With “la voz áspera de la ternura,” there’s no mistaking the iconic sound of Chavela Vargas.

Born Isabel Vargas Lizano in San Joaquín de Flores, Costa Rica, in 1919, Vargas got her start when she left her native country as a teenager to pursue a career in Mexico’s growing entertainment industry. After over a decade spent working as a street performer in Mexico City, Vargas slowly built her success in music, performing boleros, rancheras, and corridos as she partied hard at nightclubs across the city.

From the start, Vargas defied the gendered expectations of her era and the male-dominated ranchero music industry, dressing in men’s clothes and refusing to change the pronouns in the love songs she performed, such as “La Llorona” and “Piensa en mi,” which were written by men. Vargas drank heavily and smoked cigars, and was known for both her iconic red poncho and the gun that she often carried with her. In a 1991 interview, Vargas claimed that at the height of her fame she partied and shared beds with some of the biggest female stars of Mexico and the United States, including Ava Gardner and Frida Kahlo.

Vargas would later recount the memory of first meeting Kahlo in her autobiography:

Me quedé impresionada cuando vi que bajaban por la escalera de la casa, a la señora en una camilla y vestida de tehuana, los mariachis tocando y todos bebiendo tequila, una pachanga de tequila. Frida me invitó a quedarme a dormir, pues yo vivía lejos de Coyoacán. Después me fui quedando. ‘Quédate niña, me dijo, estás muy sola y no sabes nada de la vida, quédate en mi casa’, me dijo. Y yo me quedé. Ella pintaba y yo cantaba.’

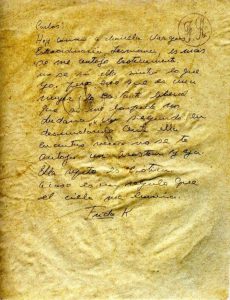

In a letter to poet Carlos Pellicer, Kahlo described her own feelings that evening:

Carlos:

Hoy conocí a Chavela Vargas. Extraordinaria, lesbiana, es más se me antojó eróticamente. No sé si ella sintió lo que yo pero creo que es una mujer lo bastante liberal que si me lo pide no dudaría un segundo en desnudarme ante ella. Cuántas veces no se te antoja un acostón y ya. Ella repito es erótica. ¿Acaso es un regalo que el cielo me envía?

Frida K.

Letter from Frida Kahlo to Carlos Pellicer; Source: Revista Central

One of Vargas’ most famous songs is “Macorina,” adapted from Spanish poet Alfonso Camín’s poem of the same name. The song described the beauty of Maria Calvo Nodarse, a Cuban prostitute of Afro-Chinese descent better known as La Macorina, who moved through Havana’s wealthiest social circles, wore her hair short, and quickly amassed a fortune in furs, jewelry, mansions, and expensive cars.

Vargas claimed that the inspiration for “Macorina” came to her after meeting Nodarse herself in Havana. In the documentary El amor Amargo de Chavela, Vargas described her first impression of the Afro-Cuban beauty: “Era una mujer guapísima. Negra mezclada de china. La vi y me quedé muda.”

Marvette Perez, curator of Latin-American Culture and Music for the Smithsonian Museum of American History, explained to NPR Music in 2010 how revolutionary Vargas’ performance of “Macorina” truly was for 1960s Mexico:

“I don’t think there could be a more queer song for a woman to sing. The song says, ‘Ponme la mano aqui, Macorina.’ Put your hand right here, Macorina. And whenever she sang the song, she put such sexuality, desire, and kind of sensuality into it that you knew why she was singing, why she was singing and to who she was singing it. She was singing it to a woman.”

Vargas’ singing style was similarly revolutionary for her time. Eschewing the accompaniment of mariachi, Vargas performed ranchera music solo, accompanied only by her own guitar. She sang slowly, stretching out the lyrics so there was no mistaking their meaning.

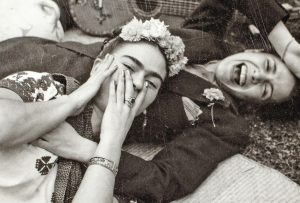

Frida Khalo and Chavela Vargas, Source: Revista Central

Vargas’ fame continued to grow during the 1960s. She released her first album, Noche de Bohemia, in 1961, and began touring internationally in Spain, France, and the United States.

By the late 1970s, though, Vargas’ heavy drinking and smoking began to take a heavier toll on her body, particularly her throat. And by the end of the decade, as Vargas drifted deeper into alcoholism, she was no longer performing at all. Vargas would later describe these years of her life in her autobiography as “hell,” as she struggled deeply with alcohol addiction until she was taken in by an impoverished family and nursed back to health and sobriety.

Vargas eventually made her return in 1991. She reemerged into the public eye on the same stages where she had gotten her start: nightclubs in Mexico City and Spain. As she regained her international fame through the 1990s, Vargas also developed a close friendship with Argentinian filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, who began to feature Vargas and her music in several of his films throughout the decade, beginning with Kika in 1993. The silver screen was not unfamiliar to Vargas, as she had previously made an appearance in the 1966 Mexican film, La Soldadera. With Almodóvar’s support, Vargas made her Carnegie Hall debut in 2003.

Although she made no secret of her sexuality throughout her career, Vargas came out as a lesbian in her 2002 autobiography Y si quieres saber de mi pasado. That same year, Vargas also appeared in the 2002 Frida Kahlo biopic, in which she performed “La Llorona.”

Vargas continued to perform up until her death in 2012, at age 91. Her last words: “Me voy con México en mi corazón.”