Chef Mateo Herrera describes himself as shy and soft-spoken. The El Paso, Texas-based Indigenous chef therefore surprised himself and others when he took to his Instagram stories in September to call out Sotol Raramuri, a Ciudad Juarez-based sotol brand, for their use of Native American and Indigenous Mexican imagery in their social media advertising. One of their ads is a sepia-toned photograph of a young woman. Yellow, red, and blue paint has been overlaid on the image: a yellow circle with red streaks implies the sun rising behind her head and her face has been painted with red and blue markings. Part of the caption on the image reads: “Sagrado Espíritu, sagrada tierra”—Sacred Spirit, sacred earth. A series of hashtags follow, including #desertspirit #corazonraramuri #piesligeros. On his stories, Herrara shared the image and said, “This is an ad for Sotol…When I see this, I see…Cultural Appropriation. Oppression. Ignorance. Brain washing. And the Perversion of ALL Indigenous People!!!”

Sotol is an alcoholic beverage, or spirit, distilled from the sotol plant. It is drunk primarily in the Northern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora and is often called a “native” beverage of the area. However, Sotol—like tequila and mezcal, both distilled from the agave plant—is not a native drink, even if it was invented in Mexico. Like tequila and mezcal, sotol was created using a mode of distillation that was brought to the Americas by Spanish colonizers. While new anthropological evidence might suggest that pre-Hispanic Indigenous people may have had their own distillation methods to produce mezcal, the alcoholic beverages that we know today as tequila and mezcal are a product of colonial imperatives to create a Mexican identity that blended Mexico’s “Indigenous past” with European “civilization.”

Sotol Raramuri is not the first or only brand to mistakenly call these Mexican spirits native or use Indigenous imagery and culture to sell their products. There is a long history of Native appropriation in Mexican cultural productions, including alcohol production, which scholars have shown is closely tied to the construction of Mexican identity. While tequila, mezcal, and sotol are advertised and sold as part of a mythic Indigenous Mexican spiritual practice, actual Indigenous drinks like pulque, tepache, and tesgüino are lesser-known and not inherently associated with lo Mexicano.

For Indigenous chefs and food sovereignty activists like Herrera, ads like those of Sotol Raramuri are a stark reminder of colonialism and the material consequences of appropriation and marginalization. Non-Indigenous brands profit off the images and cultural symbols of Indigenous people while, in Mexico, Indigenous and Indigenous-descended groups serve as the primary labor force to produce these spirits. Indigenous foodways are threatened by corporate agribusiness and international free trade agreements while their communities struggle with food insecurity and other food-based illnesses and health conditions caused by structural disenfranchisement.

The association of sotol, tequila, and mezcal with Indigenous identity and imagery is a form of cultural appropriation that hides a long-jagged history of colonization and Indigenous struggle that continues to this day.

Pre-colonial Drink

Indigenous people in North and South America have been making and drinking fermented alcoholic beverages for thousands of years. Geographer Henry J. Bruman’s book “Alcohol in Ancient Mexico” describes many Mexican pre-colonial beverages distilled from cactus, tunas aka cactus fruit, cornstalks, mesquite pods, maize, agave, honey, and tree bark. Perhaps the most well-known of these drinks is pulque (octli poliuhuqui in Náhuatl), made from the agave plant. Pulque is lightly fermented and today is often flavored with fruit such as mango or pineapple. In pre-colonial Mexico, it was considered a sacred mixture, drank primarily by the elderly, nursing mothers, and the ruling classes during festivals, celebrations, and ceremonies.

During the colonial era (1521-1821), food and drink played an important role in the maintenance of Spanish colonial race and class hierarchies. According to sociologist Marie Sarita Gaytán, Spanish colonists saw pulque and other Indigenous ingredients as inferior and offensive, so they imported wine, olive oil, and other European food and drink for consumption. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, non-elite colonists experimented with agave distillation, creating early versions of mezcal, or vino de mezcal, and drinks made from sugar cane and coconut palm.

