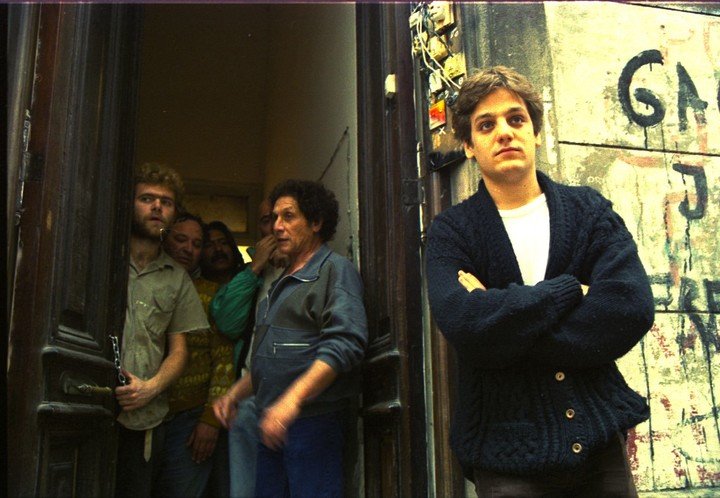

Earlier this year, the Argentine TV series “Okupas” was re-released on Netflix. Originally airing from October through December of 2000, right before Argentina descended into a dire economic crisis in 2001, “Okupas” follows Ricardo, a middle-class twenty-four-year old who has just dropped out of medical school. In the first episode of the series, Ricardo’s cousin asks him to live in her big, downtown Buenos Aires house in order to prevent squatters from taking it over.

While at first Ricardo agrees to this arrangement, the subsequent episodes show him integrating himself into Buenos Aires’s informal economy, befriending the people squatting in adjacent buildings, and eventually letting his new friends and acquaintances squat in his cousin’s building. The economic crisis isn’t at its peak, but things are already looking bleak for him and others his age. You can feel the weight of his future — or lack thereof — right away in the series, an anvil hanging overhead, ready to drop at any moment.

This is the genius of “Okupas:” it hints at what’s to come but none of its characters know for sure. At the time of its original airing on television, it was simply a dramatized depiction of what many people were living through as economic and living conditions deteriorated in Argentina. The allure of the show was the plotline, the intrigue of what would happen to this clean-cut young guy, dealing with squatters, drug-dealer friends, and down-and-out acquaintances.

Watching it now, twenty years later, knowing how the 2001 crisis crushed the hopes of millions of people and led many to leave the country and try their luck elsewhere (my family among them), the allure of “Okupas” is not found in what could potentially happen, but in the fact that we know exactly what will happen. We know something the characters don’t. The 2001 crisis left millions unemployed and wiped out the savings of hundreds of thousands when the currency depreciated. Many international companies that had set up shop in Argentina left, taking employment opportunities with them.

Okupas se estrena este martes, Día del Amigo, en Netflix pic.twitter.com/OwC4FLeF57

— La Izquierda Diario (@izquierdadiario) July 19, 2021

The decision by Ricardo and his friends to take their lives into their own hands, while a result of their immediate needs, seems sharply prescient in retrospect, and like a small-scale version of the neighborhood and workplace assemblies that would form in 2001 and 2002 as a result of the growing distrust in corporations, the government, and even organized labor. The series is not particularly well-acted, well-shot, or well-written, but it’s powerful in how it serves as a time capsule for a very specific moment in Argentina’s history pre-economic collapse.

Watching “Okupas” today lets us, for the duration of its eleven episodes, entertain for a moment that the story might have ended differently; not that the crisis wouldn’t have happened, but that maybe people could have organized themselves differently. The impulse to take matters into their own hands — to squat, to steal, to sell drugs — is one aimed at individual and short-term survival, as opposed to collective, long-term organization and actual political power. The structures set up by Ricardo and people like him — the neighborhood assemblies, the squat houses, the factories that were taken over by workers — served their immediate purpose: they helped people live through a dire crisis. Seen through the lens of a global pandemic and impending climate catastrophe, “Okupas,” in addition to a time capsule, is also a cautionary tale.

We might be tempted to similarly organize ourselves to meet our immediate needs and we should. But we should also think bigger and more long-term. The world-historic crisis through which we’re living may not look exactly like the world of “Okupas,” but it is similarly a result of a world in which many work day-in and day-out to line the pockets of a few. Ricardo and El Pollo take their individual fates into their own hands; we should take our collective fate into ours.