.8% poverty rate. As of 2020, the population of Harlingen was more than 80% Latino. An article from the American Action Forum reveals that those in poverty are three times more likely to be arrested than those who are not, and additional factors like race and histories of drug abuse only serve to compound the odds. That Lucio was a Latina woman who had a drug problem and was living with her children in poverty made her chances against Cameron County law enforcement next to none. In greater Cameron County, home to the cities where Lucio lived for most of her life, the poverty rate is estimated at 31.2%, with a population that’s 90% Latino.

The Prison State

To put into perspective just how aggressively the state of Texas pursues convictions across the board, it’s worth noting the state’s rate of incarcerations, which is nearly 850 for every 100,000 residents as of 2017, outranks the rest of the US and the rest of the world in prison population per capita. As of 2020, Latinos alone make up 38% of the population in Texas and 33% of its incarcerated population. By comparison, Black people in Texas make up just 12% of the population and 32% of its inmates. Not only are there racial disparities in the sentencing process, but reports on the conditions in Texas facilities also paint a grave portrait of life behind bars: cramped cells, guards who turn off the water as punishment, and sweltering summer heat are just some of the conditions to which inmates are subjected.

According to a 2016 report in Cameron County, there were nearly 7,100 people—out of 425,000 total— who required the use of court-appointed representation; this translates to roughly 6.5% of Cameron County’s impoverished population. More than 1% of the county’s population is currently on parole. Compared to Brazoria, a similarly-sized county of about 390,000 where whites make up half the population, the jail population drops from nearly 1,400 in Cameron to just over 800 in Brazoria, a nearly 40% drop in a county that’s only 10% less populous.

As of 2021, it’s estimated that Texas generates roughly $70 million per year through forced prison labor for both public and private diversions. Prison labor is a multi-billion dollar industry across the nation. In Texas, the prison population “manufactures goods and provides services for sale, on a for-profit basis, to city, county, state and federal agencies, public schools, public and private institutions of higher education, public hospitals and political subdivisions,” which is standard practice across the US, according to an article in the San Antonio Express News. What’s unique to inmates in Texas is that they are not able to opt out of unpaid labor, and suffer negative consequences if they do refuse their work assignments. The state’s penal system regards its impoverished population more as a source of free labor than it does as a community of human beings.

And Justice For All

In the event of her death, Lucio will be made into a martyr, and an embodiment of all that’s wrong with the justice system. Cameron County, Armando Villalobos, and the state of Texas used her as an example. She’s living, breathing proof that nobody is safe from the long arm of the law in Cameron County, or the entire state. If a single mother of 12 can be put on death row after a trial based on tenuous factual connections and withheld information, nobody is safe.

For a state where prison labor is both mandatory and unpaid, and the state in question uses a lot of it, Cameron County law enforcement makes its point very clear: it can and will put away anybody it wants. It seems that being poor is a crime in Cameron County, punishable by forced labor and inhumane conditions inside the facilities. Drug addiction is not considered an illness, but a crime. Black people and Latinos continue to live in fear of a system that is fundamentally designed to keep them behind bars. Police misconduct is not treated as a blight on law enforcement in America, but as an effective strategy to carry out the agendas of the for-profit prison industry.

If Lucio doesn’t deserve to die, who else is being victimized by Texas law enforcement, the state’s judicial system, and the federal courts? Her case is the exception insofar as it is an exceptionally egregious instance of coercion and wrongful conviction, but cases like hers are evidence that the system is working as intended, for everybody but the inmates.

When activists, reformers, and revolutionaries talk about racial bias within the justice system, this is what they mean. The concentration of poverty and “criminality” in places like Melissa’s hometown aren’t bugs in the system, they’re features. The question isn’t whether or not Melissa should be brought home — she should — but how to navigate meaningful change within a judicial system that would allow this to happen in the first place.