In Gaytán’s book, “¡Tequila! Distilling The Spirit of Mexico,” she argues that pulque was seen as the epitome of Indigeneity. The consumption of pulque was understood as an inherently aberrant Native trait and justification for the Spanish belief in their own superiority. Not only did Spanish colonists find pulque “barbaric,” as they found most Indigenous practices, they were also threatened by the social role that pulque played during community celebrations that were seen as potential sites of rebellion. Some Spanish authorities even attributed Indigenous insurrections to pulque, rather than colonial disenfranchisement, which led to increased attempts to control pulque sales and to limit the expansion of pulquerias in Mexico City (many of which were run by lower-class Spanish or mestiza women.

The Mexican painter José Agustín Arrieta famously depicted colonial scenes in pulquerías, such as in the painting “Interior de una pulquería” from the 19th century.

The Introduction of Distillation

By the end of the 18th century, the Spanish government went from trying to regulate agave cultivation to imposing taxes on pulque sales and investing in the cultivation of agave to produce mezcal. In Western Mexico, Indigenous populations were decimated by violent colonizing campaigns. The survivors were forced into the colonial hacienda system. Jalisco became an important area of agricultural production and trade, particularly of agave, tobacco, and mezcal, which was created through the formal introduction of Spanish alcohol distillation methods by Pedro de Tagle, Marquis of Altamira and Knight of the Order of Calatrava, often referred to as the “father of tequila.”

According to Gaytán, while pulque was associated with the chaos of daily life in Mexico City (which was more racially mixed) during the colonial period, mezcal represented the stability of hacienda life (which was racially segregated to control the Indigenous and enslaved African hacienda labor forces). Thus, mezcal came to represent European superiority both in its association with Western distillation methods and in its reflection of dominance over Indigenous populations in Western Mexico.

In the early 1800s, mezcal production and consumption increased as did beer consumption, which was brewed by European brewers in northern Mexico. In the lead up to Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, Mexican elites began to fashion an independent cultural identity for the nation. They began to construct ideas of lo Mexicano and to attach them to certain foods and drinks. Mezcal and later tequila were deemed national beverages, while pulque, too closely related with Indigenous people and practices, continued to be seen as inferior and degenerate. The production and sales of mezcal and tequila took off with the construction of the Mexican railroad. As a lightly fermented drink, pulque could not withstand the journey across the country or to the United States, which prevented it from being exported internationally as well. Thus, mezcal and tequila traversed the nation and made their way to the United States, becoming popular drinks and signifiers of Mexican identity, while pulque remained a local beverage closely associated with the lower classes and Indigenous food practices.

