“There’s nothing wrong in playing dress-up. We have men who have waited, we have women who have waited until they’ve been almost dead to think about dressing up. I did not have that much time, I dressed.”

–José Sarria, 1997

The biography of political activist and legendary drag artist José Julio Sarria, Absolute Empress I de San Francisco, opens with his two family trees: “biological” and “adopted.” A descendant of large, wealthy families with roots in Spain and Colombia, the life of José Sarria, founder of San Francisco’s International Imperial Court System, was deeply rooted in an awareness of the power of pedigree.

Born on December 13, 1922, Sarria explained his lifelong fascination with royalty as a product of his youth in the interwar period, a time “of kingdoms” when “there was still a lot of places where there were kings and queens that you read about in the paper.” As a child, Sarria’s favorite role was, of course, the queen.

“We would build carriages and sedan chairs,” he described of his childhood play. “I rode, they carried, they pulled! I was the boss.”

Nearly 50 years later, Sarria would become the “Dowager Empress to a lengthening line of successors,” according to his biographer, “as well as dukes, duchesses, czarinas, and assorted Court dignitaries.” Through the Imperial Court, Sarria oversaw a sprawling volunteer fundraising organization that, in its early years, primarily organized charity drag shows and other events to raise funds for the local queer community.

The Imperial Court’s hierarchy developed out of annual coronation and investiture fundraisers in which local chapters of the Imperial Court elected a new leader. In turn, the newly crowned monarch presented court titles to officers who would serve the community under their reign. As the inaugural, self-appointed Empress, Sarria set the Imperial Court’s tone of campy yet elegant pageantry.

But Sarria’s activism began several years before his coronation, emerging in the Bay Area’s queer bar circuit that included The Pearl in Oakland and the Black Cat Café in San Francisco.

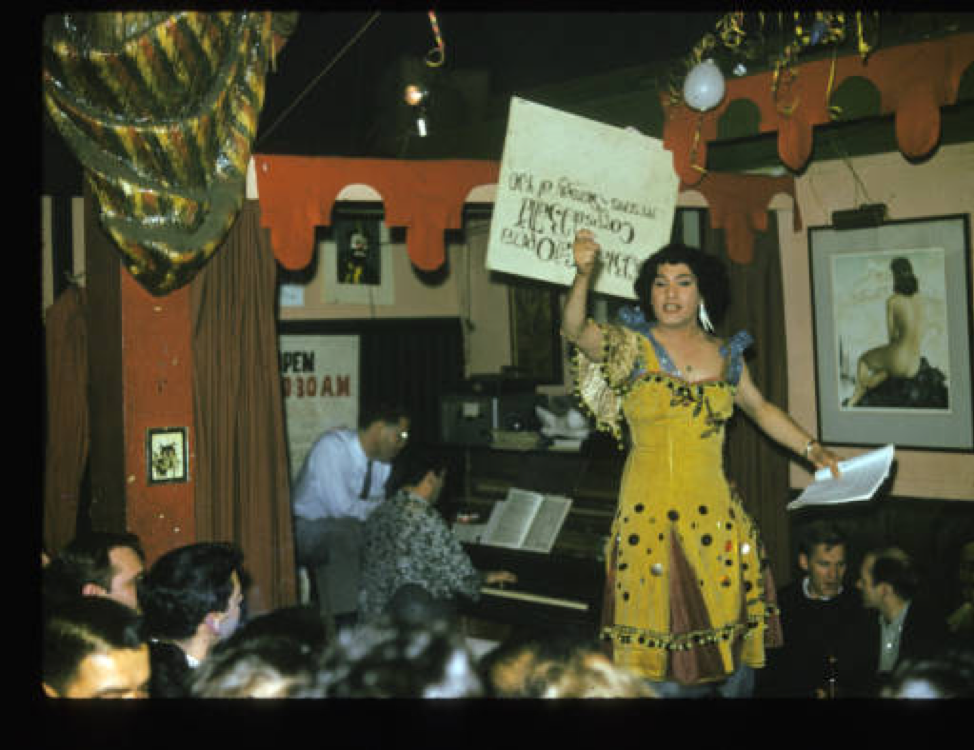

Honorably discharged from the military during World War II, Sarria quickly gained recognition for his singing talent while working as a cocktail waiter at the Black Cat, where he was hired to perform nightly parodic operas as “The Nightingale of Montgomery Street.” Celebrated for his performances of arias adapted from Carmen, which Sarria reworked to tell a melodramatic tale of cruising and evading the local vice squad in present-day San Francisco, and his ritual of leading patrons in a rendition of “God Save Us Nelly Queens” at last call, Sarria developed a loyal following. Harvey Milk’s biographer recalled that Sarria sometimes brought the Black Cat crowd into the streets to perform for men who had been arrested in police raids earlier that night.

José Sarria at the Black Cat Bar; Source: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15799coll4/id/5458/rec/28

Police raids of gay and lesbian bars were a routine, and often violent, occurrence in the lives of queer people living in the United States in the 1950s and ‘60s. Afterwards, arrested patrons often saw their names, addresses and workplaces published in local papers.

