“Sana Que Sana” unveils an unfortunately common story in Latinx heritage, one afflicted by machismo and shame. It follows director Gabriella Aguirre’s grandmother as she collects the pieces of a shattered legacy, after learning that her husband of fifty years had been leading a secret life. Set in Cali, Colombia, Aguirre allows us an intimate view into her grandmother’s experience of contending with the idea of “happily ever after.” We are left to ask ourselves, can love last forever?

The short film premiered September 16th, 2022, at the New York Latino Film Festival, which showcases Latin American filmmakers in all genres. It was later showcased by the New York Women in Film and Television organization at the Hamptons International Film Festival, where Aguirre was recognized for her early-stage achievement among several other emerging directors. Lush imagery, including symbolic items like “sugar cane” – a staple in the landscape of Cali – helps weave together the fabric of this film, and tell a painful story of love and loss.

LATINA caught up with the film’s director Gabriella Aguirre for an interview, and via a selection of images from the film, Aguirre gives us a view into her creative process.

THALIA: Tell me about what inspired this film, what kind of questions were you asking yourself?

GABRIELLA: Going into making this film, I was so curious about what healing could look like for my grandmother. At the time, my parents were also separating after nearly thirty years together. My ideas of love and partnership had been shattered, and I was seeing two examples of this happening in my family in the same year. It was much easier for me to take all that pain and to focus it on my grandparents’ relationship instead of my parents’.

I’m also the person in the family who will be like ‘wait a second, what’s going on here.’ All of the women in my family have this strong keep-it-moving kind of energy. After he died, they seemed to be accepting it and moving on. I guess I was [wondering] ‘okay… but how does that work when we just found out my grandfather had a completely secret life?’ I wanted to know, how are these women in my family dealing with these really difficult things? And how are they not resentful, like I was?

I think that I decided to make a film because that’s how I knew I could process this information. I needed to really sit with this huge event in our family, and I didn’t want it to be brushed off like it was normal, because it was traumatic. I don’t think people ask elderly people how they’re really doing, we assume that they’re okay because they’ve lived so much life already. I knew that nobody was asking my grandma that question, and I was right that she wanted to be asked because once I got her to open up she told me everything very honestly. I had to be sensitive to her experience, but I also needed answers, and she was more than willing.

“I spent a lot of time observing my grandmother and her routines. Ingrained values like hygiene and grooming are so culturally specific and so feminine. I was trying to capture her femininity, her identity, and to portray how these daily solitary rituals we practice show how we manage even the most difficult things in life.” – Aguirre

T: We follow your grandmother throughout the film as she does her regular routines – her hair care, making lunch, doing some sewing – and a little after the 5 minute mark you reveal the topic of the film when she mentions, “If I knew what I know now, I would have left Victor.” But it isn’t until the very end that we know what this revelation is, why did you decide to frame it that way?

G: In the opening shots I wanted to instill some eeriness and haunting energy. I played with music and some miscellaneous audio in the intro, so that the viewer knew not to expect a cutesy film about a sweet old lady. Her story is meant to raise questions about love, not answer them. What does love look like at the end of a lifetime? And if, after all that time, you discover deception and lies, what does that say about the love you may have once shared? And I also wondered, is it really true that she didn’t know? I feel like women always know, but that question remains unanswered for me.