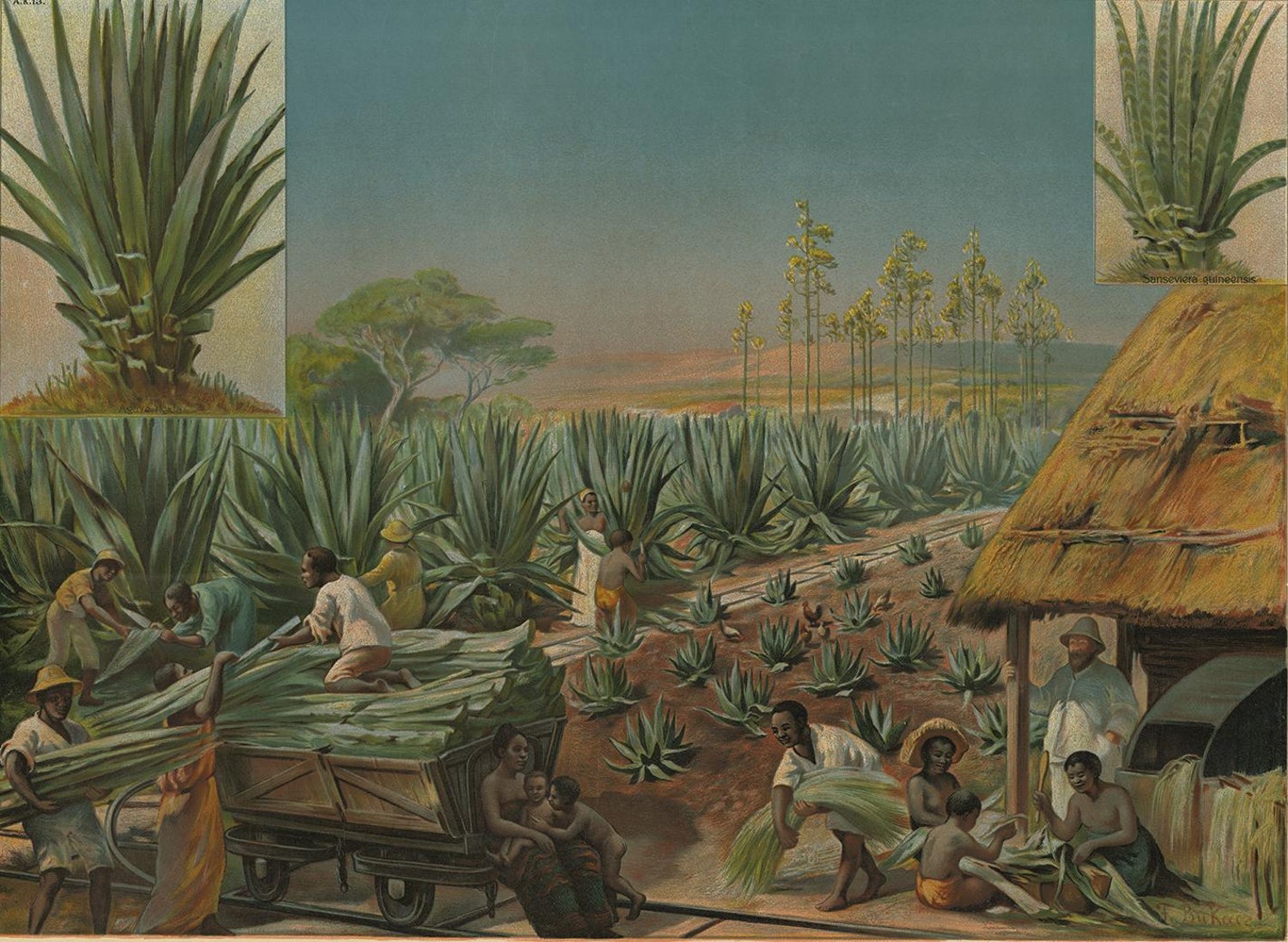

Antique Print, Schoolplate of a Sisal Agave Production Field by F.E. Wachsmuth.

Appropriation & Indigenous Afterlives

The early 20th century in Mexico saw major social, political, and economic upheaval and anxiety due to the European-influenced administration of Porfirio Diaz. Diaz called for modernization and economic expansion, working primarily to increase the wealth of the Mexican upper classes. Politicians were eager to begin constructing a modernized Mexican identity based on eugenicist models of race science that deemed Indigenous groups obstacles to modernization and mestizos, people of mixed Spanish and Indigenous heritage, the prototypical Mexican.

In the decades after the Mexican Revolution, politicians and intelligentsia, most notably the anthropologist Manuel Gamio, and writers like Octavio Paz, worked to construct a Mexican identity that was not tied to the Porfiriato’s European ideals but maintained an idealization of mestizos.[1] A new Mexican identity was born that assimilated Indigenous cultures into mainstream society through the project of indigenismo. This approach focused on Mexico’s pre-Hispanic history, idealizing Indigenous imagery while neglecting to incorporate modern Indigenous cultures and their social, political, and economic contributions. Indigenismo reproduced ideas of native “backwardness” and cultural stagnation, maintaining colonial race and class hierarchies. This cultural movement saw the incorporation, and one could argue, mass appropriation of Indigenous heritage into mainstream Mexican culture, particularly by the upper and middle classes. Gaytán argues that “the concepts of mestizaje and indigenismo were commonly used by government officials to encourage new Mexican nationalism rooted in the idea of racial homogeneity—la raza cósmica (cosmic race) that would allow mestizos to build a society based on the refined culture of Latin civilizations.”

