In Janicza Bravo’s world, a Lynch-esque reality exists on a “planet just next to ours.” Among her many characters, we see a frantic blond woman who loses her phone and spirals into a dark hole of suicidal depression and paranoia on the day of her birthday; a racist, paraplegic young white man who self-immolates after three failed dates in one night; and a traveling knife salesman who gets his toe sucked by one of his potential clients while an older woman watches. In this bleak, surreal world where Bravo’s films live, there’s a lingering sense of unease. Something just doesn’t seem quite… right.

Bravo’s work lives in an absurdist cosmos. She navigates nightmarish, discomforting themes by injecting humor into her work with a touch of theatrical lunacy. So it only made sense that Bravo would direct Zola — based on the 2015 Twitter-thread thotessy of viral fame.

“What is most [recurrent] in my work is a search for belonging. Central figures refusing to go unnoticed in a world not built for them,” Bravo tells Latina. Born in Brooklyn and raised in Panama until the age of 12, Bravo grew up traveling back and forth between Panama and the U.S. until her family settled in New York. She expresses a sense of ongoing displacement in her earlier years — not feeling welcomed or included in Latin spaces. After spending her adolescence in the U.S., she began to see herself as Black first.

Later, as she entered adulthood, she knew she wanted a career around performance, maybe theater, maybe film. Bravo attended Playwrights Horizons Theater School at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. At that moment in her life, she didn’t know, or even believe it a possibility, that she would become a director — there were not yet many examples of people who looked like her in that role. Not until her freshman year directing teacher told her she could be a director did she begin to explore that route. Her first short film Eat (2011), debuted at the South by Southwest Film Festival and starred Katherine Waterston and Brett Gelman. Eat caught the attention of Michael Cera, who starred in Bravo’s second short Gregory Go Boom (2013), her noir short Man Rots From the Head (2016) and later in her first independent film, Lemon (2017). It wasn’t long before she had her eyes set on what would be her most high-profile film yet.

After Aziah “Zola” King posted her epic 148-tweet tale about a ‘hoe trip’ gone bad, Bravo knew she had to be the one to tell the story. Bravo connected with Zola’s voice. “When I read her thread, I thought, ‘oh, this is me, this is how I would navigate through this, and this is how I would process and exercise it,’” says Bravo. “I would rewrite the narrative, I would make myself the straight man in a world where everyone else was coming undone.”

In the Zola saga, King wields her own sense of humor to cope with traumatic experiences involving deceit, sex trafficking and murder. With Bravo’s mastery of awkward blocking, eerie sound design, and unsettling wide shots, King’s suspenseful yet comical story has come to life. The Shakespearean tale of a 20-year-old stripper who lived it to tell it now resides in Bravo’s provocative oeuvre.

Dilcia Barrera, Film Programmer for the Sundance Film Festival, met Bravo in 2014, the year Gregory Go Boom won the Grand Jury Prize. Barrera sat down with Bravo for Latina to chat about the brilliant Panamanian-American director’s unconventional path to becoming a filmmaker, her personal connection to Zola, and what her born-again Christian parents think about her work. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

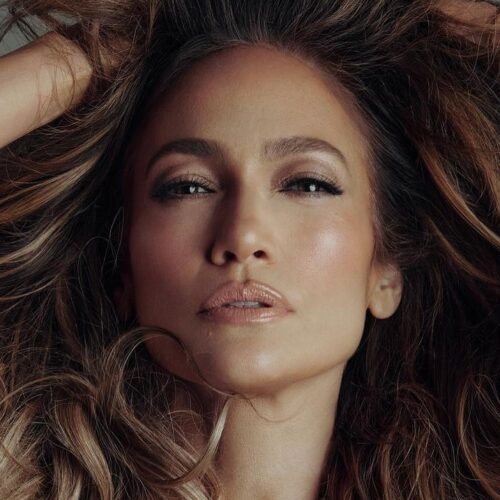

Photography by Robert Ascroft.

Dilcia Barrera: The journey of this film is not “traditional,” but also getting to this moment in your career has been all but traditional.

Janicza Bravo: I’ve said some version of this before, but I didn’t know I was a director until someone told me that I was. And what I mean by that [is], at this moment, I feel I am inherently a director. But I didn’t know when I was 17 or 18. And if you get to go to college, or if you want to go to college, and you’re making a decision about what you believe your career path is going to be, I didn’t know that that was an option for me. I hadn’t had an example of myself that I could look to where I felt I saw myself. But I had wanted to be in film, I wanted to be in theater, I wanted to be in performance. And I felt I could be an actor, [afterall] there was Whoopi Goldberg. So that seemed like that was an option for me. I know that seems sort of goofy. But I do think that that’s a little bit of how I feel my brain was just literally that simple. Where you see yourself, it means that’s where you’re allowed to be.

DB: Who told you that you are a director?

JB: My freshman year directing teacher, his name is Fritzerel. I give him special thanks in everything I do.

DB: I have a very clear memory of when I met you, because we met at Sundance in 2014. You were there presenting Gregory Go Boom. And so you were there, it was an exciting moment, but I’ll never forget your face when you won the Grand Jury Prize. You really did not believe what was happening. Why couldn’t you believe that? What was going through your head?