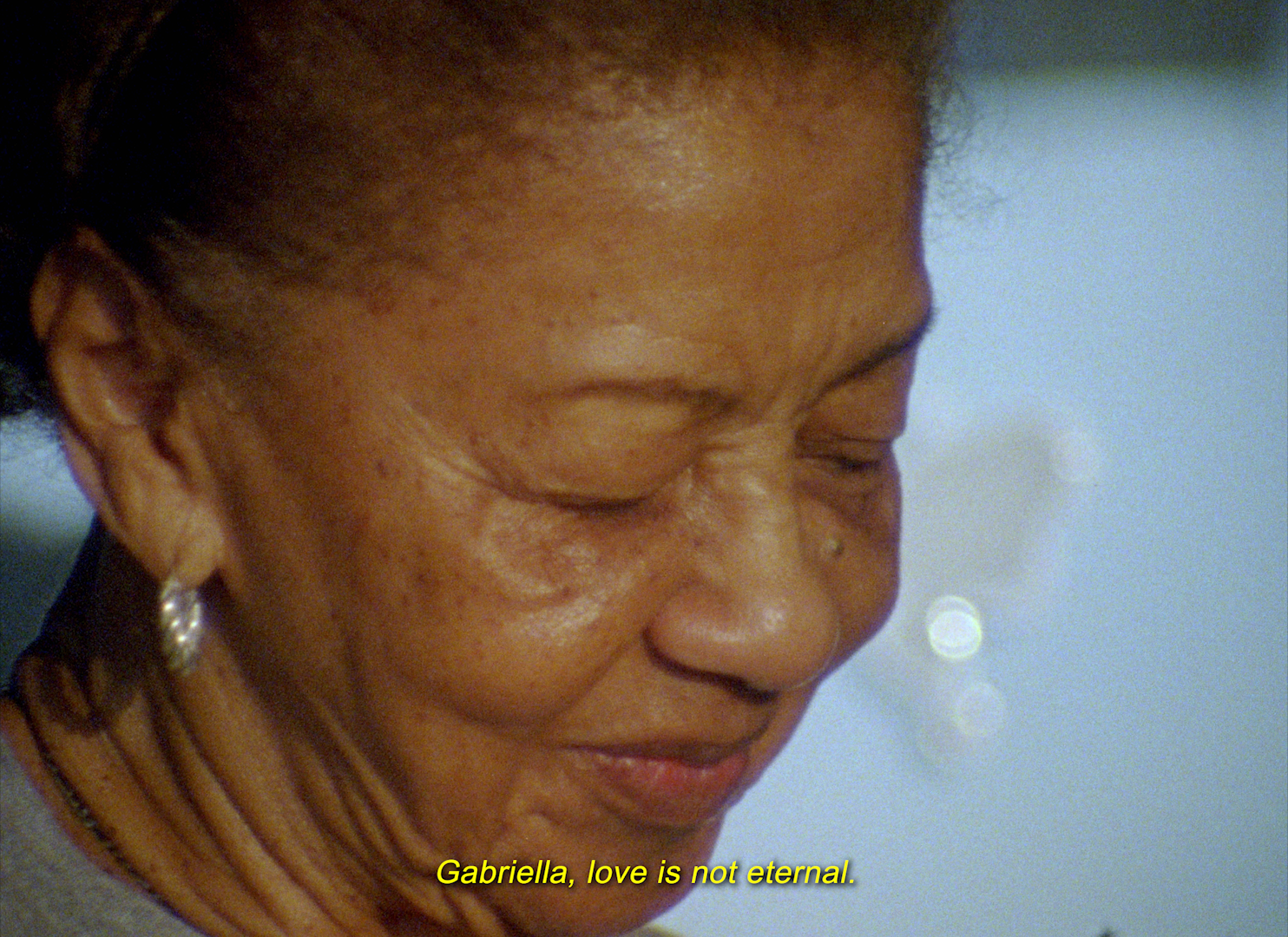

At the end she’s talking about how love is not eternal, and that if it doesn’t end, it changes. After talking to her so much during these interviews, I realized there is no “clean” way to close the story. She really is accepting it and moving on, and I think that at her age, that’s the only option. So many things in life are left open-ended, and you either choose to remain in that space, or you accept it and move on. For my grandmother, that’s just the way that she’s living now. As she says, it’s not “vale la pena” [it’s not worth it].

“My grandma is the costurera [seamstress] of the family. She worked as a bridal seamstress when she immigrated to the US, and she still alters all of our clothes. She is so active and at 87 her mind is still sharp, and I think that’s because she’s maintained these hobbies and skills throughout her life. I wanted to show how important that is to her.” – Aguirre

T: One of the questions I thought about as I was watching the film was, what does happily ever after look like? Especially after she talks about being a romantic and believing in fairytales and even though she says, ‘love is not eternal,’ it doesn’t really feel like she stopped believing in love. Do you think her view on love really changed?

G: I think that she recognizes that it looks different for every relationship, but also that despite this devastating discovery, in some ways she did [have a fairytale]. She had this lasting marriage for most of her life, and together they made a family, and they were all able to immigrate to the US when things were really difficult in Colombia. As a result we all have these beautiful lives, and my grandparents were able to spend his last moments together. In a lot of ways, that can be seen as the “fairy tale.” I guess what’s missing is this idea of true love. But through this, I learned she still does love my grandfather, but it’s not the kind of love we dream about as children, it’s pure devotion. She was devoted to him, and she took care of him. And even after these secrets were revealed to her, she was still by his side, and still his partner, and that just speaks to her values and her ideas of what the “fairy tale” is.

