Since the late 1970s, genderqueer artist, filmmaker, performer, and curator Vaginal Davis has indelibly shaped the underground art and music scenes through “low-cost, high impact” genres of club performances, queer zines, and experimental film and video productions. Through her art, Davis has sought to disrupt and question the social norms of straight and queer culture. Through the 1980s and early ‘90s, Davis led the Queercore zine movement with her self-published Fertile La Toyah Jackson Magazine, which both chronicled and inspired the queer underground. “With my writing in queer zines and independent publications I acted as if the queercore movement was this huge vibrant scene when in actuality it was quite small, but in pretending to be a larger movement it actually activated its growth internationally,” Davis explained to Hyperallergic.

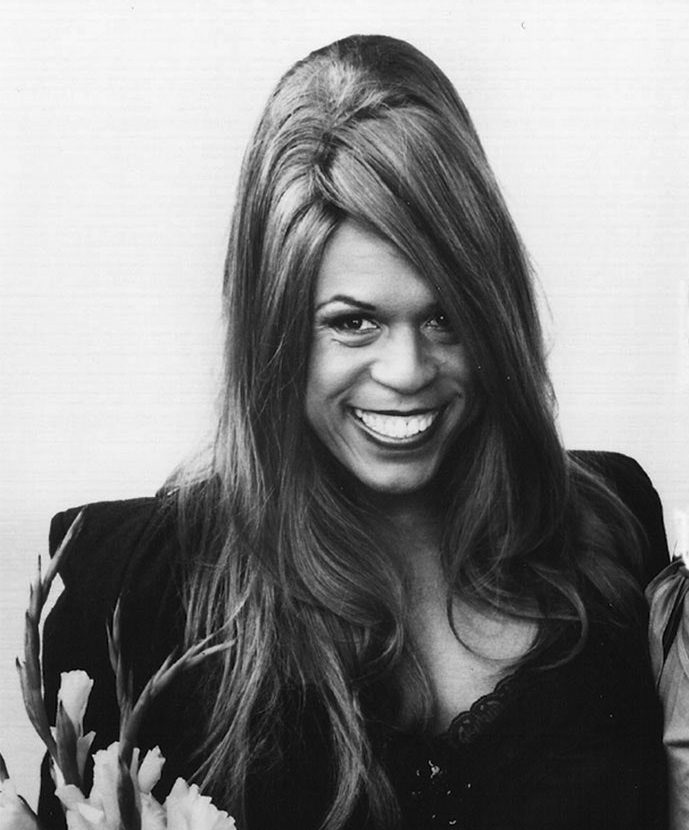

Source: Pastelgram.

An artistic provocateur since she first began performing in drag as a teen in the ‘70s, Davis has explained in several interviews that she “was always too gay for the punks and too punk for the gays.” Finding her art illegible within the conventions of LA’s underground scene, Davis adopted alternative language to describe her radical outsider art, describing herself as a “social threat,” a “sexual repulsive,” and — eventually inspired by Cuban American queer theorist Jose Esteban Muñoz — a “drag terrorist.”

“I couldn’t perform in many gay clubs because I wasn’t doing a spin on a popular Black singing diva like Donna Summer or Diana Ross,” Davis explained to curators at Studio Museum Harlem. “If you were a Black drag queen, you took on a persona like the “Grace Jones drag queen,” and I was writing my own songs and lip-synching. I was basing my persona on Angela Davis, the radical Black feminist.”

“When Angela Davis was the most wanted woman in America, I was just fixated with that image of her,” Davis described in a 2015 lecture at NYU. “By the late ’70s, I had decided I sort of wanted to sexualize her name and become her, more or less. So, I started in the late ’70s calling myself Vaginal Davis. I started to perform– or tried to perform– at these gay clubs in Los Angeles, in Hollywood. The people in these clubs, they would look at me and say, ‘Vaginal Davis? Well who are you supposed to be?’ And I said, ‘Well, Angela Davis– it’s a homage to that.’ And they’d say, ‘Well who’s that?’ They didn’t know who Angela Davis was.”