JB: I think that when we got into Sundance, [first of all] I didn’t think Sundance would accept the film, because most festivals wouldn’t accept a film that had been online. And so it was already a win that Sundance had said yes. That was my dream. It was on the list of the places every filmmaker wants their movies to play. I think when I won [the Grand Jury Prize], it just didn’t make sense. I do think that I loved the movie, and I thought it was special or whatever. But I just couldn’t believe that. It meant that it wasn’t just me that believed in myself. Right? It wasn’t just Brett, it wasn’t just Michael, it somehow meant that what had been a very small pocket of people was starting to open up. And I think that shock, you probably saw my face was also kind of a combination of fear, but also this great big joy that I wasn’t sure that I deserved [the award] falling into my lap.

DB: I keep thinking about the anticipation of your second film. A lot of people don’t know that oftentimes filmmakers’ second films become the most difficult to develop or get produced, and it’s especially much harder for people of color and women.

JB: I had, at this point, been working in television a little bit. And, the more I worked in TV, for me, not only was there financial security that came with it, which was a huge win. It meant that for every person I sat in front of and basically was asking them to trust me, I had a longer list of people that believed in me. Or a longer list of people that I could use as your calling card. I’ve worked for FX or I’ve worked for HBO, I’ve worked for Netflix, you know, Magnolia bought the movie, basically, you’re just throwing around brand names, even if it doesn’t mean anything, but that there is some value there. A lot of these places, a lot of these creators had said yes to a woman who was non-white, and also Latin. What was clear to me was that the road to making Lemon, my first film, was a long one. [But] getting to my second [film], it just wasn’t gonna be that [hard].

DB: That’s amazing. I love that.

JB: I mean, it took years. We’re here four years later, it still took years.

DB: So yes, definitely a long track. But there was something in Zola that made you want to do it and what was the biggest attraction to that story?

JB: It was the real Zola’s voice, A’Ziah King. Her voice kind of woke me up. The piece, the original Twitter thread, came out in October of 2015. Without citing any specifics, this is the year in which there had been a multitude of Black people who had been slain by the cops oftentimes unarmed and it was a year that followed years and years and years of this narrative. This story kind of blossoms 10 months into what is a pretty bleak premise in this country, in America, for non-white people. The humor, and the life that she had injected into this story; it was so electric. I’d never read anything like it. To me it was synonymous with this great piece of literature. I felt like I’m the best person to tell this. I am the best person to protect it. The way I think it is special and the way that I think it is important, I don’t know that other people will see it that way.

DB: Zola is based on a real story. It’s not your story. But it’s not not your story. How much did you pull from your own story, Janicza’s story?

JB: I think that it is very much not my story. I did not live it. I did not go on this road trip from Detroit to Florida, I was not seduced by a white woman and potentially sold into some kind of sex slavery. But it is my story. And it is many people’s story who are like me in that, if you are living in a body where people treat you as if you are invisible, if people have decided that you are voiceless, you become a kind of invisible person in the world. And so what I took for myself was that to me, I am Zola. And I injected her with my sensibility. That is my sense of humor, the way I look at the world, the way I look at whiteness, the way I look at myself in a space where I’m not being considered.

DB: I keep thinking about what you’re saying about injecting a sense of humor in the story. You like to make fun of things and people in situations, especially when these situations are uncomfortable, and especially with situations that people don’t want to make fun of. In the case of Zola, this movie about trauma and survival, you said it in a fun thriller comedy road trip adventure so effortlessly. I think you’re a master of creating this fine line. That seems to come to you naturally.

JB: I’m sure that has a lot to do with how I was raised. And probably that I am an only child. I grew up in Panama and then I moved to the U.S. when I was 12. And I’ve lived in America for a very long time and I have seen a lot that didn’t always feel good. I’ve been in a multitude of situations that caused me great distress and the way that I…my superpower if you will, is my wit, is my quickness. If I didn’t have that, how would I get through it right? I think my sensibility that comes across on a platform like Instagram is me laughing or me laughing or inviting people to laugh at the things that we kind of want to move through, or the things that are a bit uncomfortable that don’t exactly feel good. I like sitting on the things that don’t feel good.

DB: As you know, I’m a daughter of immigrants and they have no idea what I do. Do your parents? Have they acknowledged what you do? And did they see the movie?

JB: They did go to the premiere of Zola in New York and Fort Greene Park. I have to also say my parents are born-again Christians and the movie is in their eyes, deeply satanic. It is of the devil. It’s the devil’s work, right? So, I kind of knew that it might not go well, but also felt we were in an environment that I felt was going to support me. At the end of the movie, they had said very little. [First], my dad had said it was pretty and that he was proud of me. [Then] my mother said, “I don’t know, I don’t know I don’t know,” thrice, it felt great. Then we rode in a car together. They started talking about someone’s baby, church, and someone’s funeral and literally, I was upset. I felt really alone. It’s such a vulnerable moment and I’m my mother’s only child and I felt really sad. But then we went to this party for the movie. I had 16 members of my family there, half siblings, cousins, nieces, nephews, and a lot of people singled out my parents and told them that I was special, or I was amazing, or I was great. And I saw them change. I think there was a little bit of intimidation around what this “thing” is, and that there isn’t exactly a language for what it is for them. They don’t know how to translate what I’m doing to their friends. So there was a real win [that night] because all of these people told them I was special. Then I think they understood that they were special too.