“For us, stories are living beings,” writes Nemonte Nenquimo in the introduction of her memoir, We Will Be Jaguars: A Memoir of My People, co-written with her husband, and fellow activist Mitch Anderson, “A story dies when no one tells it.”

“This book centers my thoughts: how I look at evangelicals, how I look at white people,” Nenquimo shares with me over a video call while on a family vacation with her in-laws in Petaluma, California, a drawing of a densely populated jungle hanging behind the white couch Nemonte sits in with her husband and children. We Will Be Jaguars, released in the U.S. on September 17, is a testimony of her upbringing. “I asked my dad, ‘How about sharing our collective struggle? Our memory. Making the world understand is necessary,” she recalls. “We began remembering with my dad, my mom, my brothers, aunts. Many times, evangelicals, and anthropologists have given their perspectives. But no one has written, our memory, the true history.”

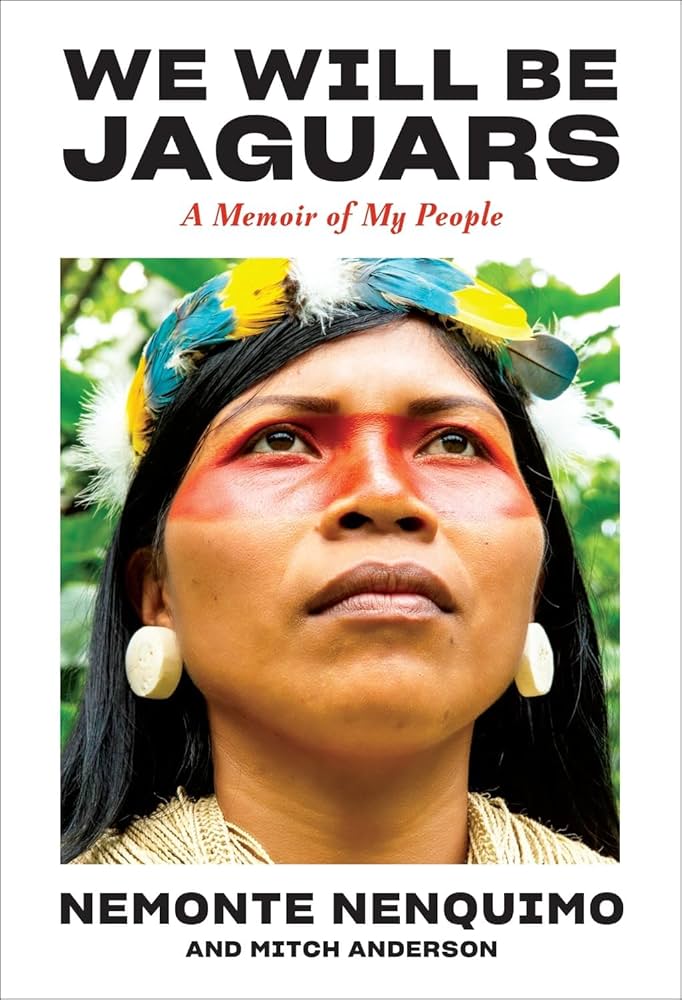

Nemonte Nenquimo is among the world’s most recognized Indigenous climate activists. On April 23, 2019, she was the lead plaintiff in a landmark suit against the Ecuadorian government’s planned auction of Waorani land to oil companies. After a three-day trial, the verdict stated that the government had conducted a faulty consultation process with the community prior to putting their territory up for sale. Under the leadership of Nenquimo, the Waorani people asserted their right for self-determination, culminating in the protection of half a million acres of their rainforest. On April 26, hundreds of Waorani flocked to Puyo, Ecuador, streaks of achiote red pigments adorning their eyes and declared them Waorani. They had won over a system that long deemed them voiceless.

Photographed by Thalía Gochez.

Nenquimo was born in 1985 deep in the Ecuadorian Amazon as a member of the Waorani tribe. It was among the last tribes to be contacted by American missionaries in the 1950s and known for resisting previous contact attempts. Experiences and life stories like Nenquimo’s have been told by anthropologists and other outsiders looking in for far too long. Nenquimo achieves a monumental feat in reversing colonial narratives, using the written word to center generations of Waorani cosmovision. It joins the company of The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, Davi Kopenawa Yanomami’s 2010 memoir documenting his life story as a shaman and Yanomami spokesperson and the cosmo-ecological thought of the Yanomami in the Brazilian Amazon.

The book serves as both a recollection of a people and a coming-of-age tale covering nearly three decades of her community, from the early 1990s through 2019, from the first time Nemonte sees a plane land near the Curaray River to the ever-rising tensions between settler evangelicals and nearby oil companies in the last decade. Youth and elders can either accept missionary hymns, Western clothing, and work for the oil companies or find forms of fighting back. Some flee their land while others accept employment, but in the end, they must all come together in response to the oil companies’ poisoning of their water supply.

Photographed by Thalía Gochez.

For Nemonte, the process of remembering her adolescence meant confronting deeply painful memories she had long repressed. At 14, Nenquimo left Nemompare for the first time to study with an evangelical missionary group in Quito. She writes from a place of empowerment with women in mind as she recounts stories of sexual abuse and her journey towards unlearning prejudiced viewpoints held by the so-called “civilized” world. Naming the harm became a step on the journey to healing and transformation. “It was a difficult process of remembering,” Nemonte says. “I kept so many things hidden for so long”

By far, the hardest memories to unearth pertained to her late brother Victor or Mengatowe. “It was very emotional to talk about him and then listen to the stories. I went to the waterfall crying and asking Victor to join me and help me to write this book so that everyone can see mother nature,” explains Nenquimo.

With Victor’s blessing, Nenquimo expresses an urgent message: “How can I make the world respect Waorani, respect mother nature? Many elders say, ‘outsiders know more about destruction than the jungle.’ We need to remind cityfolk that they are also connected to the earth, connected to the air, connected to the water.”

We Will Be Jaguars: A Memoir of My People by Nemonte Nenquimo and Mitch Anderson

We Will Be Jaguars arose from years of early-morning conversations with Anderson. A few days before the birth of their son Sol, Nemonte began sharing stories with her husband. Guided by generations of oral tradition, Nemonte would recite while Mitch would transcribe. Over the next two years, the two collected enough stories from Nemonte, friends, and loved ones to begin weaving a tapestry of the Waorani people. She insists that Mitch is not a translator, “My husband lives in our territory. He is one of the activists that works and fights with us. We’ve learned from him, just like he has learned from us.” Mitch is the founder and executive director of Amazon Frontlines and has long worked with Indigenous nations throughout the Amazon to defend their rights to land, life and cultural survival. During our interview, Mitch distracts their two kids Sol and Daime while Nemonte tells me her recent dreams. It’s a small glimpse into their partnership.

As its title suggests, We Will Be Jaguars asserts the future without erasing the past. It is a promise towards reclaiming and amplifying Waorani knowledge—a self-documented celebration of the tribe’s rich history and culture. Importantly, as so many of us watch, all but frozen with fear, as our world seems to be inevitably consumed by rising tides, burning forests, and deepening inequalities, We Will Be Jaguars is a portrait of the modern revolutionary activism undertaken by Nemonte and her husband, peers, and ancestors. Our task is to listen with humility, then ask ourselves: What action can we take now?