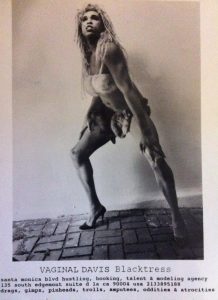

Source: https://scaaic.org/event/vaginal-davis/

Since she refined the Vaginal Davis character in the punk band Afro Sisters, Davis has developed several other personas in various conceptual bands. These many characters include a Chicana teenage singer named Graciela in the band ¡Cholita!; The Female Menudo, a white-supremacist “complete with ZZ Top beard,” known as Clarence in the thrash band Pedro, Muriel, & Esther; and Rayvn Cymone McFarlane in the band Black Fag. Davis explained in conversation with Rose Salseda, assistant professor of art and art history at Stanford University, that the character of Graciela was inspired by the “amazing sassy styles and defiance” of “Latina teens.” The character allowed Davis both to explore her own “Latin roots” and love of Spanish-language pop music and to present her “politics in a humorous fashion without being dogmatic, to show that women’s humour is playful and whismical.” Through these hyperbolic characters, Davis deployed exaggerated forms of self-invention to challenge and destabilize entrenched notions of racial and gender stereotypes. In spite of the numerous characters that Davis has adopted over her decades-spanning artistic career, “Vaginal Davis” remains her primary nom de guerre.

Although her adopted name pays homage to the iconic black radical, Vaginal Davis has long cited her own mother as the ultimate inspiration for her artistic life. “I’m so intertwined with my mother,” Davis explained in 2015. “My whole career as an artist, and all of my visual art, is basically co-opting my mother. My mother didn’t consider herself an artist, she just made stuff. Looking back to the things that she did, they were installations, assemblages– things in the art world that have proper names to them– she was doing this way back then. If I get any notice for any of my art works or any of my performances, it’s because I just copied my mother.”

Davis described her mother as a Black creole “femme lesbian separatist” from Louisiana who conceived Davis with a Mexican-American man she met at a Ray Charles concert, at the Hollywood Palladium. Growing up in South Central Los Angeles, Davis’s politics were shaped by her mother, a staunch feminist community activist who, according to Davis, “would plant food on the vacant lots for the whole community– all the Latinos, all the blacks, anyone who needed food.”

Davis has also cited the Black Panthers, who organized in South Central during her childhood, as important role models for her radical approach to performance: “When I was growing up, a little girl in South Central Los Angeles, the Black Panthers basically took over the education system. They came into the schools, they had guns, and they took over. They were teaching us all these revolutionary songs and chants and what not.”

Beginning in the 1980s, Davis began performing at queer punk venues in New York City, including the legendary Pyramid Club, where a “politically conscious drag performance art” scene was being developed by drag performers, including RuPaul, Lady Bunny, and Lypsinka. In 1987, Davis performed for the first time with RuPaul and queer “cowpunk” musician Glen Meadmore.

Through the 1990s, Davis continued to perform on stage and produce experimental videos. These included two VHS volumes of the Fertile La Toyah Jackson zine and The White to be Angry, a 1999 visual album by Davis’s band Pedro, Muriel & Esther that confronted white supremacist extremism and skinhead culture.

In a 2020 interview with them., Davis effectively summed up her career when she explained the conceptual divisions between “gay” and “queer” culture that have motivated her art:

“There is a difference between gay and queerness, between heteronormative-type gay people and people who are queer and live a real queer life. Being queer isn’t just sexuality. Queer to me means not wanting to fit in anywhere. It’s relishing in your outsider status as a misfit, weirdo, freakazoid. Always being suspect, perverse, maladjusted. It’s not about the mechanism, the nuts and bolts of sexuality. It’s more about the aesthetic drive as the principled guideline.”