As a child growing up in a large Mexican-American family, I heard countless tales of new beginnings, adventures, reunions, losses, and joys from my older relatives. The context for nearly every story was the border town of Brownsville – Texas’s southernmost city – where my parents and grandparents were born and raised, and where my extended family continues to live today. One story, in particular, always tugged at me – for it seemed incomplete, if not embellished.

For eight generations, my relatives told a tale stemming from a property transfer that happened almost one hundred and seventy five years ago. Family lore holds that the U.S. government robbed an ancestor, Miguel Salinas of a huge tract of prime land on Brownsville’s Rio Grande River. The purportedly stolen land became the site for Fort Brown, the military stronghold from which the United States successfully won the Mexican-American War in 1848.

While I always assumed that there was some foundation in fact, I also assumed that the law would never have allowed a truly uncompensated dispossession. But when a distant relative asked for my help, I started on a path to some surprising discoveries.

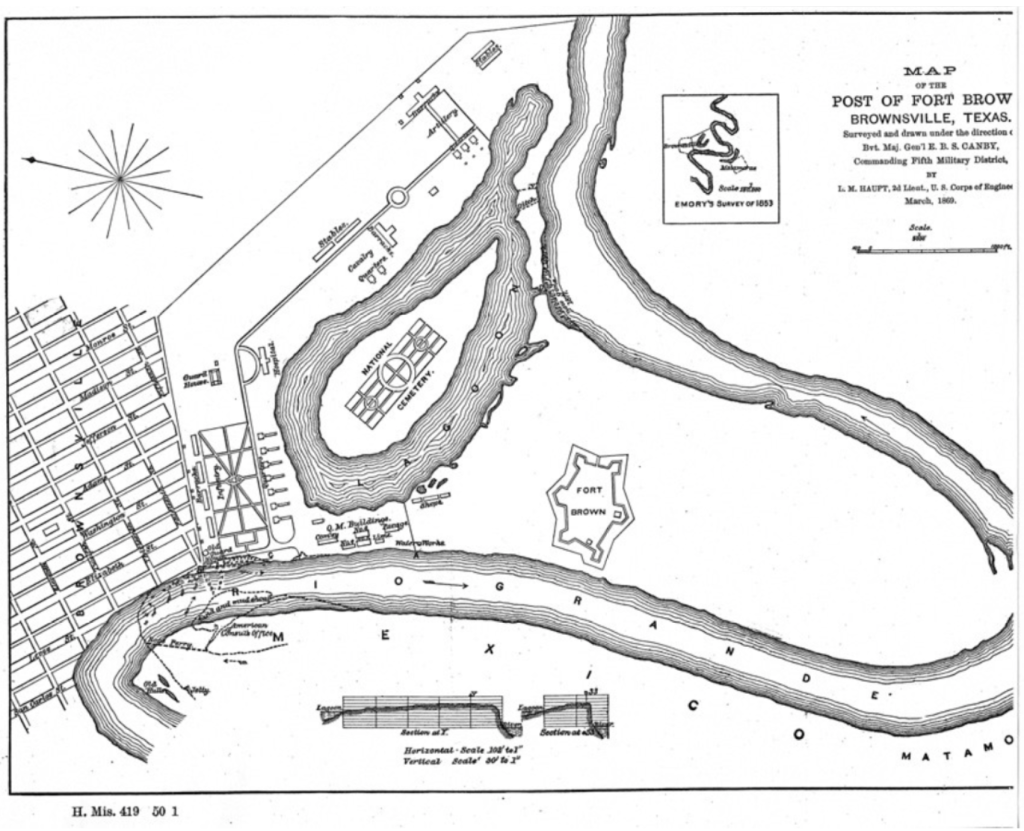

Fort Brown Maps, UTRGV Digital Library, The University of Texas – Rio Grande Valley.

“I Believe in Miracles”

“I believe in miracles, and just maybe you are the one to do something about this,” said the cover note accompanying a thick package sent two and a half years ago by my mom’s cousin, Bertie Lucio Caballero. Bertie, the genealogist of our family, had spent nearly four decades piecing together historical documents, clippings from the Brownsville Herald, and various family trees. Bertie told me she believed that as a law professor, I could help right this wrong. She ended her letter: “Maybe, Miguel Salinas will rest in peace, when we, his descendants, receive the monies we rightfully deserve.”