The 1969 Stonewall uprising, a major catalyst for the U.S. gay liberation movement, began when patrons at the Greenwich Village bar fought back against a routine police raid and set off a riot.

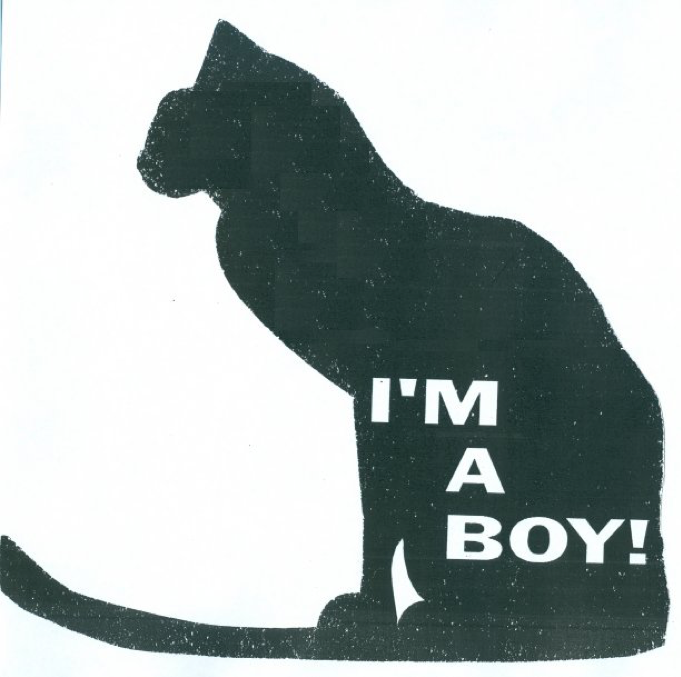

Drag queens and trans patrons in San Francisco were particularly vulnerable during raids, as they were often arrested under local ordinances that criminalized cross-dressing “with an intent to deceive.” The 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria riot in San Francisco has been credited as the start of organized trans activism, when trans women and drag queens resisted arrests specifically targeting those who police perceived as men dressed as women.

In the late 1950s, Sarria consulted an attorney and began distributing black cat-shaped tags to fellow drag queens that read “I’M A BOY” to counter police claims of deception. He also advised arrested patrons not to plead guilty, as was routine, but instead to demand time-consuming jury trials that forced police and prosecutors to meet a fairer standard of evidence, thus overloading court dockets and discouraging discriminatory mass arrests.

Source: https://www.queermusicheritage.com/nov2012s.html

In 1961, Sarria became the first openly gay candidate for public office in the United States when he ran for a seat on the San Francisco Board of Directors. Out of 34 candidates, Sarria earned nearly 6,000 votes and finished ninth. And though he did not secure a seat on the board, his run proved possible a politically significant gay voting bloc in city politics, laying the groundwork for the future election of openly gay leadership in San Francisco, including that of Harvey Milk. With Sarria’s endorsement, Milk won a seat as city supervisor in 1977 on the same board Sarria had campaigned for 16 years earlier.

Sarria at a protest at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco; Source: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15799coll4/id/1933/rec/39

Following his unsuccessful bid for local office, Sarria helped form the first-ever gay business association in the United States, the Tavern Guild of San Francisco (TGSF), founded to protect gay bars from the constant police raids that threatened both their patrons and liquor licenses. The TGSF established a phone network that tracked police and warned Guild bars of potential raids while raising money for bail funds and legal fees for patrons and employees arrested at TGSF bars.

In 1963, Sarria founded another homophile organization, the Society for Individual Rights, dedicated to grassroots organizing efforts including voter registration and the publication and distribution of “Pocket Lawyers”: pamphlet guides containing practical legal advice for queer community members facing arrest or police harassment.

In 1965, the TGSF honored Sarria at the third annual Beaux Arts Ball, San Francisco’s oldest large public drag ball, crowning him queen of the event. Noting that he had already long been a queen, Sarria proclaimed instead that he accepted the title of “Her Lady, Empress of San Francisco, José I.” Sarria also called himself “The Widow Norton,” a tongue-in-cheek reference to San Francisco’s Joshua Abraham Norton, an eccentric 19th-century radical who had once declared himself “Emperor of the United States” and “Protector of Mexico.” Bedecked in a flowing black gown and veil, Sarria staged annual pilgrimages to Norton’s grave in nearby Colma, California from 1975 to 2005.

In 2007, Sarria abdicated his throne as Empress to longtime Latino LGBTQ activist Nicole Murray-Ramirez, marking the end of a 42-year reign of pioneering political activism and unforgettable queer pageantry. By the time of his passing in 2013, “Mama José” Sarria was widely recognized for his charitable work and fierce resistance to anti-LGBTQ discrimination, receiving numerous lifetime achievement awards at Pride Celebrations across the United States and appearing alongside legendary drag performers in the 1995 film To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar.

Given a funeral befitting an Empress (one attended by about 1,000 mourners including state elected officials and Imperial Court leadership), Sarria was buried with full military honors in Woodlawn Memorial Park, a place he had frequented during his life. The Empress was laid to rest in a plot at the foot of former “Emperor of the United States” Joshua Norton, the only other Bay Area monarch whose royal title had ever matched Sarria’s own.