While there has been a growing teacher shortage in the United States for a couple years already, the pandemic accelerated and aggravated this trend. A recent investigation by ABC News found that more than three quarters of states are facing teacher shortages, especially for specialized roles like special education and STEM.

One overlooked group of specialized teachers are bilingual educators who are capable of teaching in Spanish and English. Unfortunately, there is no aggregated data on the number of bilingual educators nationwide but advocates told Axios that the teacher shortage crisis is particularly affecting bilingual education.

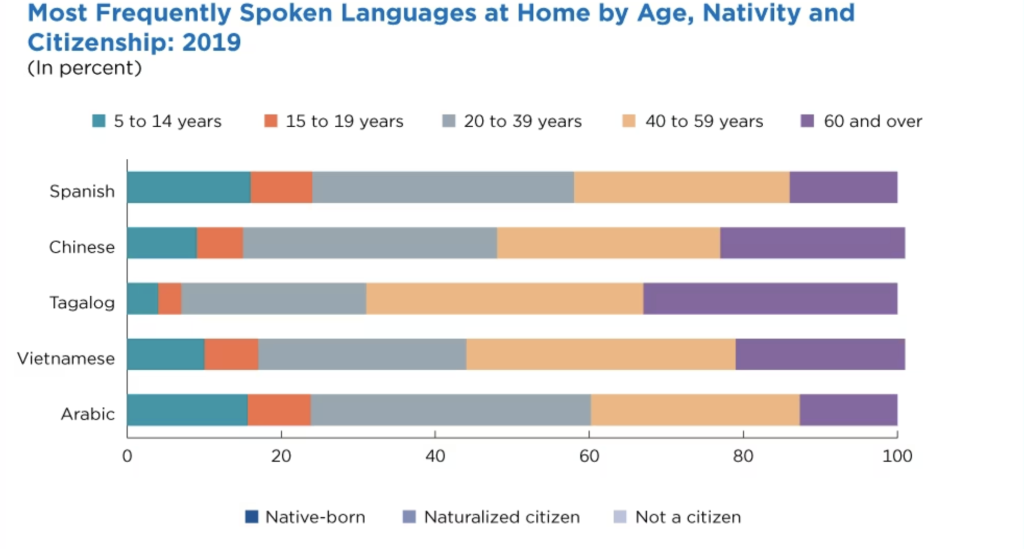

According to a 2019 U.S. Census report, 62% of households in the United States speak Spanish, making it the most spoken non-English language in the country. Out of those Spanish speakers, 16% are between the ages of 5 and 14, which, along with Arabic, is the greatest share of young speakers of any non-English language. The numbers speak for themselves and emphasize the importance of providing bilingual education in schools across the nation.

Source: US Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey, 1-year estimates.

“When I was in elementary school, specifically kindergarten, I didn’t know any English. So I remember it was very hard for me, just trying to communicate with my teachers, and even my classmates,” English-learner aide Elizabeth Alonzo told EducationWeek. As an immigrant who came to the U.S. in middle school without knowing English, she understands the importance of supporting students in their native language. “I picture myself in a classroom with bilingual students, but not only bilingual students, just a diverse classroom, and I just picture myself there, helping my students feel more comfortable around me, and being able to speak to me, even if they don’t speak English.”

While there are many educators who would like to specialize in dual-language education, the pathway to do so can be very tedious. In many states, on top of having a teaching license, bilingual educators must undergo additional schooling and bureaucratic procedures to be licensed to provide bilingual education. The University of Wisconsin-Madison announced in July 2022 a new one-year program which hopes to turn more Spanish-proficient teachers into certified bilingual and bicultural educators. “We really don’t do enough as an education system, as a state, as a society, to promote bilingualism and biculturalism through our educational institutions,” Pacheco said in a statement by UW-Madison. “…There are lots and lots of bilingual, bicultural people in the state of Wisconsin. We just don’t create incentives or pathways for them to become certified as bilingual teachers.”

In addition to the difficulties to even get certified for the job, the role itself is demanding and poorly compensated. “Bilingual educators are facing a lot more demands, what we call the invisible tax,” Feliza Ortiz-Licon, Chief Policy and Advocacy Officer at Latinos for Education, told Axios. Bilingual teachers often end up doing translation outside of their work duties without additional compensation for their skills and time.

Although there may not be a nationwide strategy to overcome the challenges of training, recruiting and maintaining bilingual educators, it should be a priority. Improving access to equitable education is the starting point to making sure English learners have a fair shot at finding success in the United States. Sheiveh Jones, executive director of Human Resources at San Diego County Office of Education, told KPBS that setting up bilingual teachers for success is the first step. “It’s good for students to see that their teachers might be second language learners or educators of color because now they can see themselves in their teacher.”