Perhaps the figure that best represents indigenismo in relation to Mexican spirits is Mayahuel, the Aztec goddess of agave and fertility, who is closely associated in Indigenous imagery and texts with pulque. Mayahuel appears in various pre-Columbian texts which depict her as an agave plant with 400 breasts filled with pulque. Mayahuel is often invoked during tours of tequila distilleries and in industry books about tequila as the goddess of tequila—a figure that links the colonial beverage to Mexico’s Indigenous heritage, even though pre-Hispanic Indigenous communities did not drink tequila. Gaytán argues that like the Virgin de Guadalupe, Mayahuel functions as a spiritual home for the constructed Mexican nation—proof of tequila’s (and Mexico’s) ties to an Indigenous origin.

Mayahuel from the Fejérváry-Mayer Codex. Taken from Gaytán, “¡Tequila! Distilling The Spirit of Mexico.”

Decolonize Your Drink

Chef Mateo Herrera is part of a new generation of Indigenous chefs and food sovereignty activists, like James Beard Award-winner Sean Sherman, educating the public about Indigenous food practices and resisting food systems that perpetuate harm against their communities. His critiques of Sotol Raramuri challenge the ongoing ideology of indigenismo that connects colonial spirits to Indigenous spirituality and native Mexican identities.

“When I saw that post, it was a testament to how disconnected we are,” Herrera tells Latina. “People who are supposed to be supporting our culture, and embracing our culture, and promoting our culture, are also exploiting our culture. Especially when it comes to somebody marketing our culture as sacred. That’s very powerful. You’re not just offending people, human beings, but you’re insulting a culture as a whole. Our ancestors. It’s an insult to everything when you’re calling something sacred and it’s not.”

Sotol Raramuri is not an Indigenous-run distillery. Based in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, the brand is named after the Raramuri, also known as Tarahumara, people who are from the highlands and forests of Northern Mexico’s Cierra Madre. The Raramuri people’s indigenous drink is tesüino, or tescuini in Nahuatl, a kind of beer made from fermented maiz and drunk primarily during festivals and ceremonies. In Sotol Raramuri’s advertising on Instagram, images are used without attribution and it is not clear if all of the images are in fact of Raramuri people. Sotol is described as an ancestral elixir and sacred drink consumed during rituals, which is inaccurate and an attempt to sell their product via indigenismo and link sotol, a colonial invention, to Mexico’s Indigenous past. This form of colonial advertising neglects to recognize the existence of modern Raramuri communities and their contributions, for example, the battle against the deforestation of the Cierra Madre which has led to the high-profile murders of Raramuri activists and leaders.

For Mateo Herrera, the celebration of colonial spirits like tequila, mezcal, and sotol in Mexican culture and as Indigenous culture is also problematic given the experiences of Native Americans and other Indigenous communities with alcoholism. This is also the reason why he is critical of the popular tequila brand Pancho Villa Tequila, which uses the figure of the infamous Mexican Revolutionary leader, but who was, in fact, an alcohol prohibitionist. Villa famously outlawed alcohol in his home state of Chihuahua because of his concern with alcoholism in Mexico.

Herrera’s own work is grounded in the idea of being a steward of the land—someone who cares for the land regardless of ownership. A couple years ago, he transitioned from being a restaurant chef to a community educator and pop-up chef who works with ingredients that are indigenous to the El Paso del Norte area of West Texas and New Mexico. He works with museums, schools, and community-based organizations in El Paso and Las Cruces to teach classes on ancestral foodways in order to reconnect the community to sustainable, Indigenous food practices, which he believes are at the core of the area’s cultural identity.

“These medicines and plants that were once sacred to us have been turned against us,” Herrera says as he describes the effects of distilled spirits on Native American and Mexican communities. He says the same is true of corn which has been at the center of discussions around GMOs, food sovereignty in Mexico and the United States, and the prevalence of corn syrup in the North American diet.[2] We’re all people of maiz,” says Herrera. “We’ve all shared in her cultivation and keeping her alive. We share the same foods, and we share the same grains. We’re in harmony.”

To learn more about Chef Mateo Herrera’s work, visit his Instagram.

[1] In an article for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Mexican Anthropologist Federico Navarrete discusses this history further and describes what he calls the “Myth of Mestizaje.”

[2] To learn more about the corn industry in the US and Mexico see “Eating NAFTA: Trade, Food Policies, and the Destruction of Mexico” by Alyshia Gálvez.