After thinking about her letter, I decided I had an obligation to investigate. My professional path had readied me for the task: as a professor of property law, an advocate for land use and zoning reforms, and a historic preservationist committed to “telling the full story” about the past, with all of its messiness and contradictions. As a member of the board of the national nonprofit Latinos in Heritage Conservation, I’d become all too familiar with the dearth of knowledge about Latino contributions to American history, and passionate about correcting it. If my family had a place in this chapter of American history, and if I could restore them to the story, then I had a duty to do so. I promised Bertie that I would look into it.

My research would involve reviewing the family tree, deciphering court cases well over a century old, interviewing family members, and reading historical analyses. I discovered the unexpected: while my own close relatives, Bertie included, no longer had any real claim to the land, Miguel Salinas was indeed robbed – and the law turned a blind eye.

This finding reinforced a heavy truth: that property law, like other areas of law, often rewards the most privileged, with profound ramifications for generations.

Miguel’s Land

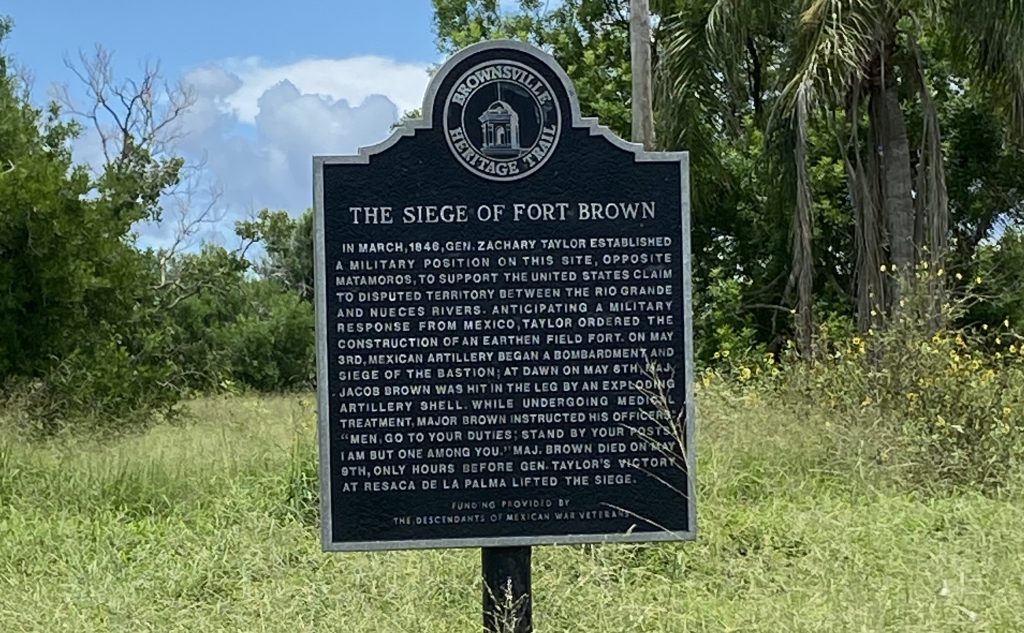

Last summer, I made a pilgrimage to Salinas’s land. Any traces of my family’s claim to the site had long been erased. I did find a marker overgrown with vegetation announcing the “Original Fort Brown Site” and extolling Jacob Brown as the “gallant commander who nobly fell in its defense.”

Yet the story of this land begins much earlier. In 1519, the Spanish “discovered” and started exploring the Rio Grande Valley, which had been occupied by nomadic Coahuiltecan tribes for thousands of years. In 1781, when the Spanish began settling there, the King bestowed a land grant to José Salvador de la Garza, which included an area larger than all five boroughs of New York City, located directly on the Rio Grande River. By 1826, the land had been subdivided, and twenty-three acres were leased to Salinas, who purchased it in 1835.

Salinas was a good manager and rancher. He maintained a healthy herd of cattle and grew diverse and abundant crops of cotton, corn, sugar, cane, and beans. He built twelve brick buildings, erected a windmill, and enclosed his land with a sturdy fence. But as he tended to his ranch, war loomed.

