Women’s healthcare is complex, but building an equitable medical system is straightforward: information, access, and community are essential to make it happen. I learned this from my health journey and that of my grandmother.

When I was 32, I learned that my grandmother had died of complications from an abortion, a procedure considered illegal when she received it in 1960s Brooklyn. As a child I believed she had been killed by an asthma attack. My grandfather never shared more details, and I never asked. Could it have been a friend who performed the abortion? Someone known in the community for helping women with “issues”? Did my grandparents hold hands as they nervously walked the streets of Bushwick, whispering to each other as they tried to find a safe place for her to terminate her pregnancy? I may never know.

“Illegal” is a dangerous label. It forces people into secrecy. In the case of my grandmother’s abortion, that meant terminating a pregnancy without receiving safe care. She had already given birth to two kids but decided to terminate this third. While at the time “legal” medical abortions were given to white women of means in New York City on a limited, basis, my grandmother, a working-class Puerto Rican, didn’t have that option.

Photo Courtesy of Ivelyse

Sixty years later, women of color still don’t experience the unfettered access to abortion that Roe v. Wade claims to protect. Where we live, how much money we make, and how we interact with each other either help or hinder our access to reproductive services. We don’t have to poke too far into U.S. history to see that Black and Brown’s bodily and reproductive autonomy infringements extend beyond abortion.

In my late twenties, I learned the dark history behind birth control: from the 1930s to the 1960s, birth control supporters argued that population control was the solution to poverty and the systemic oppression of poor Black and Brown communities. Sterilizations, known in Puerto Rico as “la operación,” were performed in several ways, including while some women recovered in hospital beds after giving birth. In these cases, patients were surgically sterilized without informed consent and given misleading information about the reversibility of the procedure. By the 1960s, one-third of the Puerto Rican female population was sterilized. Within three years after my grandmother died of her procedure, the Puerto Rican government repealed Law 116, the 1937 law which had allowed for forced sterilizations.

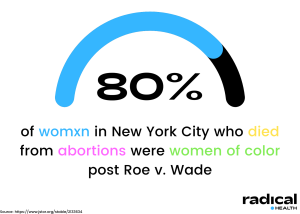

Even though Roe v. Wade changed federal abortion law starting in the 1970s, abortions often weren’t available, accessible, accepted, or safe for women of color. A study from 1976 noted that within three years of the Roe v. Wade decision, 80% of women in New York City who died from so-called “clandestine abortions” were women of color. Even after Roe v. Wade, women from affluent white communities would still face fewer risks and lower mortality rates compared to communities of color. Whether the procedure was deemed, “legal” didn’t guarantee safety for Black and Brown women. As Steven Polgar and Ellen S. Fried detailed in their article The Bad Old Days, “Poor and minority-group women were virtually precluded from obtaining safe, legal procedures, the overwhelming majority obtained by White women in the private hospital service on psychiatric indications.”

Nearly 50 years after Roe v. Wade, the United States Supreme Court and many conservative states are preparing to overturn the historic decision. Much like my grandmother, those communities continue to be impacted by the decisions of a group of primarily white and male legislators. These laws disproportionately impact Black and Brown folks’ reproductive health and their access to safe procedures.

It is difficult for many people to obtain quality healthcare, but most especially women of color. Contemporary discussions around healthcare access must address the factors that disproportionately impact this group.

Finding Community in My Healthcare Journey

Long before I learned about my grandmother’s life-ending abortion, I had my first gynocological appointment. Seniors in high school, my friends and I rode the subway for over an hour from the Bronx to Manhattan for access to birth control. The quality of care available to us in the Bronx was different from Manhattan, and we wanted to make sure that nobody in our tight-knit community would recognize us and tell our parents what we were doing. The fear of la chancla is real.

We were all nervous and tried to hide it, joking loudly with each other as we sat in the waiting room, glad to be there together. We all knew that getting on birth control was a wise decision. Sitting with my friends in that waiting room, I felt comforted by the power of my community.

According to a CDC report, Latino folks are two to three times more likely to develop STIs like gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis than white folks. In addition, Latinx teenage pregnancy rates are the highest of all other ethnic demographics in the U.S. It’s easy to take these statistics at face value without understanding the greater context around accessibility.

The lack of readily available birth control in my community meant I didn’t have the time to make the three-hour round-trip subway ride to return to Manhattan every three months to renew my prescription. As a result, I got pregnant not long after my last pill ran out.

A few weeks after the pregnancy test showed positive, I shuffled into Planned Parenthood, petrified. After I checked in and got my intake form, I glanced around at the other women sitting quietly and sat down. A tear rolled down my cheek. I suddenly felt like I couldn’t breathe.

One of the women sitting across from me patted my knee and asked if I was okay. We made small talk, and I learned she was also there for an abortion. Other women in the waiting room joined in. We formed a shared sense of camaraderie. What had been a scary and lonely situation turned into a beautiful memory. I walked in alone, but I walked out with community.

Healthcare is complex; my journey goes far beyond the two situations I shared with you today. In writing this piece, I could have picked any angle to discuss, from conception to breastfeeding, IVF to abortion access, and endometriosis to vaginal discharge. Abortion is a personal choice, and a polarizing topic among certain groups. Regardless of personal stances on abortion or sex education, or other health experiences, information and access for everyone are essential to an equitable medical system.

At this time, the future of the United States’ policy on reproductive care and access is uncertain. However, I know we don’t have to endure our healthcare journeys alone.

We can communicate with each other. When the sterile, cold atmosphere of the healthcare system was isolating, I found solace in the community and the lived experiences of others who had gone through what I have. These experiences shaped my work today with my healthcare organization, Radical Health. Who else is there to look after our communities, if not us? We show people how to build, develop and tap into their community so that they “don’t have to Health alone.”

If you don’t have a community at home, you can build it for yourself: whether you’re walking in and making new friends in the waiting room, chatting with the nurse on your way to the exam room, or even just posting to a Facebook or Reddit community online. When we organize, we help inform ourselves and others. So if you are facing your healthcare journey alone, remember that a community can support you when you are ready.

##

Ivelyse is a visionary healthcare strategist and abolitionist building community at the intersection of mobile health and equity. She is the founder and CEO of Radical Health and a Commissioner on the New York City Commission on Gender Equity. Radical Health addresses health equity through community and tech and combines meaningful conversations with AI enabled tech that helps people understand what’s going on during a visit, build trust, and improve self advocacy.