“Apart from all of the voice-over, in the edit I felt that the film needed something evocative and non-verbal, so I wrote this dream sequence and we shot it with her in New York. Although I focused the film on her healing instead of the dark details of the story, I wanted to insert eeriness and darkness into the film to contrast the footage from Colombia. It was also important to emphasize spirituality as her method of healing.” – Aguirre

T: At the halfway mark we see an incredible scene of your grandmother at a church, surrounded by sugar cane and walking towards an altar. The scene almost feels like you’re attending a funeral, and the viewer can interpret it both as possibly your grandfather’s funeral or even a funeral for an old version of your grandmother? Tell me more about the scene, what did you envision and what was the goal?

G: My original idea was to write this as a dream sequence, where my grandmother is facing these themes of betrayal and devotion in the context of religion. We shot this scene on 35mm film and actually lost a fair bit of it in processing due to a camera issue, so there are some key shots that got ruined and were unusable. I like that the scene is now more abstract and open to interpretation, though, and that it evokes essences of mortality and mourning. When I wrote this, I wanted to consider her age and the new phases of life that emerge from death, and that, for her, life isn’t over even though everything she thought she knew has changed. I can’t imagine what it would be like to discover that your life partner had a completely secret life. That’s why I made this film, to try to understand how she’s moving forward with her life now.

As far as the visual motifs, using real sugar cane was key. We filled this giant church with over four hundred sugar cane stalks that my production designer, Izzy Garcia, and I sourced from all over the city in one day. It’s a really important visual element because sugar cane is so central to Cali’s identity. When you land in Cali the air is sticky and so sweet that you can actually taste it. Sugar cane fields are everywhere, so I used the caña as a grounding motif in the film. We also have some shots of live ranas (frogs) in this scene which follows the Latin American nursery rhyme: “sana que sana colita de rana, si no sana hoy, sanara mañana.” In English, it means “heal, heal, little frog tail, if you don’t heal today, you will tomorrow.” I thought that perfectly encapsulated the message of the film, when something is broken, you will heal. I just wanted to know, how?

“We actually used live toads for this scene which was a fun surprise for everyone on set. They’re meant to directly represent my grandparents and the trauma and healing they both experienced in their lives. (No frogs were harmed). ” – Aguirre

T: There are a lot of child-like elements throughout the film, like your grandmother’s teasing as she talks about men looking at you or when she mentions why she keeps her hair done. The idea of fairy tales are also played with throughout, both explicitly as your grandmother discusses her own beliefs in them, and then symbolically with images of frogs which have often appeared in fairy tales themselves. At one point, we also hear a young child sing the Sana Que Sana Nursery rhyme. How did you see this child-like figure informing this story?

G: In retrospect, I can see that there’s a pretty clear inner-child motif throughout the story. It’s almost like this third-person, omniscient character [is] watching me ask my grandmother what her healing looks like, and offering the healing to both of us as we make this project together. [This figure is] sort of telling us that we’re both going to be okay. I think this is a story of duality; maintaining innocence and acceptance of reality, and that’s what I learned through this. My grandmother teases me about men checking me out, but then goes on to talk about romance inevitably dying. I think it all ties into the fact that nothing is black and white, and once you accept that, life, love, and loss are in the grays.

“Sana Que Sana” went on to screen at the San Francisco Latino Film Festival, Indie Memphis Film Festival, New York Shorts, and Aesthetica Film Festival. You can find more information about the film at Aguirre’s website. Keep an eye out for an online public release.

Film Credits: Directed by Gabriella Aguirre, produced by Brydie O’Connor and A Frame, cinematography by Gabriella Aguirre and Ben Elias, edited by Louisa Merino and Gabriella Aguirre, colored by Dylan Pailes-Friedman, art director Izzy Garcia, gaffed by Alexander Fischetti, score by Taul Katz, sound design and original composition by Jose Benjamin Escobar, featuring Sefora Gomez and the voices of Maria Teresa Garcia and Victor Gomez Jr, still photography by Nick Shaya.