Author Sara C. Bronin at the US-Mexico Border Fence.

Dispossession

In 1846, just eleven years after Salinas purchased his property, General (and future President) Zachary Taylor marched into the Rio Grande Valley. President James Polk – champion of the Manifest Destiny theory – had sent him to battle Mexico over the location of the southern border of Texas. Taylor viewed Salinas’s land, situated on a river bend, as a prime defensive location. His troops forced Salinas to sign a lease in English (a language he did not speak) which relinquished his land to the federal government.

I wonder what went through his mind as he gathered his family and left the life he had built and the land that sustained him for twenty years. I wonder how many hours General Taylor’s troops gave him to vacate. I wonder what he left behind.

The Salinas property became a critical location for American troops. Just three weeks after General Taylor’s seizure, the land saw its first battle. The Mexicans got the upper hand, killing two American soldiers, including Jacob Brown, after whom the fort was eventually named. A second battle, Resaca de la Palma, resulted in a Mexican defeat — and precipitated a Congressional declaration of war.

Not a Dime

Salinas, as the owner when Taylor seized the property in the name of the U.S. government, was entitled to payment. But federal authorities refused to give him a dime. Hoping someone else could do better, Salinas assigned his son José Antonio to carry on the family claim. (That assignment severed the interest of my branch of the family, as we are descended from another son.)

José Antonio and his successors had to fight not only the federal government for compensation, but also others who began making competing claims to be the wronged owners. These legal battles lasted for nearly sixty years. Dozens of judicial decisions, filings, Texas Attorney General opinions, and Congressional committee reports lay out the sordid details. These documents reveal the shady involvement of a White, wealthy, Connecticut-born entrepreneur, Charles Stillman, and his family and business associates. Using their vast wealth and deep political connections, the Stillmans became the beneficiaries of the handsome compensation the federal government eventually paid. Despite trips to the Fifth Circuit and even the Supreme Court of the United States, the Salinas heirs received nothing.

Plaque at the site of Fort Brown. Photo courtesy of the author.

Generational Reverberations

When General Taylor marched on his property, Salinas was a wealthy man. But any hope of recovering that fortune vanished when influential English speakers continually triumphed in a legal system that prioritized their interests.

The effects of the dispossession lasted generations. Salinas’s great-grandchild, my great-grandmother, lived her ninety-six years in relative poverty a few blocks away from Fort Brown. Her adult life was shadowed by the Salinas land theft. Her sense of loss was so much a part of her identity that her obituary included a reference to Miguel Salinas and the stolen land. At some point, she even traveled to Mexico City with a relative to speak with officials about the claim. We have no family letters or journals to fill in the blanks on this trip, or to bring personal details to the public records documenting the land dispossession.

Later generations have moved on, even though the dispossession deeply affected their social and economic standing. My grandparents were the first generation to speak English, and my parents were the first generation to finish college. My sisters and I were the first to earn graduate degrees in law, business, and medicine. On the one hand, our trajectories testify to the opportunities provided by our country. On the other hand, I can’t help but wonder what contributions those intervening seven generations might have made if they had been able to build upon the foundation that Miguel Salinas worked so hard to lay.

In recent years, there has been much talk of reparations being used to right the wrongs of the nineteenth century. Some Rio Grande Valley residents have asked for reparations for land grabs like my family’s. Only one family — the Ballís — have successfully reclaimed their land, a story chronicled by cultural anthropologist Cecilia Ballí in Texas Monthly magazine. Others, recognizing the reality that such requests are usually fruitless, have given up.

My research confirmed the truth of my family’s story and gave Bertie her long-awaited answer, though not the monetary compensation for which she had long hoped. But Salinas’ story should be recognized as a piece of the Fort Brown site’s history. The contributions and concessions of families like ours are a part of the American story. Preserving these stories gives places richer meanings. And perhaps telling these stories can keep us from making the same mistakes again.

Sara Bronin is a Mexican-American, seventh-generation Texan, architect, attorney, Chair of the U.S. Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, and professor (on leave) at Cornell University. A longer version of this story with corresponding citations appeared in the Latino Book Review.